[ad_1]

Late one night in the fall of 2012, 17-year-old Brittany Aragon overdosed. She took four Valium pills, lay down in bed and waited.

She was nervous, she said, but the thought of having to go back to the gym and face her coach, John Geddert, terrified her more than taking the pills.

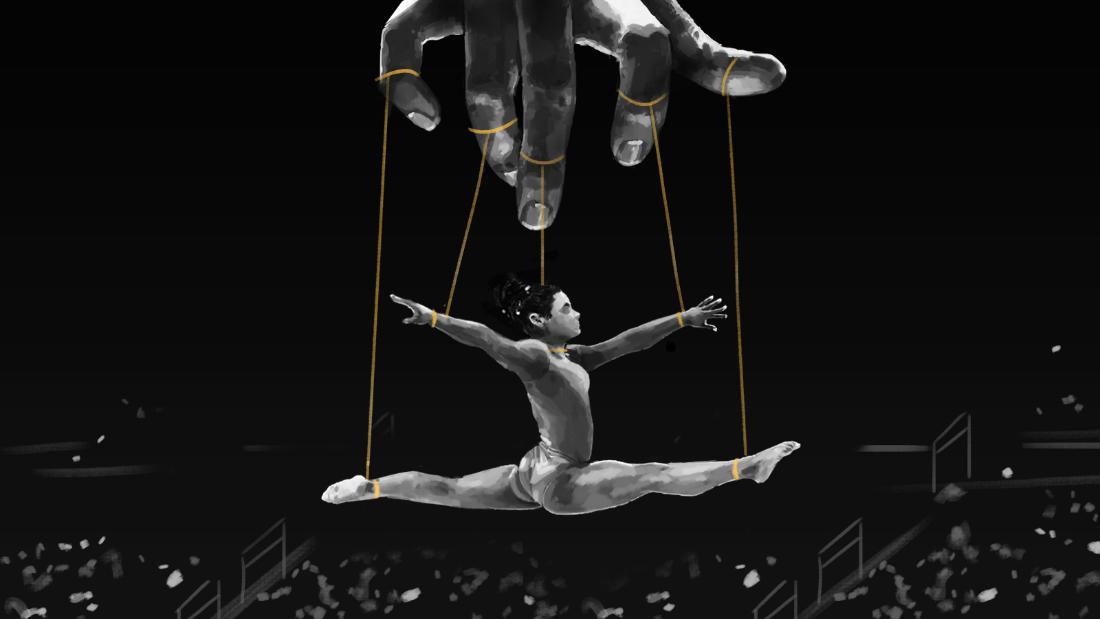

While Larry Nassar was sexually abusing gymnasts in the back room of Twistars Gymnastics in Lansing, Michigan, Geddert – the famed Olympic coach and then-owner of the gym – was subjecting them to a different kind of horror: routinely ignoring their injuries and verbally assaulting them, according to former gymnasts and their families.

John needs to go down as hard as Larry did. Sometimes I think he was worse.

Ken Lorencen | Father of Bailey Lorencen, a former Twistars gymnast

Seven gymnasts and their families gave CNN detailed accounts, medical records and electronic communications that they say document years of abuse at the hands of Geddert.

One says he injured her so badly it ended her career at age 17. Another says he failed to get her medical attention after she broke her neck at practice, an injury she said the doctor told her could have left her paralyzed. A third gymnast said Geddert made her train on a broken leg for nearly a month when she was 13. Two teenage gymnasts attempted suicide. All the young women who spoke to CNN said he repeatedly disregarded their injuries.

“John was always scary, even when he wasn’t my coach yet,” said gymnast Bailey Lorencen. “He would be throwing water bottles at the girls in the gym and get in their face and scream at them.”

Geddert coached through fear, his gymnasts say – and his abuse often led them to seek emotional comfort with Nassar, the doctor at Twistars.

“Larry would act like he cared about us,” said Brittany, who is speaking out for the first time since her overdose six years ago. Many gymnasts complained about Geddert to Nassar, she remembered, and Nassar would tell them, “This is just how John is, he wants the best for you.”

