[ad_1]

ATLANTA ― Gwinnett County, Georgia, is one of the most diverse counties in the country, but you wouldn’t know it from the houses on this particular block. Aside from a couple of political signs and the occasional overzealous Halloween decorator, this street in the city of Duluth is a stretch of similar two-story cream-and-brick homes, all facing similarly well-manicured lawns.

On a Thursday in October, six black women wearing bright orange T-shirts and jeans pull into this squeaky-clean north Atlanta suburb just before sundown, after what should have been a half-hour drive from the city took more than twice as long in traffic. They are domestic workers by day ― nannies, housekeepers and home care workers ― but they spend their evenings knocking on doors for Stacey Abrams, who would be the first black female governor in the history of the nation.

The plan is to skip over the houses inhabited by white people and target the voters of color. The women have a canvassing app, MiniVAN, that helps them to know which are which. Just over half of this immigrant-heavy county is non-white, but they are rare and sporadic voters ― so turning out the vote here could be crucial to Abrams’ election in what is now a razor-thin race against Republican Brian Kemp.

The work can be dangerous, so the women always keep each other in eye-shot while canvassing. Occasionally their app fails them, and they encounter a house with a Confederate flag or some other white supremacist symbol. Sometimes there’s a run-in with their fellow Georgians — an older white couple, for instance, backing their white Ford pickup out of their driveway and pulling up next to the women I’ve accompanied today. A Kemp sign pokes out of the couple’s yard in the distance, and a large German shepherd pants in the backseat. The wife rolls down her window and asks the women what they’re doing there, while the husband snaps pictures of one of them and the license plate of their car.

Shechel Williams, a gregarious 45-year-old home health aide, warmly explains that they are domestic workers campaigning for Abrams. She hands the wife a flyer through the window, and the suspicious couple speeds off without saying much.

The canvasser who just had her picture taken, Nilaja Fabien, is a 46-year-old Trinidad native who has spent nearly three decades working as a nanny for white children in Atlanta. She wears a blue denim cap over her closely cropped hair and speaks softly and deliberately, as if she’s leaning over to tell a secret in the library. She is momentarily shaken by the encounter with the white couple.

Laura Bassett/HuffPost

“What in the world?” she asks.

“You know what’s in this world,” retorts Williams. “Just people trying to scare us.”

More than 300 domestic workers in Georgia ― nearly all black women, plus two men ― are running the largest independently funded ground game in the state ahead of this historic election. Their organization, Care in Action, is the political arm of the National Domestic Workers Alliance, which represents 2.5 million domestic workers across the country. They’re talking to voters of color in four critical counties, from the Atlanta suburbs to rural southwest Georgia, that could feasibly turn from red to blue if more non-white voters showed up at the polls.

While the proximate goal is getting Abrams elected, the domestic workers’ efforts are a continuation of an activist movement that began in earnest at the midpoint of the last century. For the most part written out of the popular history of postwar social movements, domestic workers, in fact, were a driving force in the fight for labor and civil rights. They played a central, if largely invisible role in the Montgomery, Alabama, bus boycott in 1955 and 1956. “Beginning in the 1960s, household workers organized forums, spoke publicly, circulated pamphlets, gave testimonials, and lobbied legislatures,” writes Premilla Nadasen in Household Workers Unite. What began as “a grassroots movement of domestic workers,” Nadasen adds, “evolved into a mass movement which fundamentally redefined black women’s relationship to the world of work.”

“Yes, we want to get Stacey elected, but it’s not just about getting a person elected,” says Nikema Williams, a state senator and the Georgia state director of Care in Action. “It’s about reclaiming our power, reclaiming our voice and making sure that our issues are uplifted, because we are living these issues every day as women of color here in the South.”

Abrams’ platform would directly and indirectly improve the lives of domestic workers. She’d expand Medicaid; she supports requiring a living wage across Georgia, instead of the current $5.15 an hour minimum; she has a plan to reintegrate incarcerated people into society and guarantee access to quality public education for all children. She wants to expand broadband access and better transportation to rural and low-income communities across Georgia, to better incorporate them into the economy.

These are important issues for domestic workers because women of color “are typically on the chopping block for everything,” Williams says. “When things are being cut, we are at the bottom of the totem pole. So we are being very intentional about standing up for the people that identify as domestic workers because care work allows every other work to be possible.”

Williams, 40, led the canvass I observed in Gwinnett County on Oct. 18. She’s a champion for Abrams, but she’s also part of the post-Donald Trump wave of new women candidates herself. In December, she became the first woman elected to the historic Atlanta seat in the Georgia state legislature that was occupied by civil rights leader Julian Bond in the 1960s. She joined Care in Action in June to galvanize other women of color.

“I definitely felt like my voice was needed in this conversation,” she says. “After the 2016 elections, there were a lot of white women that stepped up and found their voice and started their movements and their Facebook groups. And black women are the base of the base. I was like, if not now, then when? And if not me, then who? So I went for it.”

