[ad_1]

The software that emerged as “Presenter” more than thirty years ago, then became PowerPoint and its brethren, has transformed the way we teach and hold meetings and manage relationships and worship.¹ It has turned the vertical surfaces of our built world into substrates for an unending flow of dynamic, didactic messages. And for nearly as long as it has been in existence, slide presentation software has been under attack. In 2003, visualization shaman and statistician Edward Tufte critiqued the program for impoverishing the art of rhetoric, normalizing the slickly presented non sequitur, and condoning the proliferation of painful graphic design.

Since long before the computation age, teachers, businesspeople, and military officers have been deploying pithy reports, wall charts, flipcharts, overhead transparencies, 35mm slides, and chalk-, cork-, and whiteboards to make their points.² Yet PowerPoint, much like desktop publishing platforms including PageMaker and QuarkXPress, democratized the making of persuasive media, enabling junior sales associates and high-school juniors to add a sheen of professionalism and credibility to their reports by using standardized templates and tools. As the software evolved, it began to offer more cinematic and multimedia features: dissolves, fades, embedded video, spinning word art, and soundtracks. The arrival of Apple’s Keynote (2003), Google’s Slides (2007), and Prezi (2009) have only increased the possibilities for expression and distribution.³

Today, pitch decks filled with emotive stock photography and bold, sans-serif declarations—including Fyre Festival’s promise to “traverse the globe to find untouched lands, and convert them into unparalleled experiences”—are often all that stand between a team of ambitious, inexperienced entrepreneurs and millions of dollars in venture capital funding.4 One-page bullet-pointed security briefings are the sole means (or pretense) of orienting the US commander in chief. Recognizing the ubiquity and epistemic imperialism of the slide deck, many artists—including David Byrne, Tan Lin, Daniel Eatock, Timothy Evans, Michael Riedel, Linda Dong, Simon Denny, and Tony Cokes—have taken up the medium, adapting its modes of address to comment on contemporary managerialism, information labor, and media culture.

As Erica Robles-Anderson and Patrik Svensson argue in “One Damn Slide After Another,” analyzing and critiquing presentation software and the organizational culture surrounding it, as these artists do, reveals “the largely under-appreciated reliance on performative authority in knowledge production.” Slides “are not designed to provide audiences with evidence that speaks for itself”; they rely on “the orator’s talent . . . to create a sense that everything connects.”5 They’re props—boxes full of “content”—supporting a choreographed performance. But what happens when those slides are made to stand on their own—when they’re projected onto a gallery wall, played on a loop in an event space, or presented online—with no orator present to guide us? How does the slide deck function as a stand-alone medium, and what does it say about contemporary modes of communication?

Around the same time that Tufte launched his warning, in the early aughts, artist and musician David Byrne mined PowerPoint’s potential as an artistic medium. He told an interviewer in 2004:

I kind of love to use cliched phrases, and cut them loose from what they’re associated with, and use them as free-floating poetic elements that I can rearrange as if they’re blocks and make them mean something completely different or reveal them to be as absurd as they actually are.6

His presentations—packaged in a book and accompanying DVD (Envisioning Emotional Epistemological Information, 2003) with decks accompanied by original music—are filled with arrows pointing to nothing in particular, contentless speech bubbles, gratuitous word art, and charts that Byrne selected because they “make no sense whatsoever. The form immediately makes you think that it’s conveying information. . . . [Yet] the more you look at it, the more you realize [that] the content . . . is just confusing you further.” The slides evoke rhetorical acts of meaning-making, but they communicate little more than their own pointlessness. When promoting the book on tour, however, Byrne gave performance-lectures that layered entertaining ekphrasis atop the inscrutable slides.

More recently, the poet Tan Lin utilized PowerPoint for his “Bibliographic Soundtrack” (2012) and “The Ph.D. Sound” (2012), two slide-poems comprising collaged excerpts from social media, indexes, bibliographies, and other non-literary sources. The paradoxically soundless, forty-minute-long “Soundtrack” features texts, mostly white letters on a black background, in a variety of columnar layouts. The fifteen-minute “The Ph.D. Sound” stretches haphazardly formatted single-column bibliographic citations across vibrantly colored backgrounds, and sets them in motion against a soundtrack mixed by DJ Mosco.

Making full use of PowerPoint’s features, Lin experimented with the layout and length of texts; the juxtaposition of text sources and formats; the application of fades, wipes, and scrolls; and the layering of visuals and sound. As the artist explained to the poetry magazine Jacket2: “PPT allowed me to diffuse a book into a general operating system, in this case a specific and much maligned genre of office productivity software.”7 Rather than mimicking the rapidly advancing decks one might see at a tech or TED conference, Lin “wanted something slow, porous and meditational,” in order to produce the experience of “giv[ing] oneself over to something,” even if that “something” is a text designed for distracted reading.

