[ad_1]

Robert Frank, Trolley – New Orleans, 1955.

©ROBERT FRANK/COURTESY PACE/MACGILL

It’s difficult to imagine a history of photography without Robert Frank, who died earlier this week at age 94. His photobook The Americans is widely considered one of the most important photographic documents of the mood in postwar America, and many have paid tribute to it—including critic Martin Gayford, who in his new book The Pursuit of Art: Travels, Encounters and Revelations, due to be released by Thames & Hudson on October 8, recalls chatting about the tome with Frank in 2005 in Zurich, the city in which the artist was born. Many have assumed that one would need a certain amount of confidence to produce images as indelible as the ones in The Americans, but not so, Frank told Gayford. “I always had my doubts about photography, because it’s made by a machine, then duplicated by a machine,” the artist said. An excerpt from Gayford’s book follows below. —The Editors of ARTnews

Robert Frank suggested I should meet him at a hot-sausage stand opposite the biggest tram station in Zurich, the one at the end of the line. It seemed quite appropriate, since Albert Einstein apparently first had an inkling of his theory of relativity while traveling on a Swiss tram. And Frank, you might say, was the man who brought relativity to photography. As his friend the poet Allen Ginsberg observed, he invented a new way of seeing, “spontaneous glance—accident truth.”

All the same, there was something alarmingly casual about this arrangement. I had never been to Zurich before, and therefore had no knowledge of its public transport routes or the snack stands that might be located nearby. So it was without much confidence that in the autumn of 2005 I caught an early plane, took the train into the city, and climbed aboard a tram.

However, near the terminus, there was indeed a little hot-dog stall. I stood next to it, uncertainly. Then, at the appointed time, an elderly man strolled along: Robert Frank arriving with an appropriate mixture of informality and precision. He was just what you would expect from a description by Jack Kerouac I had read an hour or two earlier, 30,000 feet up in the sky: “Swiss, unobtrusive, nice.”

Apologetically, he explained that he had chosen the bratwurst stand at the tram stop because it was easy to find and he liked the sausages (which were delicious). But it also seemed a Frank sort of spot: unexpected, informal, and with an excellent view of the world passing by.

Zurich looked as if it hadn’t changed much since Einstein had his tram-board epiphany, before the First World War. For that matter, Frank seemed so at ease in the city that he might have lived his whole life here. The latter would have been a false deduction. Frank had been around the globe before making this return visit.

As for the world itself, he observed as the trams rattled by, “it changes all the time and it doesn’t come back.” The photographer, therefore, is subject to a version of Heraclitus’s Paradox. That Greek philosopher noted that it is impossible to step into the same river twice—since by the time you do the water will have changed and so will you. Similarly, you cannot take the same picture twice, especially if, like Frank or his predecessor, Cartier-Bresson, you are operating amid the flux of reality.

Robert Frank, View from hotel window – Butte, Montana, 1956.

©ROBERT FRANK/COURTESY PACE/MACGILL

After a while, Frank suggested that we should move on from the tram stop to a nearby restaurant, the Haus zum Rüden, which was solid, old-fashioned, and quiet with good rösti on the menu. It represented, in a way, everything the young Robert Frank had escaped.

“When I come back here,” he exclaimed, “I can’t believe it. It’s privileged, that’s what it is! To me it’s a bit like a university campus. The water in the lake is clear when you look down—fantastic. When I was younger I walked away from it. Now I’m attracted to this peace.”

Frank was born in Zurich in November 1924, and comes from a cultured Jewish family. His father—who owned a business that imported radios—had moved to Switzerland from Germany. During the war Switzerland was an island of safety in Nazi-controlled Europe. But as soon as the war was over, Frank wanted to get away into the wider world. He didn’t want the smallness of Switzerland, nor did he want to follow his father into the business. One route out was suggested by a neighbor in the attic above the Franks’ flat.

“That man was a very big influence on me. He was a wonderful man—very quiet, he couldn’t hear very well, with a lot of knowledge of contemporary art. My father always talked about old art. So, because of this man, I saw that there was a different life than the one my parents led. He would gently tell me what you could do with photography.”

