[ad_1]

Illustration by Scott Chambers.

While ageism is prevalent in Western society, it’s not exactly a frequent topic of discussion in the art world, despite repeated cases of elder abuse. There’s the alleged financial exploitation of artists Robert Indiana, Stan Lee, and Peter Max, and surely others that have gone under the radar. Our two discussants this month address the elusive issue head-on. Dutch artist Lily van der Stokker makes wall paintings that feature curlicues and flowers in both bright and pastel colors, often accompanied by short, sweet phrases—sometimes with a biting edge. (When filmmaker John Waters interviewed her in 2003, he compared them to doodles made by a teenage girl.) Van der Stokker has been using these girly, jejune visual motifs for forty years, focusing on topics like gender, care, and domesticity, but her two most recent exhibitions—which were on view last year at Kaufmann Repetto in New York and the Migros Museum in Zurich—centered on the process of aging. The US-based scholar Lieke van Heumen—a gerontologist who also happens to be Dutch—spoke with van der Stokker about her work by video chat in February. The two discussed taboos and misconceptions around the experience of growing old.

Lily van der Stokker Are you a millennial?

Lieke van Heumen I am.

Van der Stokker I’m a baby boomer. There is a lot of press about how millennials and baby boomers are mad at each other . . .

Van Heumen You are the same age as my mom: sixty-five. I really believe that we need to have solidarity across age groups in our communities, and to find ways to respect each other’s differences.

Van der Stokker Recently in Holland, millennials published articles suggesting that the government should take away voting rights from older people. They assumed baby boomers were not interested in protecting the environment. That made me so angry.

Van Heumen Were you thinking about solidarity when you titled your Migros Museum show, “Help help a little old lady here”?

Courtesy Feature Inc., New York.

Van der Stokker I chose that title because it is funny. I made a drawing with that text in Dutch in my studio one afternoon, and both my assistant and my boyfriend had a laugh.

When I decided to make the image into a wall painting, I was aware that visitors would probably assume that the old lady is me, the artist, though I wasn’t thinking about myself when I made it. I admit that I am probably considered old, though my everyday life is mostly the same as it was when I was thirty-five.

Society looks down on older people, especially sick ones, so in this artwork we are confronted with our own prejudices. An old lady asking for help twice (help, help!) in a childish way is funny, but I think that old people are sometimes ashamed of being needy.

Van Heumen Older people are often not taken seriously. This means the elderly are rarely asked what their needs and preferences are: other people try and make decisions for them, assuming that they cannot do so on their own. I’m working on finding different approaches to elder care.

Van der Stokker I find it shocking that older people are so often the butt of the joke: I see teenagers that make fun of the elderly who need big, super-legible numbers on their phone. I don’t think that’s going to change very soon, even though there are a lot more old people these days.

Van Heumen The percentage of the world’s geriatric population has doubled since 1980, and is expected to double again by 2050.

Van der Stokker Why do you think people make these jokes? I assume they make them more because they are afraid of the diminishment that comes with old age, rather than because they are disrespectful.

Courtesy Hammer Museum, Los Angeles/Photos Brian Forrest.

Van Heumen I’m optimistic. You’re saying you don’t think things will get better, but I hope to help change ageist and ableist attitudes in society by educating people and raising awareness about our unintentional biases, about the ways we treat each other. I talk about these sorts of issues with my students in a course I teach called Disability in US Society.

Van der Stokker But when you say “disability,” do you mean people who have been disabled their whole life?

Courtesy Hammer Museum, Los Angeles/Photos Brian Forrest.

Van Heumen Not always—plenty of people become disabled later in life.

Van der Stokker You mean like with dementia?

Van Heumen Sure. But not everyone thinks of dementia in a disability studies framework.

My research focuses on the intersections of aging and disability. Right now, I’m working to understand the unique care that people born with intellectual disabilities need as they age. It used to be that people who were born with intellectual disabilities rarely lived into old age, but that’s not the case anymore.

Van der Stokker My life partner, Jack, and both of my parents died from dementia. I wish I never saw that, but I did. My neighbor likes the saying, “getting old is not for sissies.”

I certainly see a taboo around aging: older people are often seen as losers. Sickness is taboo too: I notice that some people hide their sickness. Their attitude is: no complaining. Be tough, fight the disease.

