[ad_1]

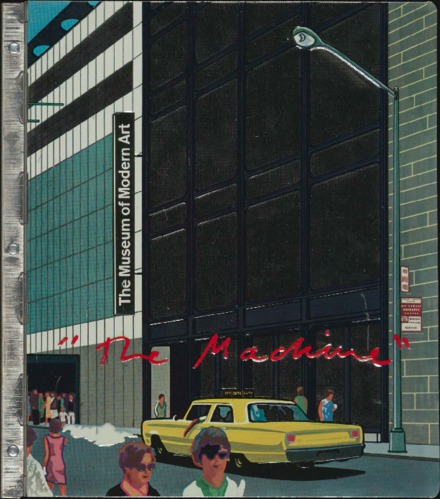

The catalogue for the exhibition “The Machine as Seen at the End of the Mechanical Age.”

COURTESY MUSEUM OF MODERN ART

When a show about art and machines opened at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1968, it seemed like just another wide-ranging survey exhibition about the role of technology. Then an artist pulled his work from the show, altering the course of art history.

It all began with a disagreement that had nothing to do with the show’s theme. Curated by Pontus Hultén, then director of the Moderna Museet in Stockholm, “The Machine as Seen at the End of the Mechanical Age” was hardly controversial. It featured an array of works about or relating to the machine age, from as far back as Leonardo da Vinci’s day up through experimental pieces by modernist avant-garde artists. But the Greek artist known simply as Takis had a beef with the show: he claimed that the institution had not consulted him about including his 1960 sculpture Tele-Machine, which made use of magnets and gadgetry that caused objects to move as if on their own. On a chilly winter day in January 1969, Takis and a group of supporters marched into MoMA, picked up his sculpture and, before museum guards could take action, carried the work downstairs to MoMA’s sculpture garden.

These days, artists demanding the removal of their works from exhibitions is a common tool in the arsenal of political protest. In the cases of both the Aichi Triennale and the Whitney Biennial, artists called for their works to be pulled amid protests over circumstances at those institutions. But in 1969, this was something novel.

Takis’s fellow demonstrators sat around the object and refused to move until Takis was allowed to speak to MoMA’s director at the time, Bates Lowry. The two men spoke for about an hour, and then Takis brought the group some news: the sculpture, which had been gifted to MoMA by patrons John and Dominique de Menil, would be taken off view.

Did MoMA have the right to display Takis’s work without informing him? What could be done to stop the museum from doing something like this again? These questions caused what may otherwise have been a bizarre footnote in MoMA history to snowball into something much larger. Over the course of the following year, Takis joined forces with artist Hans Haacke, sculptor Carl Andre, critic John Perrault, and others to form what would eventually be called the Art Workers’ Coalition. The group would go on to protest a lack of transparency at art institutions and urge museums to acknowledge their role in political oppression around the world. Together, its members would organize a historic anti–Vietnam War art strike through which the Whitney Museum, the Jewish Museum, and other major New York institutions would close for the day. In the process, they offered some ways in which artists could reserve their rights and rebel against major museums.

In a New York Times report on Takis’s protest a photograph shows the artist, surrounded by onlookers, cradling his Tele-Machine. Takis told the Times he staged the removal “as a symbolic act to stimulate a more meaningful dialogue between museum directors, artists, and the public.” Takis died this past August at age 93. With our present times as proof, his action seems to have worked.

[ad_2]

Source link