[ad_1]

SOLOMON R. GUGGENHEIM MUSEUM, NEW YORK, PANZA COLLECTION/©2018 STEPHEN FLAVIN/ARTISTS RIGHTS SOCIETY (ARS), NEW YORK/PHOTO: SALLY RITTS/©THE SOLOMON R. GUGGENHEIM FOUNDATION

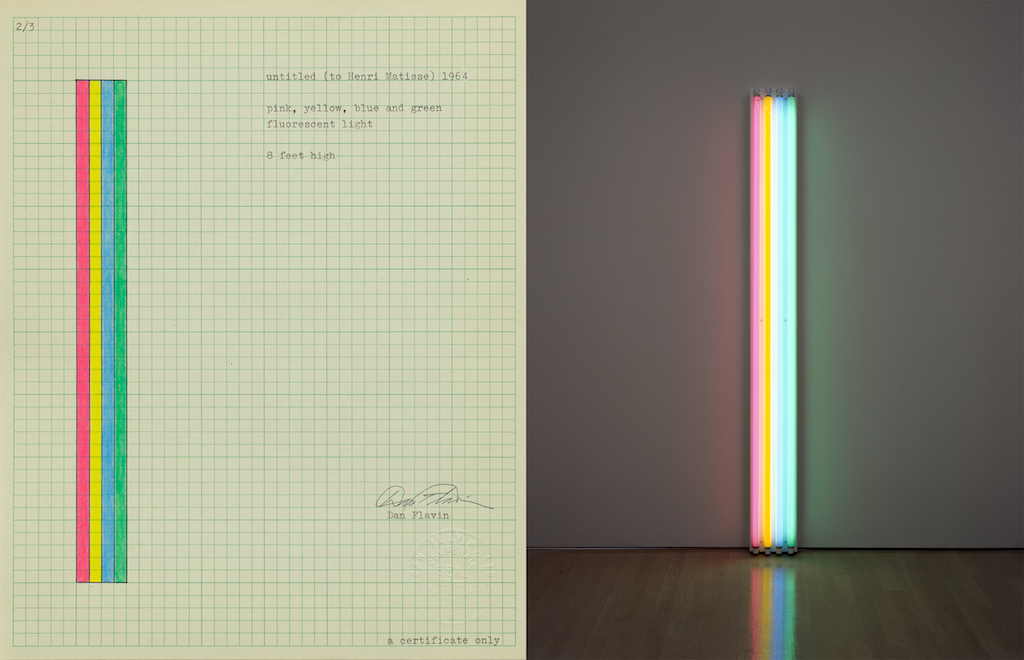

Currently on view at the Guggenheim Museum in New York are two artworks by Dan Flavin—or maybe two halves of one artwork, or possibly zero works if certain considerations come into play. And they’re not really on view so much as on private display for attendees of “Object Lessons: The Panza Collection Initiative Symposium,” a two-day affair gathering a starry cast of curators, conservators, historians, and museum administrators to talk through issues relating to authentication, fabrication, and the overall consideration of Minimalist and Conceptual artworks from one of the most storied collections ever amassed.

There are a lot of issues. As befits a subject that will be taken up by some 25 speakers at the Guggenheim’s all-day panel programs on Tuesday and Wednesday, countless conundrums surround what constitutes the works in question (a certificate? a specific object? a refabrication of an original with new or better materials?), and how best to present them to a public that may or may not care about the finer points of existentialism when looking at art.

“It’s the era of the end of the unique object and the beginning of a period when work was made not by artists but by others—by professional shops, studio assistants, technicians, and other agents assigned to fabricate the work,” said Francesca Esmay, the conservator who—with curator Jeffrey Weiss—has led the Guggenheim’s Panza Collection Initiative since 2010. “In many cases, one work is not identified specifically with a single example. There may be multiple examples, and those examples may have been produced over time according to different standards—at which point the identity of the work itself begins to wobble.”