As a young man, Frank learned from older photographers, particularly Bill Brandt in London and Gotthard Schuh, who was Swiss. But—he added—“Some of the painters I knew taught me more about seeing than Brandt did.”

“I liked watching people,” Frank mused on his work of fifty years before. “I’d be very patient doing that, watching someone going down the street perhaps, tying his shoes. Then I’d have to be quick to take something. You have to be ready.” After a pause, he went on: “I was very free with the camera. I didn’t think of what would be the correct thing to do; I did what I felt good doing. I was like an action painter.”

Action painting, now more often called Abstract Expressionism, was an idiom that had only recently appeared when Frank first arrived in New York in 1947. Jackson Pollock began his drip paintings in that year. Mark Rothko and Willem de Kooning were at the height of their early maturity as artists; jazz too was all around, and Charlie Parker’s bebop a radical new musical style. All of this and the city itself struck Frank—aged 23 and just off a boat from Europe—as “wonderful.”

The voyage across the Atlantic had been exactly what the well-worn phrase describes: a rite of passage. “It was a long voyage on one of those Liberty boats that used to bring over arms to Europe during the Second World War, with only twelve passengers,” he told me, looking at the autumn sun on Lake Zurich: “There were storms, it was unforgettable for me.”

On board, he took a marvelous shot on the ship with a young man—another passenger—leaning on the rail and behind, slightly out of focus, the sea, a swirling chaos filled with infinite possibilities.

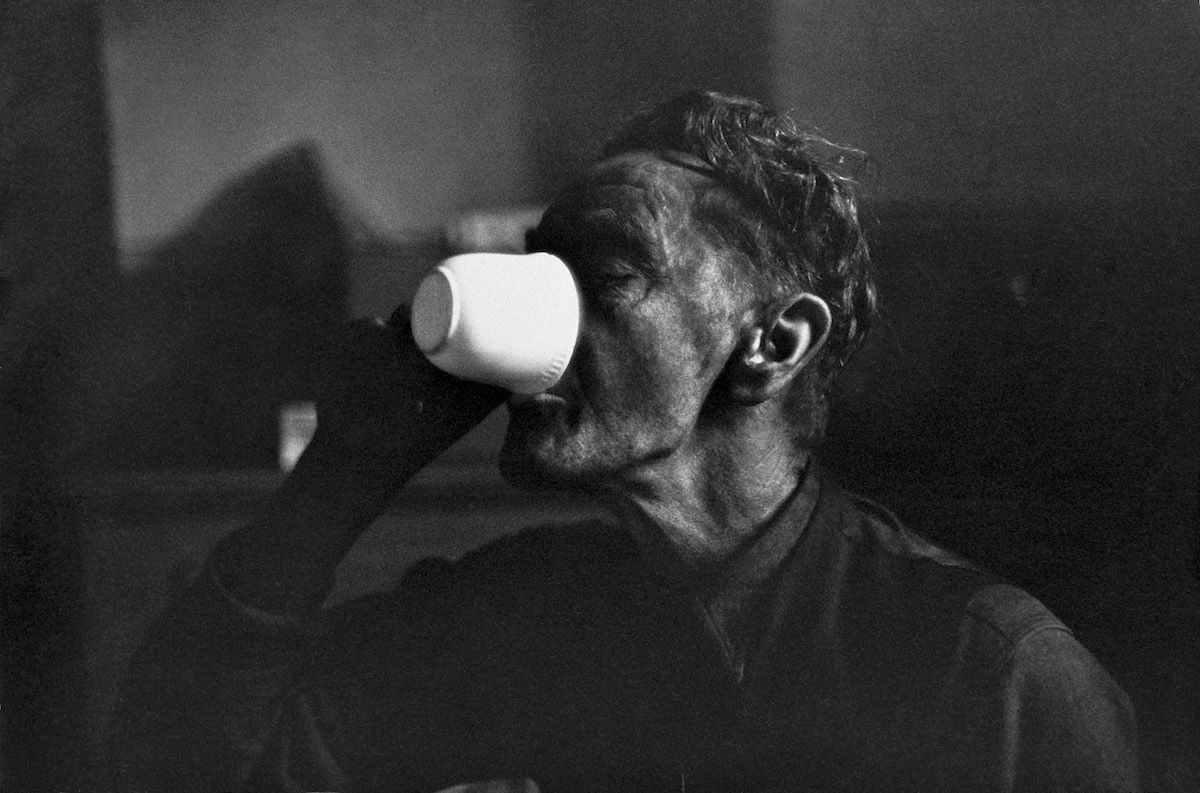

Robert Frank, Wales, Ben James, 1953.