Myriad contemporary filmmakers, composers, and other creators of time-based works have likewise created durational pieces that ask the audience for viewing stamina. This work typically offers commentary on a culture whose temporality is characterized by the instantaneous status update, the quick refresh, the scrolling feed, the 30-second TikTok video, the PechaKucha—the last, a mode of presentation in which the slides auto-advance every 20 seconds, compelling presenters to perform at the program’s pace. Lin goes for the slow reveal, the painfully gradual fade, and he invites us to surrender ourselves to the performance, while also accepting our likely failure to commit. “We’d like you to keep your phones on for this,” he directed his audience at a 2014 screening at Harvard, granting us time and permission to peek at our text messages and status updates between fades and pans.

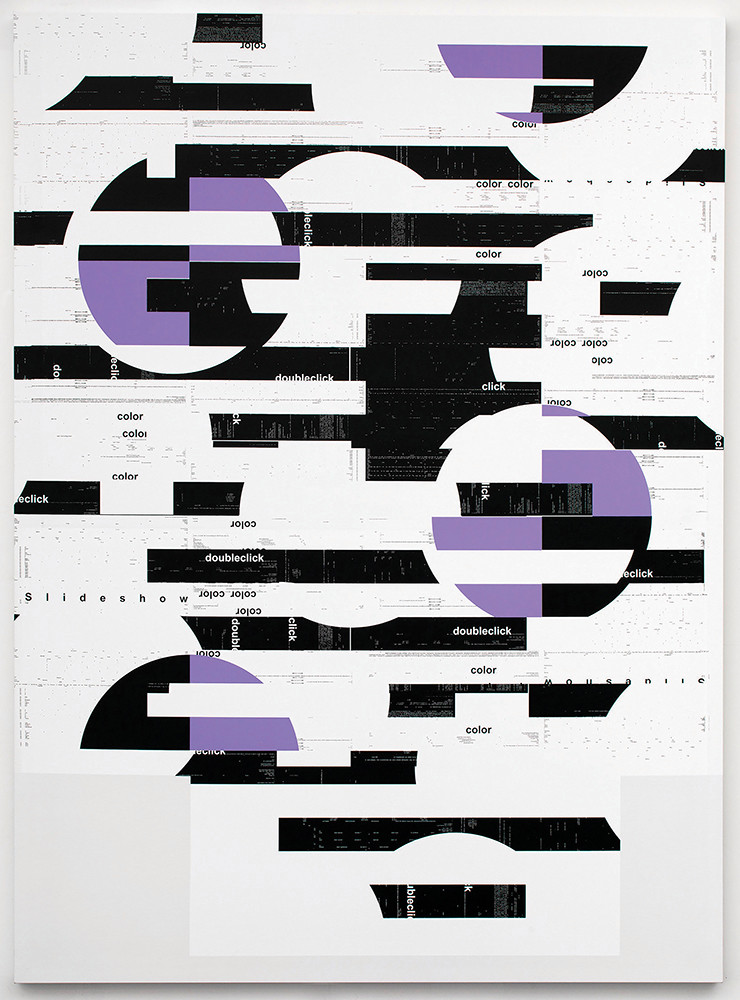

For Daniel Eatock and Timothy Evans, the reveals and fades themselves are the point. In their three-minute video “Transition” (2007), the artists’ creative palette consists of, well, PowerPoint’s transitions, rendered in black and white: the morphs, drapes, pushes, splits, cuts, curtains, fractures, shreds, ripples, ferris wheels, and orbits that stylize the shifts from one slide to the next—and thereby imply particular rhetorical shifts. The curtains effect—wherein the image onscreen softens into fabric, then pulls and sways toward the left and right margins, revealing the next slide—likely signifies a reveal, for instance, while a fade proposes a more gradual evolution. A fracture—wherein the screen-image shatters into dozens of pointy shards, which then fall to the bottom, making way for the next slide—implies an intentional, even violent negation or contradiction or counterpoint, whereas the peel-off—in which an invisible hand grasps the screen-image at its bottom-right corner and carefully peels it away, like a post-it note, toward the top-left corner—proposes that the second slide is merely an iteration or progression from the first. Working in a similar vein, Michael Riedel’s “PowerPoint” paintings (2011–) freeze the glitchy transitions between two slides, which are then materialized as large-scale silkscreens on linen, while designer Linda Dong’s video Keynote Motion Graphic Experiment (2015) mobilizes Keynote’s basic animations to create action sequences for geometric figures.

Photo Jens Ziehe.