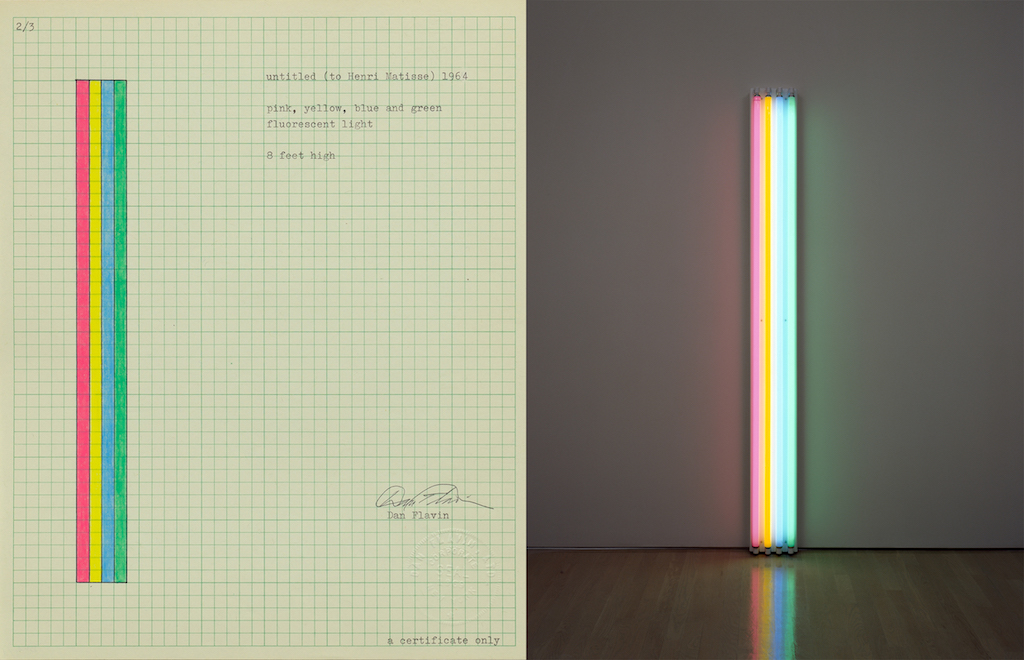

Take Dan Flavin’s untitled (to Henri Matisse), a sculpture involving four fluorescent tubes of light. Two different manifestations are mounted temporarily at the Guggenheim, one dated 1964 and the other 1995. The older one was actually fabricated a few years after Flavin conceived it (the idea for it came first), and the white metal fixture part of it is pockmarked—or, some might say, accentuated—by stickers stemming from its manufacture. “This represents the earlier period of Flavin’s production when the work was still very much rooted in an off-the-shelf philosophy about obtaining art materials,” Esmay said, while making the rounds with Weiss at the museum a couple weeks ago. “The fixture features union labels, and it has accumulated wear-and-tear and little dings—remnants of this actually being a piece of commercial lighting equipment.”

DAVID HEALD/©SOLOMON R. GUGGENHEIM FOUNDATION

Early in his career, Flavin delegated the

fabrication of such works to others—but “there were problems with craft,” Esmay

said. As his practice evolved, the process was refined, and the 1995 iteration

of the same work—with the same color bulbs but with brighter light and a more

pristine fixture behind it—was refabricated in accordance with the Flavin

studio’s custom-production specs. “It’s partly motivated by obsolescence—the

industry starts to shift and it’s harder to obtain this material off the

shelf—and it’s partly motivated by an aesthetic choice of the appearance of the

work,” Esmay said.

To complicate matters further, untitled (to Henri Matisse) was issued in an edition of five, and the artist could elect to refabricate any one of the editions. “Technically the museum should possess one,” Esmay said of the two works illuminated before her. “We have one edition, but we happen to have two iterations of that edition.”

So were we somehow splitting the fabric of

spacetime by staring down the two of them together?

“We are, which is why the project has taken so long,” Weiss said, laughing. “It’s a series of conundrums—what’s an authentic Flavin given this story? As stewards, we have inherited two versions separated by decades that are arguably different from each other, visually and physically, but both of which could be identified as authentic works by Dan Flavin. When you start to apply that overall you get a complicated set of circumstances having to do with whether or not the identity of the work changes over time, which it does, and what we are saying about it historically. It becomes maybe more interesting—or maybe not. But it’s a much more complicated story about what the work really is.”