Nassar was sentenced to up to 175 years in prison this year, after more than 150 women and girls testified he sexually abused them over the past two decades.

“As parents, of course we’re happy that Larry is behind bars,” said Ken Lorencen, Bailey’s father. “But John needs to go down as hard as Larry did. Sometimes I think he was worse.”

Nassar and Geddert worked together for nearly 20 years. They were longtime friends; Geddert was in Nassar’s wedding party in 1996. The following year, a Twistars parent told Geddert about Nassar’s behavior, alleging sexual abuse, assault and molestation, according to a federal lawsuit. The suit, which is ongoing, says Geddert took no responsible action.

He coaches and lives in a narcissistic manner

A former Twistars coach | Referring to Geddert in a 2013 letter to USAG

The sport’s governing body, USA Gymnastics, first learned about Nassar’s abuse in the summer of 2015 and started an investigation. Even after USAG fired Nassar that summer – and Michigan State University fired him the following year – Geddert continued to support him. In September 2016, Geddert was quoted as saying Nassar is “an extremely professional physician” who “goes above and beyond” for his gymnasts.

During his time treating gymnasts at Twistars, Nassar protected Geddert as well. Parents of gymnasts said he tried to persuade them not to file charges for Geddert’s alleged abusive behavior. Documents obtained by CNN show that Nassar tried to intervene after one woman filed a police report against Geddert, saying he pushed her granddaughter against a wall and stepped on her foot.

In 2013, USAG received a letter from a former Twistars coach detailing complaints of verbal and physical abuse by Geddert, according to documents obtained by CNN. The letter said Geddert “coaches and lives in a narcissistic manner” and “should not be allowed to coach gymnastics.”

It’s hard to explain the pressure that John puts on you

Bailey Lorencen | Former Twistars gymnast

USAG commissioned an investigation and hired private investigator Don Brooks to look into the complaints against Geddert described in the letter.

Brooks said his investigation corroborated much of the allegations in the letter, yet Geddert was allowed to continue coaching. In a summer 2014 meeting with USAG’s president, Geddert agreed to make changes to his coaching style, according to documents exclusively obtained by CNN. “Specific directions and expectations were crafted for Geddert,” documents show.

USAG did not suspend Geddert until four years later, when his name came up during the victim impact statements at Nassar’s sentencing. One gymnast told the court Geddert deserved to “sit behind bars, right next to Larry;” another called Geddert an “enabler” and a third said he was “physically abusive.”

The sport is not for the faint of heart, gymnasts and their parents said, and they would often put up with abuse and hardship to reach their goals. The question, for many then, was a matter of degree.

“It’s a tough sport,” said Lisa Hutchins, a former Twistars mother and coach. “It takes tough parents and tough kids. The culture is toxic. To be the best, we believed kids need to be coached with a certain degree of threatening. John was really good at pitting parents against each other to keep it that way. He wanted control over what the parents and kids said or did. And if you stood up to him, your kid would pay.”

Geddert was known for getting his gymnasts college scholarships, another way they say he exerted power over them.

“It’s hard to explain the pressure that John puts on you,” said Bailey. “That college scholarship is everything.”

After his suspension from USAG on January 23, 2018, Geddert announced his retirement and signed ownership of his gym to his wife, Kathryn, a day later.

The Eaton County Sheriff’s office is investigating Geddert, Detective Chris Burton said. He could not provide details, saying people are still coming forward. Three gymnasts and their parents who have spoken to Burton say he’s interviewing “dozens” of people and may be looking at child abuse charges.

Geddert is a named defendant in the ongoing federal lawsuit that claims he failed to protect the gymnasts at Twistars from Nassar’s abuse. The suit, filed in early 2017, states that all defendants, including USAG, MSU, its board of trustees and Twistars, knew or should have known about Nassar’s abuse and referred gymnasts to him nevertheless.

