[ad_1]

Jennifer Packer’s 2017 painting An Exercise in Tenderness represents the summit of painterliness in the Biennial.

MATT GRUBB/COURTESY THE ARTIST, CORVI-MORA, LONDON, AND SIKKEMA JENKINS & CO, NEW YORK/PRIVATE COLLECTION

Like Miles Davis, every Whitney Biennial blows, haute and cool, and inevitably, for some bodies of opinion, that other way too. À la Miles, every Whitney Biennial aims to lend aristocratic imprimatur and coherence to an essentially anarchic field, to reify and revolt against its host body—The Institutional White Art World (henceforth to be referred to as TIWAW)—while functioning as both high-minded survey and gutsy provocation. This year’s Biennial, curated by Rujeko Hockley and Jane Panetta, hits all those conflicted marks. The show should also be read, however, in a context framed by two recent events: a conversation in July in the New York Times on the “25 Works of Art That Define the Contemporary Age” and Open Casket (2016), the last Whitney Biennial’s much fussed-over and mostly disparaged flashpoint painting of Emmett Till by Dana Schutz.

Whether any phenotypically “white” artist should be allowed to dispassionately exploit historic images of murdered and martyred Blackfolk is not a question TIWAW answers without taking the 5th Amendment. What it can do, however, is appoint an African-American woman curator, one whose politics in today’s vernacular are “Blackety-Black,” and then stand back and watch her unapologetically co-curate a Biennial in which women artists of Afro-diasporic descent numerically and ethnically dominate as a group via the inclusion of works by Steffani Jemison, Las Nietas de Nonó, Jenn Nkiru, Autumn Knight, Martine Syms, Wangechi Mutu, Tomashi Jackson, Alexandra Bell, Tiona Nekkia McClodden, Jennifer Packer, Simone Leigh, Janiva Ellis, and Garrett Bradley.

A smattering of Black males, some queer-identified and some not, also figure into the mix, and women of all colors overtly outnumber the dudes. Race and gender in America is all about bodies and numbers—when not about gazes and erasures and what actions are taken by the powerful to address the barbarism of its gates, moats, drawbridges, borders, and concentration camps. Not to mention the industrial warlords among its major patrons and boards of directors—in the Whitney’s case, Warren B. Kanders, whose company, Safariland, manufactures tear-gas canisters used against protesters and weapons used around the world.

An installation in the Biennial by the collective Forensic Architecture is an Op-artful exposé of Kanders and his company’s tear-gas weaponry as well as one of the works that dissenting artists asked to be removed from the show midway between its opening and its close on September 22, all in protest of Kanders’s presence on the Whitney board. (Kanders resigned shortly after in July, and the artists—including Eddie Arroyo, Korakrit Arunanondchai, Meriem Bennani, Nicole Eisenman, Nicholas Galanin, Christine Sun Kim, and Agustina Woodgate—elected to let their work remain.) While certain early-reviewing pundits found the curation’s politics to be radical-lite, perhaps the un-curation threatened by these artists exercising right-of-refusal could satisfy their misread. In any case, given the moving parts at deadline time, we chose to review the show we saw at the start rather than the one that ran the chance of foregrounding righteously and conscientiously gaping holes.

If this Biennial can be said to have a through line, it’s what kind of art gets produced by folk who live in the kind of bodies most subject to physical assault on sight by state-sponsored terrorism—the kind of bodies, and communities of bodies, that have never needed right-wing presidential demagoguery or decree to instruct them daily in the myriad ways that their optics, body politics, and defiant presence on the American scene drive hella American white people (super-wealthy and dirt-poor alike) crazy.

In this regard, the curators pay quiet homage to Mamie Till, the first major Black woman curator to achieve global impact by way of her decision to display her son’s mutilated and bloated corpse in an open casket for world media consumption. “I wanted the world to see what they had done to him” was her battle cry, and that Till, blowing hot and cool, had her son’s body shipped to Chicago rather than buried “down home” in Alabama with the intention of exhibition on her mind is a testament to her revolutionary intellectual process and spot-on futurist grasp of mass-media optics. In nearly a century of anti-lynching protest by various race leaders and organizations, nobody had dared to make a personal statement and political theater out of picturing anti-Black violence through display of a beloved corpse. That no one has since, not even in the age of Black Lives Matter, speaks to Mother Till’s correct presumption that dehumanized Black Corpses Matter more as visual change agents than the postmortem restoration of victims’ humanity seen in family photos.

Simone Leigh’s 2019 bronze sculpture Stick, center, is an icon of weaponized Black femininity.

RON AMSTUTZ

If we take Till as the subconscious curatorial template for Hockley and Panetta’s Biennial, we arrive at a point of convergence with the Times conversation—a very abridged roundtable between artists Martha Rosler, Rirkrit Tiravanija, and Torey Thornton along with curators David Breslin and Kelly Taxter—that untethered itself from defining the “contemporary” in favor of (again, like Miles Davis) defining modern art as something whose faith in transcendental aestheticism ultimately requires contemplation of the blues and cathartic, expressive social bodies to critically justify its existence to the unfree, raced, and transgendered world beyond TIWAW. The back-and-forth provided a timely update of a hoary conundrum: how much art can be squeezed out of our politics, and vice-versa? Gordon Matta-Clark, David Hammons, Jeff Koons, Nan Goldin, and Cady Noland wound up being the participants’ favored subjects for the ripples that their aesthetically driven work made in the social fabric—the “real world” where the messy body politics of real people intersect with those of pristine artifacts.

