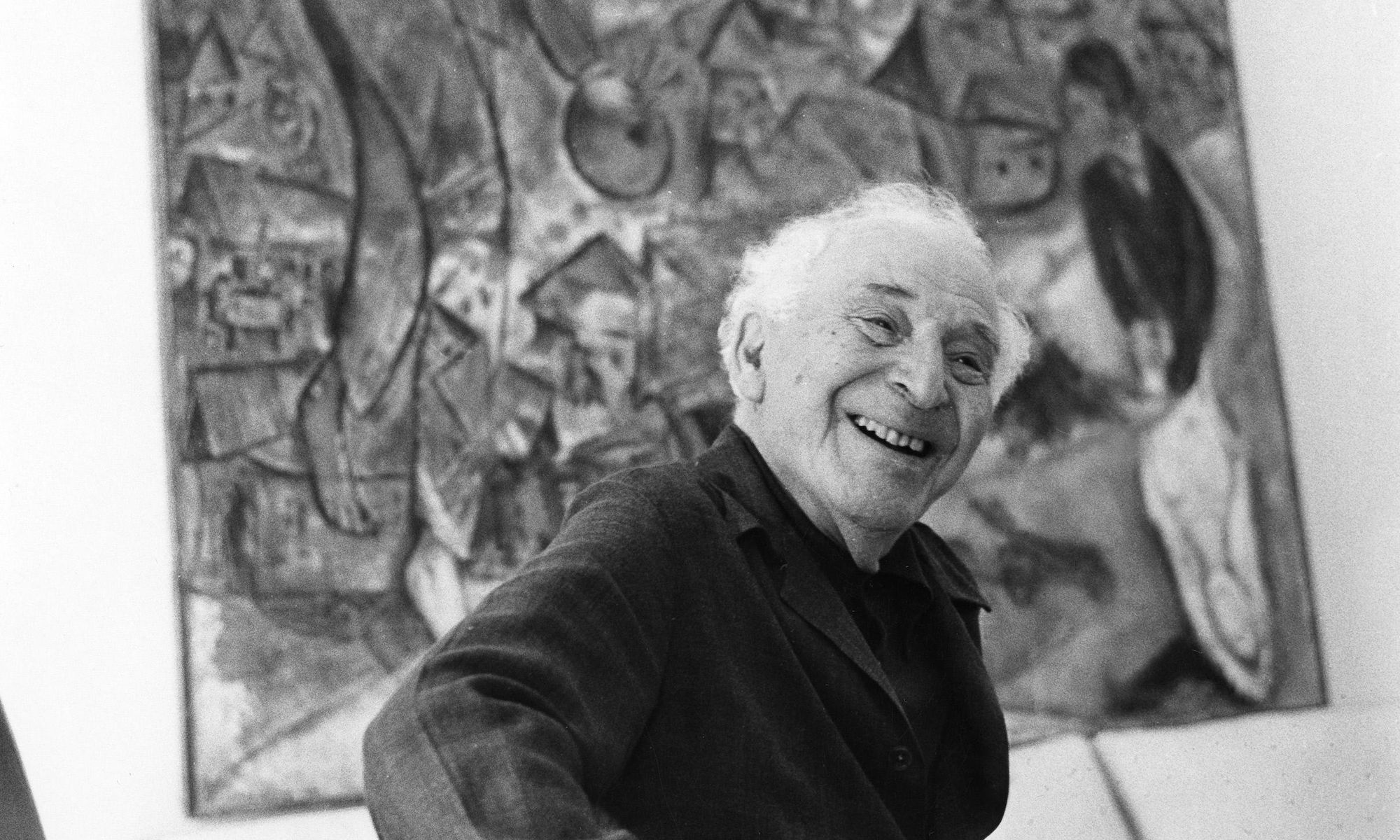

Marc Chagall in the living room of his home in Saint-Paul de Vence in France, 1977 Photo: Granger – Historical Picture Archive / Alamy Stock Photo

The Mondex Corporation, a Toronto-based firm dedicated to the return of art looted during the Holocaust, has settled a lawsuit with a former client over fees for the restitution of a $24m Marc Chagall painting that for decades hung in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York.

Mondex investigates works of art that may have been seized by Nazis or sold under duress during the Second World War. It searches for potential heirs and helps them make restitution claims on the works in exchange for a cut from their eventual sale. The firm, founded in 1993, claims a 97% success rate and has been a driving force behind many restitution cases over the past several decades.

In April 2020, Mondex negotiated the return of Chagall’s Over Vitebsk (1914) from MoMA to seven heirs of shareholders of Galerie Matthiesen, the Berlin gallery that owned the painting when the Nazi Party came to power. The painting had been in MoMa’s collection since around 1949. In the deal struck by Mondex, the heirs would pay $4m to the museum in exchange for the work. The cash would be used to create the Franz Matthiesen Fund, named for the gallery’s founder—also known as Francis—and dedicated to Nazi-era provenance research for the next 25 years.

“You have a case which is not black and white,” Mondex founder James Palmer told The New York Times earlier this year, of the heirs paying the museum for the painting to be returned. “It makes perfect sense given some of the questions that can’t be resolved.”

