[ad_1]

By George Kevin Jordan, AFRO Staff Writer

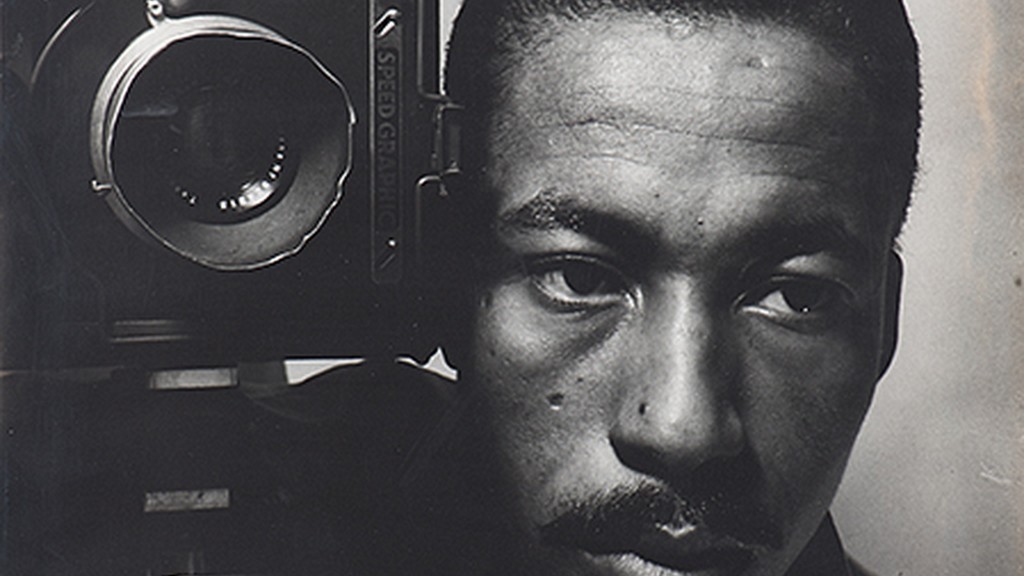

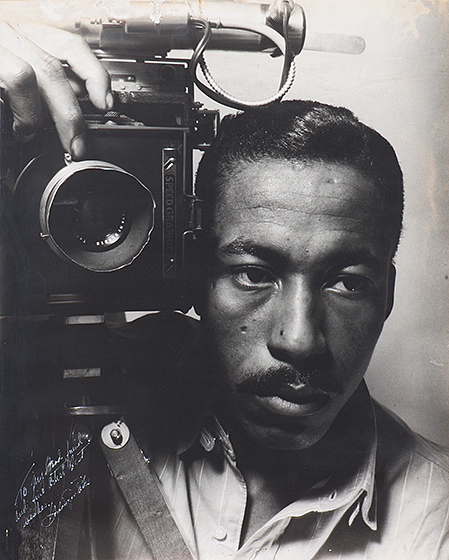

Gordon Parks has left an indelible mark on Black and the broader contemporary culture.

Born in Kansas in 1912, the renowned photographer documentarian, filmmaker and author has created works that challenged the stereotypical narratives of Black culture that mainstream media sometimes portrayed. For him, the camera was his weapon against racism.

And, with works spanning over 60 years, Parks’ influence was pervasive. Some may know him as the first African-American man to write and direct a film (“The Learning Tree.”) Or, more likely, his name comes to mind with mention of the blaxploitation classic “Shaft,” which he directed. He won several honors and awards and was active until his death in 2006.

Parks also had an illustrious career as an editorial and fashion photographer for Ebony and Life magazines, among others, breaking down racial barriers and showing the often neglected glamorous side of Black people.

This winter, however, visitors to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., will get to see a less-publicized aspect to his career—its beginnings.

“Gordon Parks: The New Tide Early Work 1940 – 1950” is an exhibit that offers a glimpse into the process and vision of an artist whose work influenced several generations of people, but who was, once, simply a young man with a camera learning his craft.

The title of the exhibit is taken from a phrase that “Native Son” author Richard Wright inscribed in a book for Parks: “One who moves with the new tide.” Wright was passing the baton to Parks, and new exhibition bears witness to how the photographer first chose to carry out that mission.

“While Gordon Parks’s varied career and influential oeuvre have been well noted and cataloged, the foundational first decade of his life as a photographer has never before been explored in such detail as it is in this rich exhibition and volume,” said Earl A. Powell III, director of the National Gallery of Art, in a press release.

The exhibit is part of a collaboration between the NGA and the Gordon Parks Foundation, and was curated by Philip Brookman, consulting curator in the NGS’s department of photographs.

The exhibit is clustered into suites or periods in Park’s professional life. One of the most influential periods seems to be his time in Chicago and New York, where he was surrounded and influenced by that era’s most significant Black artists, including Langston Hughes, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison and Charles Wright.

In many photos, it is clear Parks is finding his voice, experimenting with light, lines, shadow and composition.

The exhibit shows his soft spot for highlighting the universal joy and heartbreak of the Black youth in America. Photos of Black children are sprinkled throughout the exhibit, many smiling, finding joy no matter the circumstance. Other images, however, take a less varnished approach, pulling back the lens to see the conditions in the urban meccas such as Chicago, Harlem and D.C. that many young Black people called home.

One of Park’s most enduring and powerful works was his American Gothic collection and, particularly, “Washington D.C. Government Charwoman” taken in 1942 while Parks worked for the Family Security Administration’s (FSA) photo unit. The photos shows a worker named Ella Watson. The image is still striking and also made more relevant when positioned next to the larger collection, where the audience gets to see Watson’s family. The exhibit goes into more depth about the process and purpose of each of the photos.

The exhibit, which is free and open to the public, runs through Feb. 18, 2019. For more information please contact the Gordon Parks Foundation or The National Gallery of Art.

[ad_2]

Source link