©ROBERT FRANK/COURTESY PACE/MACGILL

In New York, Frank lived around 10th Street, then a warren of abstract artists’ studios. De Kooning’s studio was across the courtyard: Frank would watch him pacing backward and forward, agonizing about what brushstroke to make next on his current canvas. Later, around 1961, Frank took a superb shot of De Kooning standing in the street at night, the lights of the city shimmering in the background.

De Kooning was not, or not often, an entirely abstract painter. His pictures were more usually anchored somehow to the world, to a landscape or a human body. But content, De Kooning told the critic David Sylvester in a frequently quoted interview, was, as far as he was concerned, a glimpse. “A glimpse of something, an encounter, you know, like a flash—it’s very tiny, very tiny, content.” Nonetheless, that instant of revelation stayed in his mind while his picture might change all the time: “I still have it now from some fleeting thing—like when one passes something, you know, and it makes an impression.”

It struck me that Frank’s own photography could be described in the same way: fleeting glimpses. He agreed, then told an anecdote from half a century before. “One day De Kooning said to me that he had passed by the Matisse Gallery and seen the show from the street: ‘I didn’t need to go in, that was just enough.’ The way he said it was wonderful.”

Sometimes a glimpse can indeed be sufficient. Seeing—and understanding—can be extremely fast as well as very slow. You can look at a great painting, a De Kooning for example, for hours, for your whole life. But it’s also possible to comprehend a sight in an instant, far quicker than you could put it into words. The art historian and museum director Kenneth Clark said he could tell a good painting from a bad one while going past it at 30 miles an hour on a bus. He wasn’t much exaggerating. Sometimes you can.

The other thing Frank learned from painters, he went on, was to do with nerve. “These artists primarily showed me that if you had the courage to do what you felt was right, or what you really wanted to do, you could succeed. I would watch them very carefully. I was always a photographer, but I learned that if you followed this dream, you could do it, maybe not get to the top. But it was worthwhile doing it.”

Once in New York, he had got a job on Harper’s Bazaar, an achievement for an unknown youngster who had just stepped ashore. But after a while Frank didn’t want to work on fashion shoots, and he didn’t like the control that magazine editors had over his work. “When you are new to a country, you are excited, you watch, and I found out very quickly what I did not want to do.” Instead, Frank took off alone, taking his own kind of pictures.

In 1948, instead of doing fashion shots for Harper’s, Frank went to Peru. At that time he was reading the works of the French writer and thinker Albert Camus, whose central character in his novel L’Étranger of 1942 was a lonely misfit in an indifferent universe.

“I was an outsider,” Frank reflected, “I read a lot of French books then—all of Camus’s—which made a big impression on me. Maybe I didn’t understand them too well, but intuitively I got something of his view of the world, which influenced me. I felt I didn’t have to say, ‘Here’s a view of an ancient Inca city that I’ve brought back for you.’ I could just look at the country for myself.”

In the 1940s and 1950s he was an isolated individual with a camera, making choices, one after another, from the kaleidoscopic stream of appearances: an existential hero with a camera. After Peru, he went on to Paris, Spain, and Britain. In those days he felt “a bit like a detective” following someone—a city banker, for example, in dark coat and top hat patrolling the funereal streets of London—whose face or way of walking caught his attention.

Instead of single images, by the mid-1950s Frank began to think in terms of sequences, which added up to “a vision or something.” In 1956, he was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship that paid for a journey that took him through forty-eight states and from which he selected eighty-three shots that made up The Americans (1959), one of the most celebrated photo-books ever produced. Frank and his wife, Mary, just drove off, with two young children. She set out feeling they were going on “some sort of picnic.”

