[ad_1]

In 1936, the Museum of Modern Art in New York mapped the history of abstraction—literally. The catalogue for “Cubism and Abstraction,” a major show that year, featured on its cover a diagram rendering how Post-Impressionism gave rise to Cubism, which then led to Suprematism, Constructivism, and so on and so forth. The exhibition’s purview was problematic for a number of reasons: Save for the unbilled African creators of sculptures included as reference points for certain kinds of Western abstraction, all of the artists were white. And then all but three of them were men. There was Robert Delaunay, but not Sonia Delaunay; Hans Arp, but not Sophie Taeuber-Arp; Alfred Stieglitz, but not Georgia O’Keeffe; Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, but not Lucia Moholy-Nagy; Pablo Picasso, but not Dora Maar.

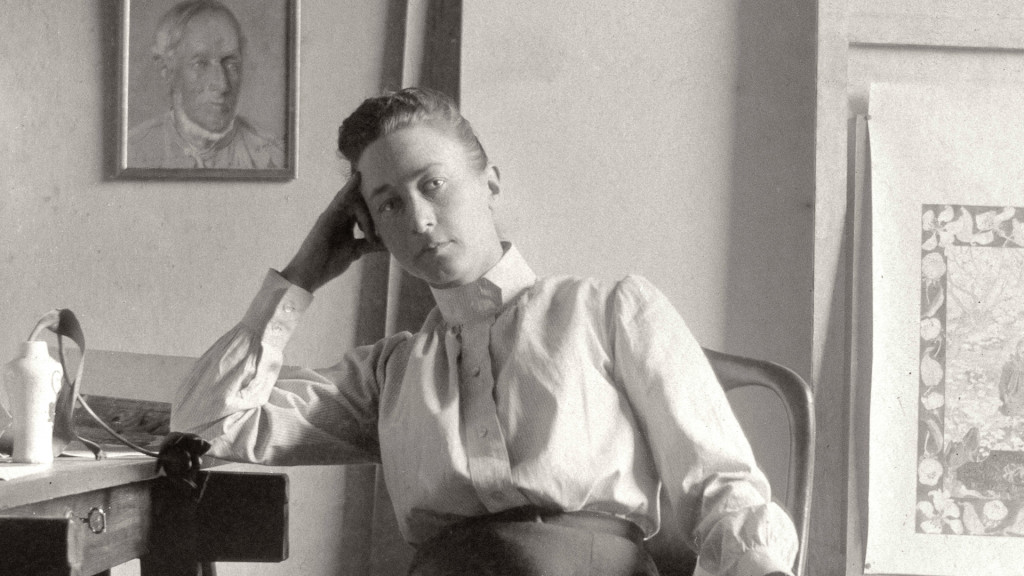

The show’s myopic view continued to inform the history of abstraction—even after MoMA attempted to revise it with a 2012 exhibition revisiting that prior survey. And one of the many figures who should have been included—especially with the luxury of retrospect—is Hilma af Klint, whose abstraction painting practice was intended to commune with altered states of being. Curious about the artist’s absence, filmmaker Halina Dyrschka reached out to MoMA to ask why, and went on to make Beyond the Visible – Hilma af Klint, a new documentary (to be released on streaming services on Friday) that considers af Klint as one of art history’s best-kept secrets. In the film, art historian Julia Voss calls that the MoMA omission “a hostility,” and Dyrschka clearly agrees as she treats af Klint as a true genius whose alluring mystical visions remained hidden away for decades until, in recent years, she became the subject of blockbuster retrospectives.

Stiftelsen Hilma af Klints verk

“In science, a citation can always be overturned,” artist Josiah McElheny says in Beyond the Visible. “But in art history, it seems like citations cannot be overturned.”

Coming into the world one year after the Guggenheim Museum’s “Hilma af Klint: Paintings for the Future” show drew a record-setting 600,000 visitors in New York, Beyond the Visible acts as a useful guide to the artist’s work, with a special emphasis on her biography. It traces the start of her career at Stockholm’s Royal Swedish Academy of Fine Arts, where af Klint began pushing against art-historical norms early on (an archivist points out that she drew nude male models—a no-no at the time), and continues following her artistic growth until she arrives upon a devotion to complete abstraction. There are stops along the way to consider her spirituality—an avowed Theosophist, af Klint formed the Five, a group that regularly held séances to commune with other worlds—and to revel in the majesty of some of af Klint’s more bizarre artworks, which feature twisting circles, swans that touch noses, wild wavy lines, and surreal swatches of color.

Dyrschka is not immune to the bland trappings that pervade documentaries about artists—she is too keen to rely on talking heads, and she might be a bit too determined to point out the similarities between, say, an out-of-focus moon and a circular blob on a canvas. But her film is supported by an enormous amount of research, and it piquantly points out connections between af Klint’s art and certain scientific trends of her day. Could those shaking lines that jut out of a cube in one painting be a reference to the new kinds of light waves being studied? Do the swans in her art refer to emergent biological investigations?

Courtesy Kino Lorber

As part of her research, Dyrschka provides some zesty historical details. She claims that Moderna Museet—Sweden’s most important modern art museum, where an af Klint show was to have opened in April before the coronavirus shuttered it—received an offer of works by af Klint during the 1970s—and that museum officials turned it down. (As af Klint’s nephew says, speaking of his aunt’s art, “No one understood what this is.”) And Dyrschka claims that the frequently repeated tidbit that af Klint never showed her abstractions during her lifetime may be a myth—according to a letter written by af Klint in 1928 that the filmmaker suggests is proof that the artist may have even exhibited some of her most famous works in London that year.

Some of Dyrschka’s claims are questionable—she proposes, for example, that Wassily Kandinsky might have met af Klint during the early 1910s, even though Guggenheim curator David Horowitz has stated otherwise—and she is quick to gloss over important historical details. (That the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and P.S.1 Contemporary Art Center in New York both staged af Klint surveys in the ’80s, years before the Moderna Museet’s 2013 show became a sensation, goes unmentioned.)

But ultimately, Beyond the Visible makes a good case for af Klint as a source of appreciation and study for the rest of time, as the artist’s works its way more and more into the mainstream. When MoMA reopened last fall, her work was included alongside that of Georgia O’Keeffe. Is a citation finally being overturned?

[ad_2]

Source link