While much of this work exploits PowerPoint’s formal and interactive qualities—its relentlessly linear sequence of slides, the affective and semantic dimensions of its transitions and animations, its charts and graphs—other PPT artists use the signature slide aesthetics of particular institutions or industries as fodder for their creations in other media. The aesthetics of management and military culture are an endless fount of inspiration for Berlin-based artist Simon Denny, who has appropriated the visual iconography and graphic style of US National Security Administration slides leaked by Edward Snowden in 2013. As I’ve noted elsewhere, Denny found that the graphic and verbal style of these documents, while chaotic and gaudy, revealed subtle political discernment: slight variations signaled different degrees of confidentiality.8 Denny commissioned David Darchicourt, former NSA creative director and exhibition designer for the National Cryptologic Museum, to create new illustrations of screaming eagles and turtles in soldier uniforms—which art critic Chris Kraus describes as “heavy metal-infused gamer-cartooning”—for his New Zealand pavilion exhibition, “Secret Power,” at the 2015 Venice Biennale.9

But what made Denny’s PPT-inspired posters especially potent was their performance in context: they were displayed in glass-fronted, LED-lit racks of servers—technological “black boxes”-turned-vitrines—in the sixteenth-century Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana, a Renaissance marvel on Venice’s Piazza San Marco. In a monumental building that houses many of the early modern era’s great maps and printed books, as well as numerous pre-print forms, Denny positioned these PowerPoint slides as today’s electronically illuminated manuscripts, network diagrams as our contemporary portolan charts, and hackers as the new merchant-explorers. Visitors are left to wonder: are bureaucratic communications and security intelligence—with all their garish graphics and charmless prose—the apotheosis of the Renaissance’s pursuit of enlightenment, a pursuit embodied by the library and all that it safeguards?

American artist Tony Cokes combines a political sensibility akin to Denny’s, with a facility for textual appropriation and sonic attunement like Lin’s. For four decades, he has mined texts from newspapers and magazines, advertising, government documents, activist manifestos, and theoretical treatises. He describes many of his finds, because of their banality or ubiquity, as “hidden in plain sight.”10 Cokes pairs those passages with incongruous rock, pop, industrial, punk, and rap music, and edits the elements together into minimalist newsreel-style videos or slide shows. In his “Evil” series (2003–), he examines post-9/11 politics and media through, Cokes says, “a series of small ‘case studies’ framed around a particular article . . . that get[s] excerpted, sequenced, composed, and juxtaposed.” The “Evil” videos scroll through chopped-up texts set in default corporate typefaces (usually Helvetica and Times New Roman) and laid atop monochromatic backgrounds, some of which allude to the Department of Homeland Security’s color-coded alert system. Cokes swipes and fades from one excerpt to the next at a moderate pace, which sometimes syncs and other times clashes with the accompanying soundtrack. These mismatches, he suggests, productively “deform” the text, complicating our reading.11

Across the series, small references amalgamate into extended commentary on foundational social structures and historical legacies, like capitalism, racism, and the institutions and conventions through which we create and uphold public truths. Evil.27: Selma (2011), quoting a text from the creative collective Our Literal Speed, reminds us that “the American Civil Rights Movement took hold in a society moving from radio to television—from a social collectivity dependent on imagination to one where everything is instantly visible.”12

We’ve now cultivated a mediascape in which everything can be faked or hacked, and public truths seem not only impossible but also undesirable. In this context, Cokes takes texts that are “hidden in plain sight” and positions them on a slide platform that is itself, because of its mundane ubiquity, likewise often hidden. He adds color, typographic formatting, and sound, which both give form to and deform those news articles, government reports, Kanye West lyrics, and passages from theoretical treatises. Cokes, like Lin and Byrne, renders sampled texts newly visible, projected in the efficient, urgent, and didactic visual language of subway signs and quarterly reports. Their substrate, the humble slide deck, ultimately shows itself and its secret rhetorical power, too. Its wipes and fades reveal the performativity of rhetoric in an age of PowerPointed persuasion.

1 I’m grateful to the many generous folks on Twitter who contributed slide-art examples for use in the undergraduate Tools class I taught in the fall of 2019. See tools.wordsinspace.net

2 See JoAnn Yates, Control Through Communication: The Rise of System in American Management, Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1993.

3 In 2007, Google released a presentation program for Google Suite; it was relaunched as Slides in 2012.

4 Josh King, “Fyre Festival—The Pitch Deck,” SlideShare, Feb. 1, 2019, slideshare.net.

5 Erica Robles-Anderson and Patrik Svensson, “One Damn Slide After Another: PowerPoint at Every Occasion for Speech,” Computational Culture, 5, Jan. 15, 2016, computationalculture.net.

6 David Byrne, “David Byrne’s PowerPoint Art,” interview with Debra Schifrin, “Day to Day,” NPR, Jan. 14, 2004, npr.org.

7 Tan Lin interviewed by Kristen Gallagher, “Why Power Point?” Jacket2, Jan. 23, 2013, jacket2.org.

8 Shannon Mattern, “Furnishing Intelligence,” Perspecta, 51, 2018, pp. 299–314.

9 Chris Kraus, “Here Begins the Dark Sea,” in Simon Denny, Secret Power, Milan, Mousse Publishing, 2015, p. 23.

10 Jenelle Troxell, “Torture, Terrror, Digitality: A Conversation with Tony Cokes,” Afterimage 43, no. 3, 2015, p. 20.

11 Ibid.

12 Our Literal Speed, “About,” ourliteralspeed.com, accessed Nov. 14, 2019.

This article appears under the title “Auto-Advance: The Art of the Slide Deck” in the February 2020 issue, pp. 64–69.

[ad_2]

Source link