‘A Chubby Ass To Whip’

Abrams is the first candidate Care in Action has ever endorsed ― a fitting first sally into politics, since the domestic workers’ movement began in Atlanta. Back at the group’s headquarters there, a framed photo of Dorothy Lee Bolden hangs on the wall. A neighbor and friend of Martin Luther King Jr., Bolden founded the National Domestic Workers Union in 1968. In the photo she’s wearing cat-eye glasses, hair piled high on her head, and she’s flashing a peace sign to a crowd on stage after apparently giving a speech. She’s surrounded by men.

Beneath the poster, her quotation sits in a frame: “We aren’t Aunt Jemima women, and I sure to God don’t want people to think we are. We are politically strong and independent.” On the wall nearby are two posters of the Georgia House and Senate Labor Committees, with pictures of the mostly white men who sit on them ― a potent reminder that the fight Bolden started is ongoing.

The canvassers are all well-educated on the history of Bolden’s advocacy. One of six children, Bolden began washing diapers after school in 1930, at the age of 9, for $1.25 a week, and then cleaned house for a Jewish family for $1.50 per week at the age of 12. In 1940, she was hauled off to county jail and given a psychological evaluation for having refused the demand of her boss, a white woman, to stay late and wash the dishes. “She had come to believe that poverty and economic deprivation were critically important” to the goals of the civil rights movement, Nadasen writes, “and that you couldn’t integrate schools if children didn’t have shoes to wear.”

Bolden began to learn about activism and organizing from King in the early 1960s. She had 10 children, three of whom died in infancy, and her first organized activist experience involved fighting for their equal education rights. In 1964, the Atlanta School Board sought to move her kids’ all-black school to a condemned building, and Bolden led the protest and boycott that ultimately stopped that from happening.

That same year, after riding a bus with other housekeepers and hearing their complaints about low wages, long hours and racism on the job, she decided to organize Atlanta’s maids to fight for better working conditions. She conducted voter registration drives for domestic workers and educated them in the tactics of the civil rights movement. In 1968, with the consultation of representatives of the organized labor movement, she called the first meeting of the National Domestic Workers Union. For membership, people only needed a dollar and a voter registration card.

The union managed to defeat the first referendum to fund MARTA, Atlanta’s public transportation system, in 1968 because it hadn’t included black people in the planning. Under Bolden’s charismatic leadership, domestic workers became a powerful union across 10 states, raised Atlanta’s wages by 33 percent and won the inclusion of domestic workers in workers’ compensation and Social Security benefits.

Three presidents in the 1970s consulted Bolden on issues affecting workers, and President Richard Nixon appointed her to an advisory committee on welfare and social services. “I was the only Democrat up there,” she told the Atlanta Journal-Constitution in 1986. “I was the one that went up to Washington to kick up some hell about women not getting the attention they deserved.” She led the National Domestic Workers Union until 1996, often in the face of racist harassment. As Nadasen recounts, Bolden once got a phone call from a Ku Klux Klan member who threatened to “whip her ass.” Bolden’s response: “I told them any time they wanted to, come on over and grab it. You’ve got a chubby ass to whip.”

“She didn’t back down to anybody,” says Williams. “She stood up to make sure workers had contracts and base wages, some of the same things we’re fighting for today, just to have dignity and to be heard in order to do their jobs. We absolutely ground ourselves in the work of Dorothy Bolden and her vision in everything that we do.”

‘Yeah, Girl, Did You See “The Help”?’

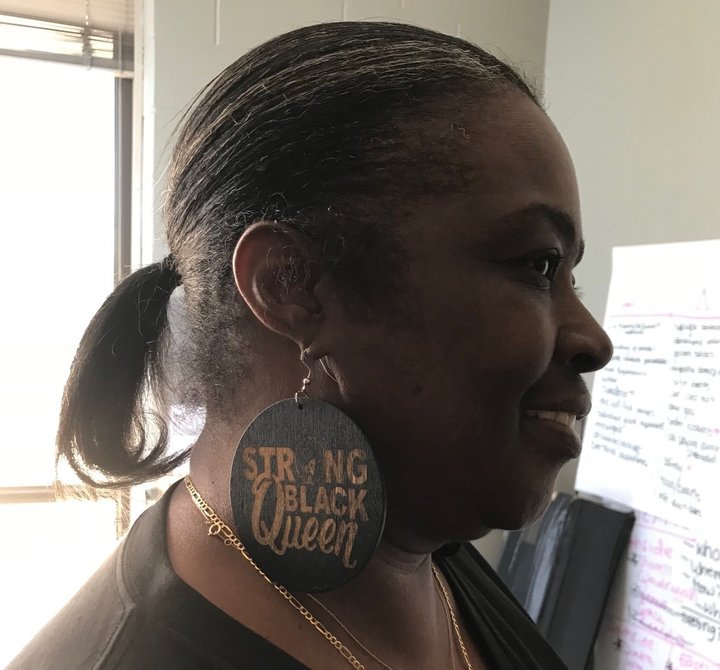

Around 3 p.m. every day except Sunday, more than a dozen women gather here at Care in Action’s headquarters to share dinner on paper plates, catch up with each other and prepare for the evening’s phone banking and door knocking. “We’ll see if I feel like talking to people today,” Diadra Nelson says with a wink as she strolls in. She is a retired 59-year-old sous chef at the Georgia State University bookstore, and she wears giant round earrings that say, “Strong black queen.”