Twistars and Geddert filed a motion to dismiss the lawsuit in January 2018, refuting allegations that Geddert was a witness to Nassar’s abuse and failed to act, and stating Geddert “was just one person in an extremely long line of people who were fooled by Nassar.” MSU has also filed a motion to dismiss.

“In Plaintiffs’ quest to bring Nassar to justice, they overzealously and wrongly accuse Mr. Geddert and his gym, Twistars, of a litany of wrongs, none of which are well founded in either the facts or the law,” Geddert’s motion states.

James White, an attorney whose firm is representing dozens of the gymnasts, said he hopes the lawsuit will result in “institutional change” at MSU and universities across the country.

“We are cautiously hopeful this can be resolved through mediation,” White said. “But we’re aggressively preparing for trial.”

Geddert and his attorney declined to comment for this story.

Training with Geddert meant being constantly insulted and humiliated, Brittany said.

Whenever he was unhappy with her, she said, there’d be consequences. Geddert would make her hang from a bar and bring her toes to her hands, climb a rope up to the ceiling and run lap after lap – because, at 5 foot 3 and 119 pounds, he found Brittany to be too heavy.

If she didn’t perform her exercises perfectly, she said, he’d scream one of his favorite threats: that he was going to “beat her like a red-headed stepchild.”

“It’s his eyes,” Brittany added, “they pierce through you. You know he’s not kidding.”