But in February 2021, Mondex filed a lawsuit in the Ontario Superior Court of Justice against Franz’s son, Patrick Matthiesen, for allegedly not following through on the deal. In the filing, Mondex claimed damages of around $8.5m.

Matthiesen, an art dealer with a gallery in London, referred to Mondex’s fees in a November 2022 affidavit as “exorbitant”. In a counterclaim, Matthiesen accused the firm of breaching contract, negotiating with other parties behind his back and hiding critical information in ensuing legal filings. Mondex’s lawsuit and Matthiesen’s countersuit were resolved in April of this year in a private settlement, though documents publicly available through the Ontario court shed light on the discrete deal-making often involved in art restitution.

Over Vitebsk was sold to a European collector through Matthiesen’s gallery last year for $24m.

Matthiesen said in the 2022 affidavit that he was contacted in 2018 by Palmer, who offered his company’s services in locating and recovering art from Galerie Matthiesen, which Matthiesen’s father, a Jewish art dealer, had founded in Berlin. Matthiesen said he was initially uninterested in working with Mondex, but later struck a deal with the company along with other heirs of Galerie Matthiesen shareholders. Soon after, the heirs were informed they may have a claim to Over Vitebsk, which at the time was prominently featured in MoMA’s collection. The painting shows an elderly man with a rucksack over his back floating over the village in present-day Belarus where Chagall was born in 1887.

Matthiesen said he was surprised by the news of a possible claim over such a valuable piece of art. In an affidavit from 2022, he said he was doubtful during negotiations that any claims on individual works of art would be worth more than £1m, statements which Matthiesen said Palmer did not respond to.

Matthiesen alleged Palmer was already aware of the heirs’ connections to MoMA's Chagall painting during negotiations. If Matthiesen had been aware of the possibility of his claim on the Chagall, he would not have agreed to Mondex’s commission of 39% on the sale of recovered work, he said. Such a high rate is “well outside industry norms and standards for the recovery of a high-value artwork”, Matthiesen argued in a 2021 counterclaim filing, alleging that Mondex “concealed the existence and provenance of the Chagall painting to secure highly favourable terms and an exorbitant commission well in excess of industry standards, which they would not otherwise have been able to secure had they properly disclosed it”.

In a 2021 defence filed in response to the counterclaim, Palmer’s legal team refuted the accusation that Mondex had withheld information from Matthiesen and the gallery’s other heirs, holding that he had acted in their best interest. At the time they signed the agreement, he and the company did not know much beyond the fact that MoMA claimed its Chagall had once been owned by Matthiesen’s father’s gallery, he said. More research was needed to determine if it was the same painting and if it had been looted or stolen, according to Palmer.

“Artists, including Chagall, often created several versions of the same painting, commonly with the same or similar names. Only after Mondex was retained and engaged in considerable research and investigation was it able to come to any definitive conclusions,” the 2021 filing states. “Even at that point, ultimate success in the matter depended not only on confirming the identity of the painting but on being able to prove that the gallery did not receive fair market value for it. Only the absence of payment of fair market value would support a finding that the Chagall had been despoiled.” (Mondex claims research for the Over Vitebsk case consisted of eight historians working a collective 3,858 hours at a cost of more than $130,000.)

One year after Matthiesen’s father fled Germany in 1933, the gallery handed the painting over to Dresdner Bank in order to pay down debt, according to MoMA’s records of the painting. Dresdner Bank, once Germany’s second-largest bank, helped finance the construction of Auschwitz. (Dresdner Bank was still in operation until 2009, when it was acquired by Commerzbank.)

Former MoMA provenance researcher Lynn Rother claimed in a 2017 book that Galerie Matthiesen’s negotiations had been steered by a Jewish member of the bank’s board and that there is no evidence Over Vitebsk was passed to the bank under duress. But Palmer told The New York Times the amount of money the gallery owed the bank was far less than the value of the art that was handed over to cover the debt. Dresdner Bank sold Over Vitebsk in 1935, part of a deal with the Prussian finance ministry to stock the museums of Berlin with thousands of works of art. However, the Chagall painting instead ended up in New York, where MoMA acquired it around 1949.

The documents filed in the lawsuit and countersuit between Mondex and Matthiesen show that the two parties disagreed on how to handle many aspects of the restitution case, and how involved Matthiesen would be throughout the process. Matthiesen wanted to closely collaborate during the negotiations with MoMA and market the painting before its sale, and he objected to the involvement of the art dealer Daniella Luxembourg, whom Mondex often works with to broker deals for restituted works, according to the legal documents. Mondex claimed Matthiesen protested Luxembourg’s involvement in the case because she is a competing dealer whose gallery, Luxembourg + Co, has a space in London, but Matthiesen said it was because Luxembourg had been involved in English High Court legal proceedings related to client commission issues. Representatives for Luxembourg + Co did not respond to a request for comment.

The lawsuit was settled out of court, and both Matthiesen and Mondex declined to share details of the settlement or comment on it for this story.

MoMA did not respond to inquiries about the case or the $4m payment the museum previously said would be used to finance the Franz Matthiesen Fund for provenance research.