Questions apply to not just which of the two iterations is ultimately the work itself but also to how to process both, how to archive them, how to assign dates, what to write for wall text when one or the other goes on view, and countless other matters. “We see 14 sides to every story,” Weiss said. “It’s difficult to boil down.”

Even more metaphysically elaborate is Robert Morris’s Untitled (Doorstop), again appearing in two instantiations—one in fiberglass from 1965 and another in plywood from 2018, both of them long triangular wedges that rise up from the ground. “Morris strongly believed in the practice of replication—from his point of view, there was no such thing as an original object,” said Weiss. Unlike Flavin, who died four years prior to the start of the Panza Collection Initiative, Morris worked closely with the Guggenheim before his death late last year to establish parameters for the seeming infinity of questions that attend his work. “The first version of something was simply the first version, not an original to be preserved and valued,” Weiss said. “Over the years, if his work was damaged or he didn’t sell something, he would just destroy it. Under those circumstances, Morris found himself remaking things or having things remade by others.”

The materials often changed too. “In pieces from this period,

some of the first examples were produced in painted plywood,” said Esmay. “Within

a few years, he began to get interested in fiberglass.” At the museum is a fiberglass

iteration made decades ago by the artist himself, with signs of age and

distress that could be seen as markers of time or just distractions that are

entirely beside the point of what Morris had in mind for his work.

ANNE WHEELER/©SOLOMON R. GUGGENHEIM FOUNDATION

“As a historian, I used to think all these works were made at

the time, but it turns out that many of the works I see in photographs from the

’60s were destroyed and then remade over the years,” Weiss said. “In fact, what

I’ve been looking at has been a long sequence of changing fabrications, which raises

the question of authenticity with respect to one object versus another.”

Another important question to keep in mind, Weiss said: “How much does it matter?” Speaking with a mix of excitement and exasperation over the complexities at hand, he said, “We have to always be self-critical and ask ourselves whether or not we’re getting too lost in the weeds.”

In the end, Morris chose for Untitled (Doorstop) to be embodied in the form of painted plywood because fiberglass, as he learned over time, became problematic and overcomplicated to work with and preserve. But the material is less than essential in any case. “Its identity has to be rooted in the idea of the plutonic form and not in the material nature of it,” Weiss said.

Another work nearby, a wooden box by Donald Judd, has an even more peculiar history. First shown at Lisson Gallery in London in 1974, the piece was acquired soon after by Giuseppe Panza, who years later loaned it to the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, where it was instantiated in a different site-specific form. After the second one’s stint on view, the work was dismantled and presumed lost—“because of a lapse in record-keeping,” according to wall text for the Guggenheim display—but Panza authorized a third version five years later in Geneva.

The last one came with a hitch, though: it was not authorized by Judd himself, and thus—though the Guggenheim came to hold its remains—the museum classified the work as “decommissioned.” Until, lo and behold, MOCA rediscovered remains of the second version in 2016, leading to a reversal on the Guggenheim’s part on the question of authentication.

“It’s one of several instances when Panza

and Judd accumulate pretty grave differences in interpretations of what a contract

represents,” Esmay said of Untitled

from 1974.

“A number of works now, long after Judd’s death, exist only in fabrications that he ultimately rejected but which the Guggenheim acquired from Panza, and which belong to the history of his work,” Weiss said. “Since they only exist in rejected form as objects—but, as ideas, live in another place and squarely belong to the practice—as museum stewards, the challenge is how to hold or preserve the work but make sure that in the future that the ‘bad object’—to abbreviate a complicated story—is kept from being shown and falsely representing an authentic Judd.”

Weiss added a point about such holdings

for clarity. “It’s not the case

that we want to delete them—it’s sort of the opposite. We want to find a way to

hold them and retain what’s very valuable about them, which we see as a rich access point for deeper understanding

about the nature of the work.” And the case between Panza and Judd is especially

instructive. “It’s a long story with lots of twists and many cases of—now,

looking back—understandable misunderstanding.”

And as with the works in the historical record of the Panza Collection—and many others like it—Esmay said, “There’s a lot of gray area.”

[ad_2]

Source link