[ad_1]

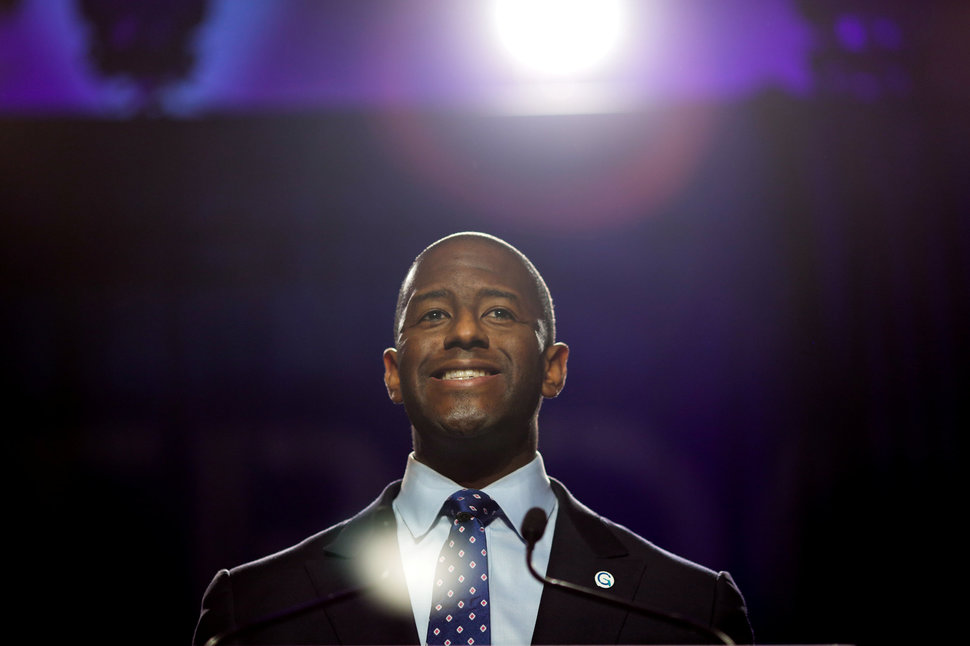

WASHINGTON — This was some black stuff on stage. This was Stacey Abrams, Democratic candidate for governor of Georgia, talking about being of “a very rich brown hue.” And Andrew Gillum, a Democrat running for governor of Florida, whose finances have become a matter of public scrutiny, joking that his complexion was “the only thing I’m rich in.” And Ben Jealous, who is running for governor of Maryland, musing that he had to restrain himself because what he had to say was more fit for a game of spades.

They were at the Walter E. Washington Convention Center for the Congressional Black Caucus Foundation’s 48th annual legislative conference, where the three candidates were keynote panelists in their first public appearance together since winning their primaries. Their session was black in the big things, and it was black in the little things. At one point, a close observer might’ve glimpsed Gillum pointing and popping his hand back in the black semaphore for “I heard what you said, and I agree.”

And the conversation, taking place in a country where most political candidates are white men, was most compelling when the candidates spent 10 minutes talking about the racist attacks on them and their campaigns. It wasn’t just the fact of the attacks; it was the careful calibration required of them in responding to racism.

Benjamin Lowy via Getty Images

Abrams doesn’t assume that every attack from an opponent is racially motivated, but she knows what’s up when she sees it. An August ad from the Republican Governor’s Association attacks Abrams for “dancing around the truth” and shows a pair of tap-dancing feet. The advertisement, which loops the dancing feet in the background while the narrator attacks Abrams’ personal finances, is an ode to minstrel shows, the trope of the simple-minded irresponsible negro and a time when the only form of dance black folks were permitted to learn was tap.

“I know when you have a tap-dancing icon in the commercial against me — you could’ve picked a ballerina. … You picked a tap dancer,” she said. “And there was something implicit in what was done that either calls to what you think or calls to something you haven’t examined.”

Part of the challenge with race is that it factors unseen into many of the decisions people make — including on policy. Abrams cited her desire to launch a $10 million small business financing fund. She laid out how many potential small business owners in Georgia can’t get the loans they need to open businesses since the state lost more banks than any other following the 2008 recession. Most of these banks, she said, were community banks in neighborhoods of color. While her opponent maintains that such a fund is unnecessary, Abrams is thinking about the legacy of race and its role in banking.

Christopher Aluka Berry / Reuters

“We have to talk about this … but at the same time try to hold our people,” said Gillum, picking up where Abrams left off. He noted that he never dismisses the role of race in America, and that in politics “it feels like it’s on steroids.” But Gillum can go only so far in talking about it.

“It’s a line you can’t cross in calling it out because then you call the race card, or you pandered in some way or you’re trying to send some secret signal to somebody,” he said. “Well, so far in my race, it seems that my opponent and some of his friends are the only ones trying to send secret signals. But they’re not so secret.”

Within days after winning the Democratic primary, the racist attacks on Gillum heighted. On Aug. 29, his opponent Rob DeSantis told Floridians not to “monkey this up” by electing Gillum, before going on to refer to him as “articulate.” The next day, robocalls linked to a neo-Nazi group in Idaho began targeting Gillum as well.

“We Negroes … done made mud huts while white folk waste a bunch of time making their home out of wood an stone,” says a man using a stereotypically exaggerated dialect and pretending to be Gillum. Drums and jungle noises play in the background while the speaker maintains that Gillum will pass a law allowing black people to escape arrest “if the Negro know fo’ sho he didn’t do nothin.’” Days later, an Orlando-area GOP official posted a meme that falsely claims that Gillum intends to issue reparations for African enslavement.

Such attacks are why black political candidates have to be careful and “not fall into the trap,” Gillum said.

“My grandmother used to put it this way: ‘Never ever wrestle with pigs because you both get dirty but the pig likes it,’” he said. “I’m not calling my opponent a pig. I’m simply using a figure of speech to say that when we go down into that barrel, if they’re able to make our races — no pun intended — about race, that’s when we can’t win.”

The Washington Post via Getty Images

Black candidates operate in a bind. If they call out racism, they’re accused of playing the race card and responding emotionally to attacks rooted in the denial of their humanity. This gives their opponents significant leverage in a country where many still don’t see race as that big of a deal.

“And that’s the goal of the attacks on all of us,” said Jealous, finishing Gillum’s thought.

While the attack ads on Jealous haven’t been as blatantly racist as those against Abrams — like when she was referred to as a “Bloomberg-Soros Hate America Leftist” — and Gillum, many of them have claimed Jealous is a “socialist” who will “blow a Chesapeake Bay-sized hole” in the state’s economy. Jealous said the goal is to use race as a tool to carve up the electorate, despite the fact that most of the families in his state, regardless of race, voice concern about the same issues.

“But we have to go high,” he said. “And the reason we have to go high is that’s the way that we lead people out.”

[ad_2]

Source link