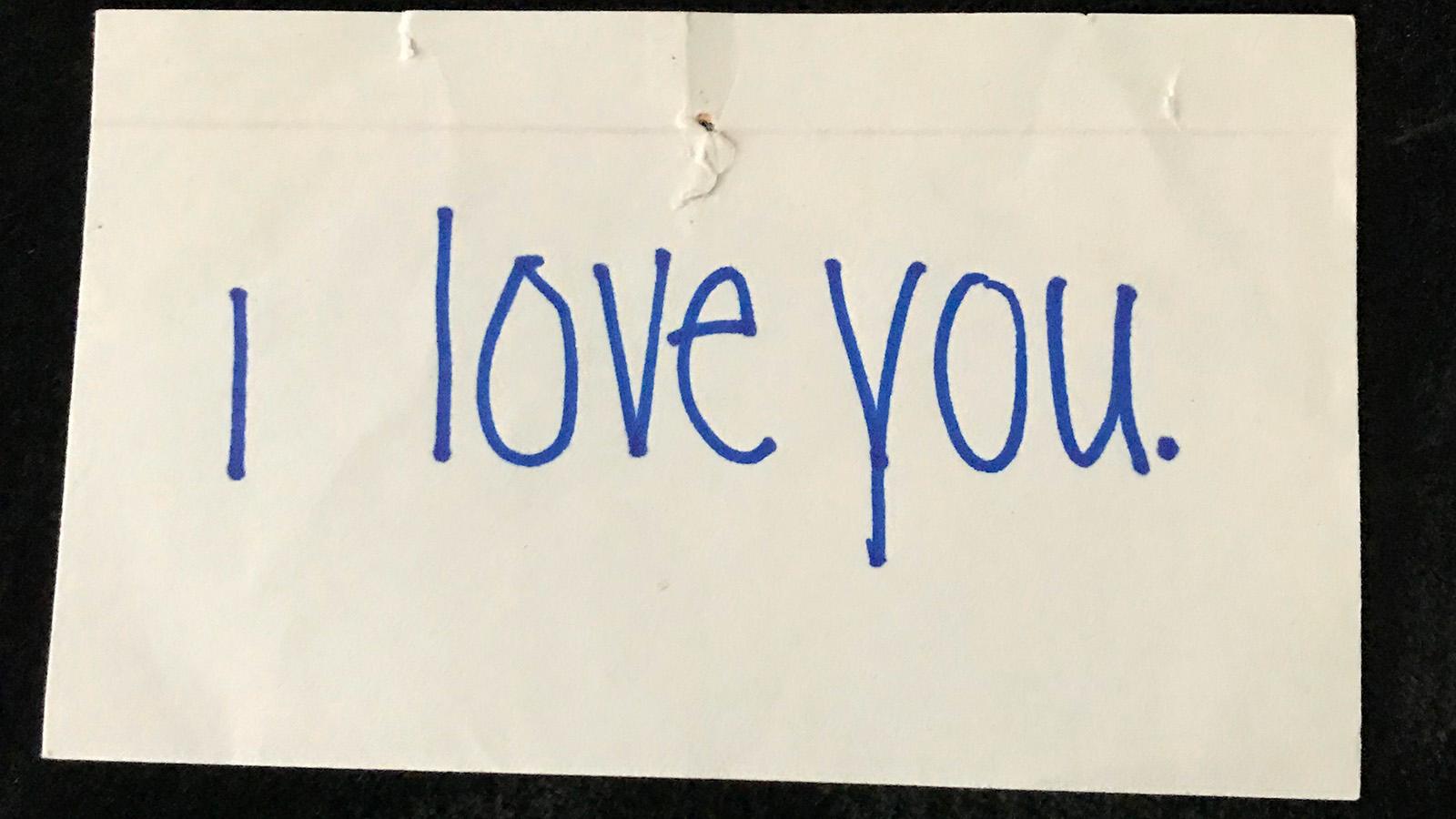

Several hours after she overdosed on the Valium – pills left over from a gymnastics injury – her father said he found her face-down on the floor. On an index card, she’d written “I love you” with blue highlighter. Her mother, Lisa, still keeps the note in her Bible.

Her father, Freddy, said he slapped her face, trying to wake her up, while her mother called an ambulance. The paramedics rubbed her chest with their knuckles to test for unconsciousness, Brittany remembered. She heard and felt it all, she said, but was unable to move or say anything.

At the psychiatric hospital where she was admitted, she says, she tried to tell doctors that Geddert was abusive, but she’s not sure they understood how bad it was.

“They told me I shouldn’t care what he thinks and asked what I could be doing differently,” she remembered. “But what could I do? I’m a 17-year-old girl up against this old man. What could I do?”

She spent three days at the hospital. Then, Brittany said, Nassar texted her.

Ironically, Larry was our safe haven

Lindsey Lemke | Former Twistars gymnast

He told her she needed to apologize to Geddert and his wife if she wanted to return to the gym. She thought it was weird, she said, but didn’t have to be convinced to apologize. “I didn’t know how to move forward from this, my parents didn’t know how to move forward, and I trusted Larry.”

Brittany said she drafted a text-message apology, and Nassar proof-read it.

It wouldn’t be the last time Nassar would intervene on Geddert’s behalf.

Makayla Thrush showed potential as a young gymnast and came to Twistars at age 7.

“I always wanted to go to Twistars,” she said, noting it’s where 2012 Olympic gold medalist Jordyn Wieber trained. “It’s the best gym in the country.”

Practices at Twistars were long, running from 3:30 p.m. to 8 p.m., five days a week, the gymnasts said, and Geddert wouldn’t accept any excuses to skip practice. They covered their bleeding hands in chalk for skills on the bars, and their bruised limbs landed on the beam time and time again, the five women remembered. Anyone who came late had to climb the rope to the ceiling using only their arms.

You told me to kill myself, not just once but many times

Makayla Thrush | Former Twistars gymnast

“If you embarrassed John at a meet, there’d be consequences,” remembered Lindsey Lemke, a Twistars gymnast from age 8 to 16. In her victim impact statement at Nassar’s sentencing, she said Geddert deserved to be behind bars with Nassar.

If one of the girls broke down, he’d yell “No tears on my floor!” several gymnasts recalled.

During a summer camp training session, Makayla says she was told to do an exercise on the vault – the classic run to a springboard that launches gymnasts over a vaulting table. She said she didn’t think she could do it, prompting Geddert to come over.

He told her she was a “disrespectful bitch” and that she should “climb up to the rafters, jump off and kill myself,” she remembered. Makayla was 10 years old at the time.