But their American odyssey turned out to be no picnic. In Little Rock, Arkansas, Frank was jailed for looking foreign and taking pictures. It took three days for him to get out. “I had never seen America from coast to coast,” Frank recalled. “It was my first trip really. It’s a very tough country, and I gravitate to people who are not winners. There were a lot of heartbreaking streets. I was drawn to that—how tough it was and how tough they were.”

The pictures Frank took en route were visibly done at speed, with minimal equipment—just a lightweight Leica hanging from a strap around his neck. Sometimes tilting, sometimes blurred, they looked fast.

While he was driving through the U.S., a then unknown writer called Jack Kerouac was trying to find a publisher for a book about just such a helter-skelter flight across the country. He called it On the Road. Frank met Kerouac in late 1957 or early 1958, after the book had finally come out. He was still searching for someone to publish the photographs from his own trip—which seemed shockingly raw and harsh to the middle-class New York publishers he was showing them to. This was not an America they recognized.

In contrast, Kerouac appreciated them on sight: “You got eyes,” he told Frank in compressed, hipster-speak. Kerouac wrote an introduction for The Americans, and the two men went off on a road trip together across Florida. Nonetheless, they saw this terrain differently. Although Kerouac had no time for the squares who inhabited much of the country, his writing is a paean to America in all its vastness and freedom. “Jack really loved the country,” Frank reflected. “His descriptions of America are among the most beautiful pieces of writing, to me.”

To his own European eyes, the U.S.A. was a fascinating place, but a dark one. “I didn’t feel like Jack about America. I feel more that way now. But America hasn’t changed; in fact I think it’s harder. Then there was really hope among the younger people, it was a great time to create something and to be in the company of people who would understand it. They called you a dirty beatnik, but it was fun. That doesn’t exist anymore. I was lucky to live through it and learn from it.”

Robert Frank, Parade – Hoboken, New Jersey, 1955.

©ROBERT FRANK/COURTESY PACE/MACGILL

Surprisingly, or perhaps not, as our conversation continued over another course and coffee in the elegant dining room of the Haus zum Rüden, it emerged that Frank was a little doubtful about the medium that had made him famous.

“I always had my doubts about photography, because it’s made by a machine, then duplicated by a machine. I always wished that I could start with an empty sheet and make something like a painter.”

He was surrounded by painters in New York—not only De Kooning but also Rothko, Barnett Newman, Helen Frankenthaler—and engagingly modest in his attitude to them. “Of course, they were artists, I was a photographer; so I was really on a lower level.” However, he had a painter’s instinct—the ability to see a potential picture almost at the speed of light.

Even in the confines of photography, Frank was restless. “I always had to move to another camera to get something different.” Soon he moved out of it altogether. “I didn’t want to have that Leica around my neck anymore; I said to myself, I’m through with that!” One day he went to see Kerouac and suggested they make a film. The result, Pull My Daisy (1959), had an improvised narration by Kerouac and featured various Beat figures including Allen Ginsberg, Larry Rivers, and Alice Neel.

In addition to film, Frank explored and invented various idioms: photo-collage, often with written messages on them; and multiple images set side by side, which were not far from the idiom of Gilbert & George’s pictures of the 1970s, or Rauschenberg’s Combines. In any case, as Frank pointed out, photography had changed hugely since the 1950s. Digitalization had made the image much more easily manipulable, closer in a way to painting. The hand, as David Hockney liked to point out, was back inside the camera.

During Frank’s lifetime, so much had changed, while other things—like this Zurich restaurant—had remained much the same. Now, here he was back again, sixty years after he had left. Before we said goodbye, he looked back, a little melancholy, but not regretful.

“I’m an old man now, and I can say it was very good, because it made sense somehow, much more than my father’s journey through life. That wasn’t a very happy trip. It all seems to fall apart at the end; like life falls apart, your body falls apart. But it’s good if you can work as long as you can.” Photographers, like painters, seldom retire.

Excerpted from The Pursuit of Art: Travels, Encounters and Revelations by Martin Gayford. ©2019 Thames & Hudson Ltd, London. Text ©2019 Martin Gayford Reproduced by permission of Thames & Hudson, Inc., www.thamesandhudsonusa.com.

[ad_2]

Source link