The majority presence of so many Afro-diasporic female artists is this Biennial’s boldest political statement—and one that, contrary to well-known critics’ dismissive protestations, renders it more than a readily reducible Trump-reactive affair. In this instance, one monkey doesn’t stop or start the show. Not least because today’s Black feminist art-makers didn’t suddenly wake up after election day in a nation where savagely targeting women like them and their communities hadn’t been the acceptable and electable American norm for centuries.

When and where these women enter the Biennial space is as boundary-crossing representatives of a citizen-artist activist tradition that runs from Reconstruction to now. The Latinx and Asian presence on the walls is also noticeable and notable—but nothing signifies the temporary occupation of the Whitney’s defining event by outsiders whose empathies lie elsewhere like the centering of diverse and complex Black women. Or the centering of a diverse and complex white woman’s art in the instance of Nicole Eisenman’s gargantuan marching (and in one case, farting) figures on the sixth floor’s outdoor platform.

This Biennial also features a recurring alignment of communal context and catastrophe, one underscored by Fred Moten’s reminder of the impossibility of talking about blackness—née black existentialism—without talking about Black people as a group. The same could be said of queer artists and non-Black feminist artmakers. The social connection between artists and community demanded by the Times’s consortium provides us with richer tools for apprehension of what’s going on with caste-marked creative individuals.

The photography of Curran Hatleberg exquisitely journals on the quotidian and quixotic communalism of the postindustrial American heartland, a refreshingly un-demonized and de-mythified view of folk in the nation’s dilapidated interior whose adaptation to a futureless environmental dystopia should bear noting by their metropolitan counterparts. Eddie Arroyo’s series of small evocative paintings of a once-fabled Haitian storefront beset by time, rot, and gentrification also addresses the resignation to cultural erasure and devolution that goes on out in the real world where whatever will be will be.

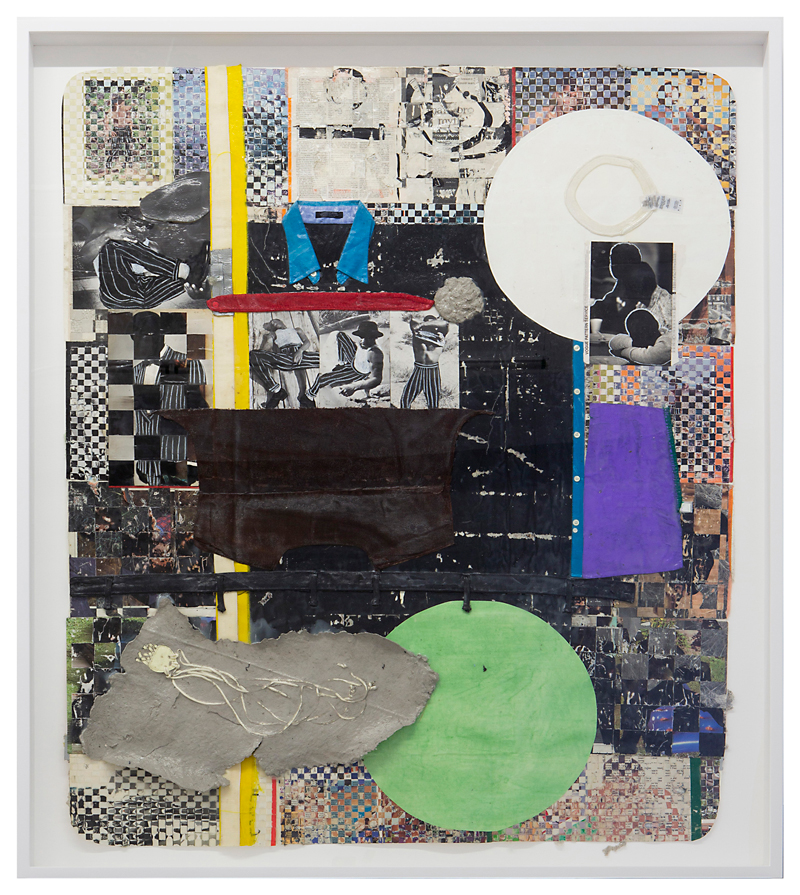

If the show has a formal and living-ancestral/communalist epicenter, it would be the sculpture of Joe Minter, an old Alabama friend and neighbor of Thornton Dial and Lonnie Holley, whose backyard has over decades been transformed into a phantasmagorical found-object theme park filled with playful and expressionist toy-land signposts of protest, oppression, and futurism. Minter’s found-object assemblage extracted and platformed here references Alabama as a police state and the insurgent role played by “foot soldiers of freedom.” Troy Michie’s photo-collage recall of zoot suits as police targets and Tomashi Jackson’s carnivalesque remembrance of Seneca Village, the Black community founded in Manhattan in 1827 and uprooted in 1856 to make way for Central Park, echo Minter’s address of mass-mobilized resistance and vulnerability.