Makayla’s mother, Sallie Thrush, remembers her daughter running up and telling her what the coach had said. Geddert followed after Makayla, still yelling, her mother said.

But Makayla didn’t quit. “My big dream was college gymnastics,” she said, “and John had a reputation for getting you scholarships.”

For gymnasts with dreams of scholarships, competing at an elite level or even going professional, Geddert is almost unavoidable, gymnasts and their parents told CNN. His website boasts his accomplishments: 17-time state, regional or national coach of the year, 2011 USA World Championship team head coach, 2012 USA National Elite coach of the year and, most famously, the coach who led Jordyn Wieber and USA’s “Fierce Five” gymnastics team to Olympic gold in 2012 in London.

In 2012, when Makayla was 16, Nassar diagnosed her with a severe case of mononucleosis, her mother said. She missed 56 days of school, but Geddert would not let her miss a single day at the gym.

In early 2013, while she was still sick with mono, Makayla was told to do a release skill, swinging between bars of alternating heights. Her mother had come to watch that day and remembered seeing her swing from the high bar. Makayla was supposed to let go and catch the low bar, but instead Geddert grabbed her mid-air and threw her onto the low bar, Makayla recounted in her victim impact statement at Nassar’s sentencing. The injury left her with a black eye, swollen lymph nodes and stomach pain.

Fearing Geddert’s wrath, Makayla kept training for the next meet, her mother remembered.

By then, Makayla was still hurting, and it showed. “She didn’t do very well at the meet,” Sallie Thrush said. “She still won, but she wasn’t perfect. It made John so angry that he screamed at her until the judges gave him a warning.”

After the competition, Makayla doubled over in pain. In the week that followed, Nassar tried acupuncture on her to no avail and ultimately sent her to get an ultrasound at MSU’s radiology center, her mother said. Doctors found ruptured muscles in Makayla’s stomach, Makayla and her mother said.

The injury ended her gymnastics career, they said, leaving Makayla to struggle with anxiety and depression.

Two years after she quit gymnastics, she, too, attempted suicide.

“You told me to kill myself, not just once but many times,” she told Geddert in the victim impact statement she read at Nassar’s sentencing. “And unfortunately I let you get the better of me, because after you ended my career, I tried.”

“There were a lot of injuries that John didn’t believe were injuries,” former Twistars office manager Priscilla Kintigh told CNN.

Bailey Lorencen was 12 when she fell from an 8-foot-high bar during practice and landed on her head, she said. Geddert came over, decided it was a muscular injury, and told her to sit in splits, Bailey remembered, with her legs extended 180 degrees in opposite directions for the rest of the session – about an hour and a half. When her father, Ken, came to pick her up, he said, Geddert didn’t tell him about the fall. He only learned about it from his daughter’s friends later.

That night, unable to get up from the couch, Bailey was rushed to the hospital, she said. Scans showed fractures in her C2 neck vertebrae. Bailey and her father said the doctors told them it was a miracle she wasn’t paralyzed.

Two years later, Bailey started having back problems, her father told CNN.

At practice in the fall of 2010, she was in so much pain that she fell during a tumbling pass on the floor and landed on her face, Bailey recalled. Geddert got angry, yelled at her and made her do sprints. Later, at the hospital, she said she prayed the MRI would show a broken back, just so she could prove her injury to Geddert.

Her prayers were cruelly answered – but after more than a year in a back brace, her injury hadn’t healed. Last year’s X-rays still showed a fracture in her L5 spinal vertebrae, Bailey and her father told CNN.

When Izzy Hutchins was 13, continuous pain in her lower right leg made her worry she couldn’t compete, she said. When she mustered up the courage to tell Geddert about it, he got angry and sent her to Nassar. Nassar didn’t find anything, she said, and told her to keep practicing.

Weeks later, she was in too much pain to do her floor routine, she said, so Geddert made her replace the tumbling passes with forward rolls, “something that a 3-year-old would do,” she said. “He made the entire gym stop to look at me. To this day it feels super humiliating.”