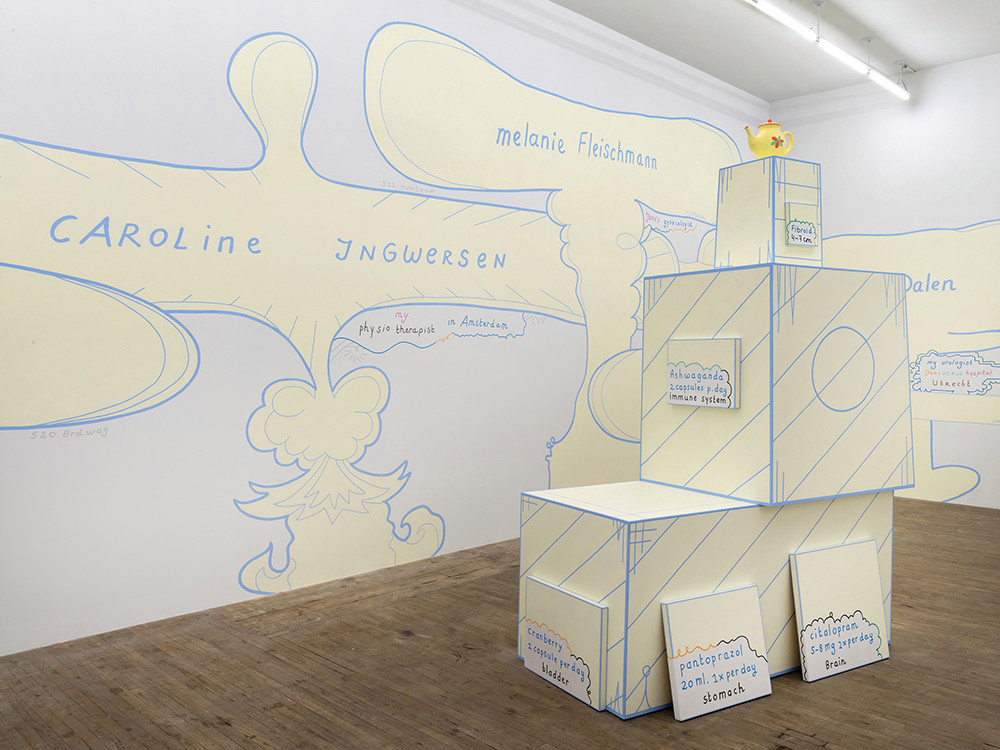

I did the opposite in my show “Exhibition of the Medicines” at Kaufmann Repetto in New York. When people came into the gallery, I would lightheartedly point to Lymphoma, a wall painting that also references prostate cancer, and say: “Here you see the deadly diseases!” Then I would point at the large wall painting [Age 65.75] and say: “And here you see the names of all my health-care practitioners, along with the body part they treat.” After that, I’d point at a sculpture with a teapot on top called Washing Machine (object with teapot) and say: “And there you see all the names of the medicines and food supplements that I take.” It was a difficult subject matter, but we had lots of visitors and some people were very touched by the show.

Van Heumen It’s really important that we talk about these everyday experiences as our population continues to age. I sometimes use visuals in my research, when working with older people with disabilities. Some of them have limited verbal ability, so visual modes of communication are often very useful for them to express their life experiences. But in your visuals, you’re still using a lot of text. Why did you include details like your healthcare practitioners?

Van der Stokker I did that to bluntly confront the visitor with the banality of the subject matter. Nobody is interested in hearing unimportant names of somebody’s doctors and nurses; it’s useless information—though my gallerist joked that I should put their rates and leave a review on the wall! Nevertheless, all of us have some similar health-care experiences. I see the work as recording the reality of people my age. All of my peers, friends I still know from childhood and art school, have various illnesses now: some chronic, some deadly. It’s really scary, but we have no other choice than to deal with it.

All of the information in “Exhibition of the Medicines” is true and mine: there needs to be some truth to make it juicy, to make it touch people. But really, it doesn’t matter that it’s about me. Some people thought I made the exhibition because I was diagnosed with some deadly disease, that it was confessional art, but it’s less spectacular than that.

I wanted to portray everyday life: a physiotherapy appointment, a cold, a bout of flu, my bladder medication.

Courtesy Migros Museum für Gegenwartskunst, Zurich/Photo Stefan Altenburger.

Van Heumen Looking at the paintings, I see the types of support networks that many of us rely on, especially as we grow older. Care is banal and everyday, and as you say: unspectacular. But this doesn’t mean that it’s unimportant. Today, in Western culture, we place a high value on autonomy and independence; we forget that, in reality, we all depend on each other in our everyday lives. Dependency is often associated with weakness and shame, which I think is part of why care labor, usually performed by women, is often unpaid or underpaid. You’re showing respect to these health-care workers by putting their names on the wall.

Van der Stokker When I made The Tidy Kitchen [2015] at the Hammer Museum in LA, I was celebrating domestic tasks. Some people thought that this wall painting, which was about washing and cleaning and tidying, was a complaint. On the contrary: in this work, I was supporting and highlighting women, and also men, who clean and take care of our houses and our messes, because people do look down on these traditionally feminine tasks.

Van Heumen Can we talk about young people? Or are we the bad guys?

Courtesy kaufmann repetto, Milan and New York/Photos John Berens.

Van der Stokker The art world needs the energy and new ideas of young people. Still, I find it sad that, when artists get older, they cannot be considered avant-garde any longer. Most older artists are not taken as seriously as they once were. A few are said to make their best work at the end of their lives, but most not.

For my show at the Migros Museum, I made a wall painting about this issue titled Extremely Experimental Art by My Grandma [2019]. It was a big piece—around forty feet long—and I redesigned it several times because I was not, and am still not, satisfied that it is experimental enough. I first made a series called “Extremely Experimental Art by Older People” in 1999 and 2000. At the time, I was forty-five and thinking about my future.

I already thought I was pretty old!

Making work about oldness is a bit taboo in the art world: once you’re no longer young and fresh, you’re not as much part of the art discourse anymore. Nowadays, however, maybe I do want to slow down. Maybe I don’t want to participate in the hype around the newest cutting-edge development, but instead want to reflect on all I did over the last forty years. So I enjoyed imagining a peculiar grandma making extremely experimental art. For me, the work was an alibi to happily create something weird and ugly. The work is tongue-in-cheek and confronts us with our own tendency to discriminate against the old.

—Moderated by Emily Watlington

[ad_2]

Source link