Troy Michie’s 2019 mixed-media photo collage Los Atravesados/The Skin of the Earth Is Seamless recall the histories of police violence in Los Angeles against zoot suit wearers, predominantly Latinx and African-American men.

COURTESY THE ARTIST AND COMPANY, NEW YORK

By contrast, sculptures by Simone Leigh are icons of weaponized Black femininity. The confrontational rage in her work is so visceral and Medusan that it seemed, each time we visited the Biennial, to produce waves of discomfort wherein some white viewers seemed to run-not-walk, without pausing for reflection, through the room where her militantly Afroed and cornrowed pieces are triangulated.

The sumptuous and sensorily overwhelming paintings of Jennifer Packer represent the summit of painterliness in the show, evoking a critique once given to a musician friend by a record exec that there was “too much music in his music,’’ as if bravura technique enthralled to beauty was too distracting for the public. All that’s solid, even effigies of Black lady cops, melts into seductive ephemera in Packer’s hands. The controlled chaos of her strokes is as hypnotic and liberating as that of Basquiat, whose work hers resembles in its lyrical and well-modulated wildness. The artist herself speaks of the work’s intention to project and protect Black female vulnerability, but her improvisational mastery of medium appears just as mission-driven.

Christine Sun Kim’s drawing series Degrees of Deaf Rage in Everyday Situations is all about taking names and kicking asses, those of “audists” (enemies of the deaf) and “terps” (interpreters) who’ve pricked her last nerve enough times to warrant an endless panoply of archetypes and stereotypes. The cool measure of thwarted interpreters taken by Gala Porras-Kim reverses the white anthropological gaze in recognizing the silence imposed by artifacts containing an epi-Olmec language that has resisted deciphering for 400 years. The reliefs that Porras-Kim constructed to support her hypotheses are among the most beautiful freestanding objects in the exhibition.

Porras-Kim shares space with three works by Puerto Rican assemblage artist Daniel Lind-Ramos that obliquely reference in one piece the devastation and abandonment of his homeland wrought by Hurricane Maria and, in another, the legacy of Black resistance to imperialism on the island. A Black woman artist friend thought the tight spatial grouping of Porras-Kim, Lind-Ramos, and vocalist/video artist Laura Ortman tipped toward ghettoization, but it also made her read them positively as a Latinx ensemble. It might not be a bad thing for African-Americans to be repeatedly reminded that the Afro-diasporic histories of post-colonial Caribbean and Latin American folk compel art that does ethnographic contemplation differently.

That bodies of knowledge can be as enslaved as human bodies or even virtual ones rears up as thesis in Martine Syms’s multi-work installation, in which a virtual avatar twirls and dances, publicly and privately, in dialogues about making a threat assessment of her free Black female body in liberated and repressive social space. Steffani Jemison’s video work Sensus Plenior (2017) is a recommended must-see for the ghost imagery she conjures out of the otherworldly performance of gospel mime minister and choreographer Susan Webb.

John Edmonds’s elegant and evocative series of photographs of millennial Blackfolk in intimate contact with African masks, statuary, and fabrics presents romantic takes on ancestry, reclamation, and more.

RON AMSTUTZ

John Edmonds’s elegant and evocative series of photographs of millennial Blackfolk in intimate contact with African masks, statuary, and fabrics presents romantic takes on ancestry and reclamation, spirit possession, and even enchanted trans fantasies of motherland maternity. The dicey conflation of modernity and primitivism in TIWAW is aesthetically evoked and dangled in his works in ways that also speak to the newfound embrace of carved African things prompted by the anti-colonialist rhetoric inscribed in the storytelling of Black Panther.

The paintings of Pat Phillips reference the infamous prison/neo-slavery plantation in Angola, Louisiana, and twist and knot that history with the racist paranoia of white nativists who have chosen “Don’t Tread on Me” as a motto for their fear of ethnocide—a neurosis that belies the numbers of African-American males under lock and key in the prison-industrial neo-slave system. A fang-baring snake ensnaring dismembered prison-striped limbs makes Phillips’s Mandingo/DON’T TREAD ON ME (2018) the most gut-churning and expressionist work in the series.

The monstrosity of many scary things being born in the present political and cultural moment is best captured in the show’s exhibition of Heji Shin’s 2016 “Baby” photographs. In serving up infants’ mushy heads at the bloody moment of birth, crowning out of splayed vaginas, you feel as if Shin is providing a vision of basic reproductive biology as anti-Christ theology—a frightful premonition and shaping of things to come that resonates with as much bruised innocence as gallery art can offer our battered radical psyches at this time.

A version of this story appears in the Fall 2019 issue of ARTnews, on newsstands September 24, under the title “Display Cases.”

[ad_2]

Source link