She said she turned to Geddert’s wife, saying she couldn’t walk and needed help. But Kathryn sent her back to Geddert, who told her to “pack up her shit and get out of his gym.”

Izzy said he followed her to the locker room, put his face inches away from hers and screamed that she was a “spoiled f***ing brat.”

“I remembered wiping his spit off my face,” she said.

An MRI scan later that afternoon showed a broken fibula in her right leg, Izzy and her mother said. It had been broken for over a month.

Geddert provided Nassar with unrestricted access to the girls every Monday night at 8 p.m. in the back room of Twistars, the gymnasts said. That’s when Nassar would tend to their injuries and, in many cases, abuse them.

During the 20 years Nassar and Geddert worked together, Nassar would console the gymnasts after Geddert aggressively disciplined or punished them.

“Ironically, Larry was our safe haven,” Lindsey Lemke told CNN.

Geddert was known to walk in unannounced as they met with Nassar, the gymnasts said. In her impact statement, Makayla said Geddert would make similar surprise visits to the locker room as the girls were changing.

No allegations of sexual misconduct have been raised against Geddert. But multiple gymnasts said he made frequent sexual comments to the girls, suggesting they looked like Victoria’s Secret models in their pink and black leotards, commenting on their developing bodies and joking that they could always become strippers if gymnastics didn’t work out because they could climb a pole so well.

Brittany, Bailey, Izzy, Lindsey and Makayla all told CNN that Nassar would clean up after Geddert.

“Larry, out of everyone, knew exactly what was going on. We all confided in him,” said Bailey.

“He would sort of justify it and say that John just wanted us to do well,” Izzy said.

Police records show that on October 15, 2013, Geddert allegedly lashed out against an 11-year-old gymnast, stepped on her foot, twisted her arm and put her up against the wall. Her grandmother filed a police report and, the next evening, two officers visited Geddert at his house. According to the police report, Geddert said it was a “discipline meeting” and that he did not assault the child.

On the morning of October 17, Geddert’s wife emailed the grandmother asking to talk by phone. According to documents obtained by CNN, Kathryn followed up with a Facebook message hours later:

“This complaint could take away our lively hood! What we have worked 30+ years for, 40+ jobs, 1200 gymnasts future at the gym.”

At 10:24 p.m. that night, she sent a final Facebook message: “Can you please re-think this complaint?”

Kathryn Geddert declined to comment for this story.

The next day, Geddert himself sent a text message:

“The accusations pending could put me on the banned list for USAG. … I am not perfect but I certainly am not one to harm children. I certainly would not be at this point in my career if that were ever my intentions.”

Four days later, Nassar chimed in as well.

“Just ask to drop it, if you are not 100% sure you want to close John’s gym and have him banned from USA Gymnastics for the rest of his life,” he told her in a Facebook message, according to documents obtained by CNN. “Having the police come to his house was a huge lesson for him already.”

After Brittany’s suicide attempt, she and her father – not knowing how else to move forward – met with Geddert and his wife to discuss her return to the gym.

Nassar told Brittany that her mother shouldn’t attend the meeting, she said, because Geddert “didn’t do well with women.”

At the meeting, Brittany and her father remembered Geddert saying that if word got out Brittany had overdosed, he would lose his gym and his money and that Kathryn would leave him. He suggested Brittany would lose her scholarship at Western Michigan University if the coach there – a friend of Geddert – found out. “What college is going to want someone who deals with problems like this?” Brittany remembers him saying. By the end of the meeting, Brittany and her father said, they agreed to say she had been sick.

“After Brittany’s episode, Larry called me every single day to check whether we’d be filing charges against John,” Brittany’s mother, Lisa, said.

If I said anything, my fear was that Makayla would pay the consequences

Sallie Thrush | Mother of Makayla Thrush, former Twistars gymnast

Also at the meeting, on Nassar’s advice, was sports psychologist Geffrey Colón.

Brittany met with Colón a few more times, always at a Wendy’s restaurant. She said it was pointless. He suggested the root of the problem was her fear of doing “Jaegers,” an exercise that involves swinging around the high bar, letting go in mid-air, flipping around and catching the bar again.