Laura Bassett/HuffPost

The NDWA recruits these women in parks, bus stations and other public places. Domestic workers are easy to spot, Williams explains; they’re the ones carrying cleaning supplies on the bus in the middle of the day or pushing strollers with babies that clearly aren’t their own.

Fabien was approached at a Barnes and Noble in 2011, where she had brought the two white children she cared for at the time. She remembers that it was right around the time “The Help” came out, because nannies in Atlanta had been talking about the film adaptation in which black housekeepers in 1963 speak out to a journalist about the racism they faced on the job. The movie’s lighthearted portrayal of the civil rights movement and its white heroine narrative flow out of broader, offensive myths about domestic workers, but Fabien says it sparked an important conversation nonetheless.

“It was a huge mobilizing factor from what I saw,” she says. “When I spoke to other nannies about coming to the first meeting, they were like, ‘Yeah, girl, did you see ‘The Help’? It was on the lips of everybody, and they saw the importance of organizing and supporting each other.”

Abrams’ candidacy in Georgia comes at a time when women of color are undeniably winning difficult elections for Democrats in the South. Sen. Doug Jones (D-Ala.), for instance, defeated Republican Roy Moore in a special election last year thanks mostly to the turnout among black women.

But their organizing is especially critical in Georgia right now, where Kemp has been caught engaging in multiple attempts to suppress the black vote. Earlier this month, a report from The Associated Press found that over 53,000 voter applications in Georgia ― nearly 70 percent of them from black people ― were being stalled in Kemp’s secretary of state office, which oversees elections. And Kemp denies being part of a plan to shut down seven polling places in a majority-black area. But Rolling Stone reporter Jamil Smith recently obtained audio of Kemp saying that Abrams’ voter turnout operation “continues to concern us, especially if everybody uses and exercises their right to vote.”

Georgia is not used to seeing women of color on the ballot for governor. The state has always been run by white men ― mostly Democrats until 2002, when then-Gov. Roy Barnes (D) led a successful effort to remove the Confederate battle cross from the state flag. Republican men have won every election since.

The GOP is still hoping to capitalize on that same anger over the state flag to galvanize a subset of white voters who are enraged at the idea that their “heritage” is being erased. The night before the Abrams-Kent debate this week, a photo surfaced on social media of Abrams participating in the burning of the old state flag in 1992, during her senior year at Spelman College.

Abrams defended having joined the “permitted, peaceful protest against the Confederate emblem in the flag,” while Kemp’s camp declined to comment. But Kemp has pledged to protect other Confederate monuments in Georgia, arguing that Georgians should not “attempt to rewrite” the past by removing them.

Laura Bassett/HuffPost

Fabien is more than ready to move on from the state’s racist history. “I feel like the time for that is over, that scary life that they want to have people living right now, that’s done,” she says. “We’re tired of it.”

In this racially charged climate, it would be an enormous relief for women of color in Georgia to see someone running the state who looks like they do and understands their lives. Williams says when she first read in the newspaper that Abrams would be the first black woman governor in the country, she was “in tears.”

“Because I knew that I don’t remember ever knowing a black woman governor in the country, but I just never thought about it,” Williams says. “Seeing it in print, it just gave me chills.”

Abrams grew up poor in Mississippi, one of six children to a mother who worked as a librarian and a father who worked in a shipyard. She went on to graduate from Yale Law School but is still $200,000 in debt from student and credit card loans. As a single woman, she became the first black woman minority leader of the Georgia State House of Representatives, and she writes romance novels on the side. Her brother struggles with drug addiction and has been in and out of jail.

When Abrams talks about reducing student debt, or expanding access to substance abuse treatment and mental health services, or rehabilitating incarcerated people, she is speaking about those issues from experience.

Denise Small, a 50-year-old retired nurse who now cares for an elderly family member, says she trusts Abrams for that reason. “When she talks about these issues, it’s not only on her mouth, it’s in her heart. Her agenda for revamping the criminal justice system, mental health care, it’s just all valid and all necessary.”

Small is about to knock on another door when I ask her if she thinks Georgia is really ready for a candidate like Abrams.

“Oh, hell yeah,” she says. “I think it’s time. Because the people that practice humanity in this world, they’re looking for someone who’s looking out for them.”

[ad_2]

Source link