[ad_1]

Hannah Wilke appears lying on the floor, naked save for a neck brace, in a 1982 black-and-white photograph. The statement STAND UP HANNAH WILKE STAND UP is printed beneath the image on its mounting board. But the artist in fact seems unable to rise. Using headphones plugged into the board, visitors can listen to a song written and recorded by Wilke that instructs, “Stand up because you don’t belong. Stand up, if they’re too right, they’re wrong,” equating the physical act of standing with asserting one’s beliefs while highlighting the difficulty and exhaustion that can accompany either effort.

In Wilke’s posthumous career-spanning survey at Ronald Feldman, Stand Up Hannah Wilke was displayed near the threshold between the gallery’s two main exhibition spaces. The first room focused on the artist’s work of the 1960s and ’70s, including the self-portraits she created in an attempt to counter feminine stereotypes. Wilke appears, typically topless or completely nude, in poses that evoke fashion photography and pinups. But sometimes, her faux glamour shots come with a twist: she can be seen wielding a gun or accompanied by cautionary text, such as BEWARE OF FASCIST FEMINISM. The second room showcased her body too, this time in work she made following her 1987 diagnosis of lymphoma, the disease from which she died in 1993.

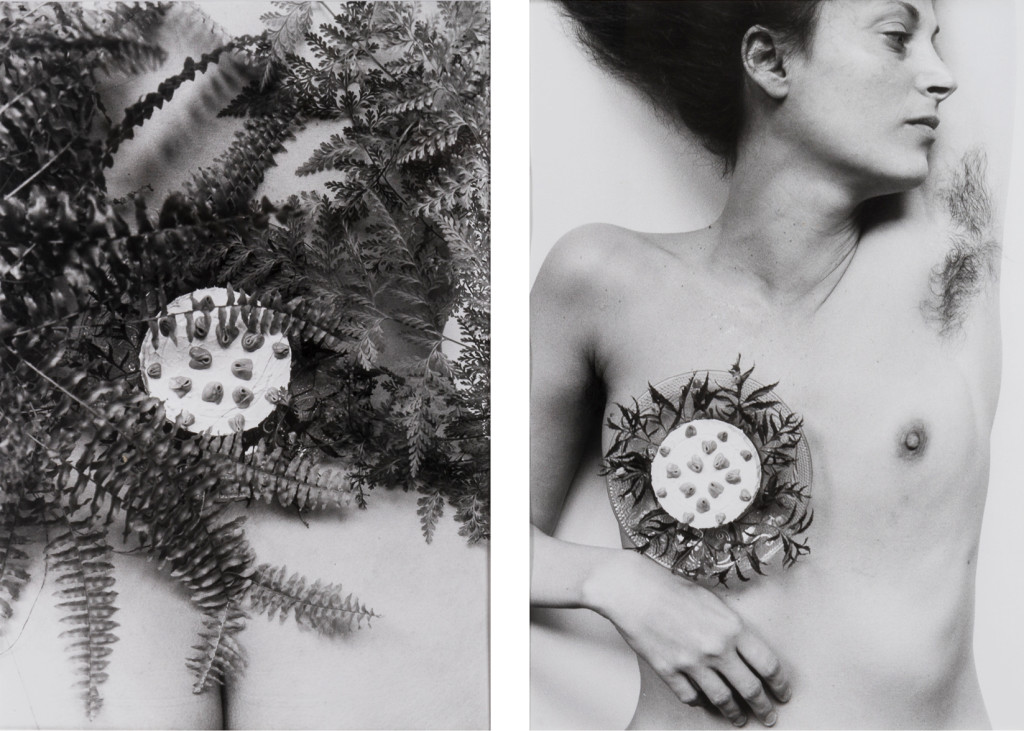

The show’s organization emphasizes how Wilke’s concern with sickness and vulnerability predated her own diagnosis. Stand Up was shown near a 1978–81 diptych comprising one photograph of Wilke’s shirtless mother post-mastectomy and another of the artist with several small ritual objects placed on her bare breasts, perhaps an attempt to ward off her genetic predisposition to cancer. Nearby, Breastplate (1981) showed Wilke with a small dining plate framed by a wreath placed over one breast as if shielding herself or performing a gesture of solidarity with her mother. While cancer is often described as a “battle” that can be won through aggressive treatment and will power, Wilke’s preventive efforts don’t read as heroic.

The plate in Breastplate is covered in tiny sculptures of vulvas—a common motif for Wilke. Made from clay, gum, or kneaded erasers, such sculptures (varying somewhat in size) were arranged throughout the show in grids on plinths, dotting pieces of paper, or stuck to photographs of sites like the New York Public Library. They’re also shown adorning the artist’s body in her self-portraits. The sculptures, created with a single twist or two in the material, appear as if they could be easily undone. While many of Wilke’s contemporaries—Carolee Schneemann, Judy Chicago—celebrated the potential for power in the female body, Wilke was intent on placing beauty and agency on equal footing with vulnerability, especially following her mother’s illness.

Venus, the Roman goddess of love and beauty, regularly figured in Wilke’s work as a model of femininity. The show included the series “Venus Pareve” (1982–84)—miniature nude self-portrait busts originally cast in edible kosher chocolate, then re-created in plaster. The photograph Venus Envy (1980) is a crotch shot wherein Wilke’s pubic hair covers a man’s balding head. The last series the artist created is titled “Intra-Venus”; it includes photographs of Wilke and painted self-portraits she made while undergoing chemotherapy. Her increasing hair loss marks the passing of time in three larger-than-life photographs shot in February, May, and June of 1992. In them, she’s visibly sick, though not inviting pity: in one, she’s stoic (leveling an even stare through her wet, thinning hair); in another, silly (sticking out her tongue).

While critics have never dared question the seriousness of Wilke’s work concerning cancer, her earlier work was regularly dismissed as that of a narcissistic pretty woman who was neither critical nor feminist. Writing in 1976, Lucy Lippard called her work “politically ambiguous”; just over a decade later, Judith Barry and Sandy Flitterman argued that it “ends up by reinforcing what it intends to subvert.” Looking at Wilke’s two bodies of work together, it’s clear that the only major difference between them is how she looked. In both, she presented herself, often nude, displaying a range of emotions. But with both, many people overlooked the complexity of her subject, seeing only a naked woman in the first and a cancer patient in the second. Wilke insisted on being unashamedly herself against all taboos, bearing her vulnerabilities alongside her desirability.

[ad_2]

Source link