“I would never catch the bar again during practice while John was yelling at me,” she said. “But the problem wasn’t the skill.” At meets, Brittany said, Geddert wouldn’t be yelling at her while she was performing. “And I would always make the catch.”

Colón said Brittany’s case was different from the 25-30 other teens Nassar and Geddert had referred to him over the years. Those sessions focused on developing mental strategies to create peak performance, Colón said.

“I was hesitant when I received the initial phone call from Larry (about Brittany),” he said. “These cases are not my strength, but Larry assured me that she had been cleared by the hospital and her psychologist.”

I didn’t know how bad it was until Brittany took those pills

Lisa Aragon | Mother of Brittany Aragon, former Twistars gymnast

Colón said he was trying to help her get back into the sport and the gym.

“I never got into (Brittany’s suicide attempt),” Colón said. “We focused on reintegration into the sport and coping skills. There was an aspect of the athlete taking things too personal.”

Colón said he met Nassar and Geddert in the early ‘90s at a different Michigan gym. Colón’s daughter trained at Twistars when she was younger, he said, and the three men would at times socialize together.

Colón said he believes “John Geddert really cares about his athletes.” Colón admits there are “aspects of a negative coaching style … but he is much better now than he was 20 years ago. The evolution has been very apparent to me.”

Though all of the gymnasts who spoke to CNN said they experienced escalating injuries and verbal thrashings under Geddert, few of their parents dared to stand up to him.

Fears of retaliation against their children and the prospect of losing possible college scholarships allowed Geddert’s tyranny to go unchallenged, the parents said. Even this year, long after the women had left the gym, parents and their daughters still expressed fear of speaking out.

“He has a look about him, a glare in his eyes, how he gets in your personal space and intimidates you,” said Makayla’s mother, Sallie Thrush. “And if I said anything, my fear was that Makayla would pay the consequences.”

I can say with certainty that John Geddert should not be allowed to coach gymnastics

A former Twistars coach | In a 2013 letter to USAG

The same fear also kept the children from telling their parents how badly Geddert behaved.

“I knew he was tough,” said Brittany’s mother, Lisa Aragon. “But I didn’t understand how bad it was until Brittany took those pills.”

“When your child shows potential, you start thinking, ‘Hey, maybe we’ll get college paid for,’” said Ken Lorencen, Bailey’s father. “And he does win them all. So when you see her so successful, and you see the smile on her face when she wins, you keep going.”

Lorencen was so dedicated to his daughter’s gymnastics career that he cleaned Geddert’s gym almost every night for nearly three years to pay for her lessons.

According to documents received through a records request, one mother who took her two girls out of Twistars confided in a friend: “I am afraid to do anything. We are still in the sport and whether people like him or not, he has people in his pocket and will blackball my kids. I can’t risk that. I’m seriously afraid to get involved. He has so many people that have covered things up for him.”

CNN found four police complaints against Geddert dating back to 1986, all for assault in or around a gym. No charges were ever issued.

The most recent complaints were filed with the Michigan State Police. The first was from a Twistars parent and coach in 2011 after she and Geddert got into a verbal argument and he chest-bumped her in the parking lot when she tried to get away from him. The second complaint, in October 2013, came from the woman alleging Geddert had assaulted her 11-year-old granddaughter.

Police records show that Geddert completed counseling after the 2013 incident. In a letter to the young gymnast exclusively obtained by CNN, Geddert wrote: “I was informed our conference in the locker room on October 16, 2013, frightened you. That was not my intent when we met for approximately 45 seconds. I was genuinely concerned about your safety during the exercises and held your arm to impress upon you the need to perform the exercises properly to minimize the risk of serious injury.”

The incident led the grandmother to pull her granddaughter out of the Twistars gym. Geddert gave her a refund on the Twistars leotards she’d just bought and now would never use.

On December 4, 2013, a former Twistars coach wrote an eight-page letter to the then-president of USA Gymnastics, Steve Penny.

“I can say with certainty that John Geddert should not be allowed to coach gymnastics,” the former coach wrote. “I am truly concerned for the well-being of the athletes under his care. He coaches and lives in a narcissistic manner, attempting to control others by means of fear and intimidation. I have witnessed the use and abuse of multiple gymnasts under Geddert’s care and have concerns for their bodies, health, interests and overall psychosocial development.”

The letter was provided to Don Brooks, the independent investigator hired by USAG in February 2014 to investigate the complaints detailed in the former coach’s letter.

“The letter became my starting point, I treated it as a map to get the investigation started,” said Brooks.

Between February and May of 2014, Brooks interviewed gymnasts and their families. He would not discuss the details of those interviews but confirmed that much of the letter was corroborated.

All (the families) expressed disappointment that John Geddert did not receive a suspension or harsher punishment

Don Brooks | Private investigator hired by USAG

By the end of May 2014, he sent his findings to USAG. Among them, Brooks said, were Brittany’s suicide attempt and the incident at Twistars that left Makayla with a black eye, swollen lymph nodes and stomach pain.

In August 2014, Brooks was instructed by USAG attorney Scott Himsel to get in touch with the families a final time. According to documents obtained by CNN, Brooks let them know that Geddert met with Steve Penny and a USAG board member. “As a result of their meeting,” Brooks wrote, “Geddert has agreed to make changes in his coaching style. Specific directions and expectations were crafted for Geddert.”

In his report to USAG, Brooks said he wrote that “all (the families) expressed disappointment that John Geddert did not receive a suspension or harsher punishment.”

Penny, who stepped down as USAG’s president in March 2017 amid Nassar’s sexual assault scandal, told CNN he could not comment on the letter, the investigation by USAG or anything else related to Nassar or Geddert.

Geddert kept coaching until his January 2018 suspension from USAG.

USAG confirmed Geddert’s suspension earlier this year citing article 10.5 of its bylaws, allowing interim measures to be imposed to ensure gymnast safety in the presence of sufficiently serious allegations. But the organization said it could not comment further “as this is a pending matter.” USAG reiterated its commitment to athlete safety and creating an empowering culture for its gymnasts.

Brittany Aragon left Twistars in the summer of 2013, 11 months after she overdosed. That August, she started college at Western Michigan University. But even there, 70 miles away from Geddert’s gym, she said she couldn’t escape him.

When she arrived at WMU, Geddert’s friend was no longer coaching there, so he called the new coach, Penny Jernigan. Jernigan said he wanted to talk about the five Twistars athletes at the school. Brittany was one of them. “When he talked about Brittany, his tone changed,” she said. “He complained about her and said she doesn’t like hard work.”

It took a long time for her to understand I needed to know about her injuries in order to keep her safe, not punish her

Penny Jernigan | Brittany’s gymnastics coach at WMU

“Brittany was a quiet girl,” Jernigan recalled, “and the only one of the Twistars girls to complete all four years.”

But it wasn’t easy for Brittany to trust her new coach, Jernigan said.

“She had never known a coach who would look after her,” she said. “Talking about her injuries was challenging. She was used to getting in trouble when she said she was hurting. It took a long time for her to understand that I needed to know about her injuries in order to keep her safe, not punish her.”

During her time at WMU, just hearing the words “clear the floor” – which had been Geddert’s way of telling his gymnasts to clear the mats off the floor before making them run laps – would send her into a panic attack, Brittany and her college coach told CNN.

After Brooks started investigating Geddert in the spring of 2014, Jernigan said Geddert reached out to her again, trying to get her to put in writing that he had never said anything negative about Brittany in their first conversation. Jernigan refused.

A month into college, Brittany received a final Facebook message from Geddert. He couched it as “constructive criticism,” but the tone was clear:

“Your disrespectful departure from our program … is simply shameful. Instead of embracing the challenge and instilling some new found work ethic, you ran. Your picture will never hang on the walls of the gym you disgraced.”

[ad_2]

Source link