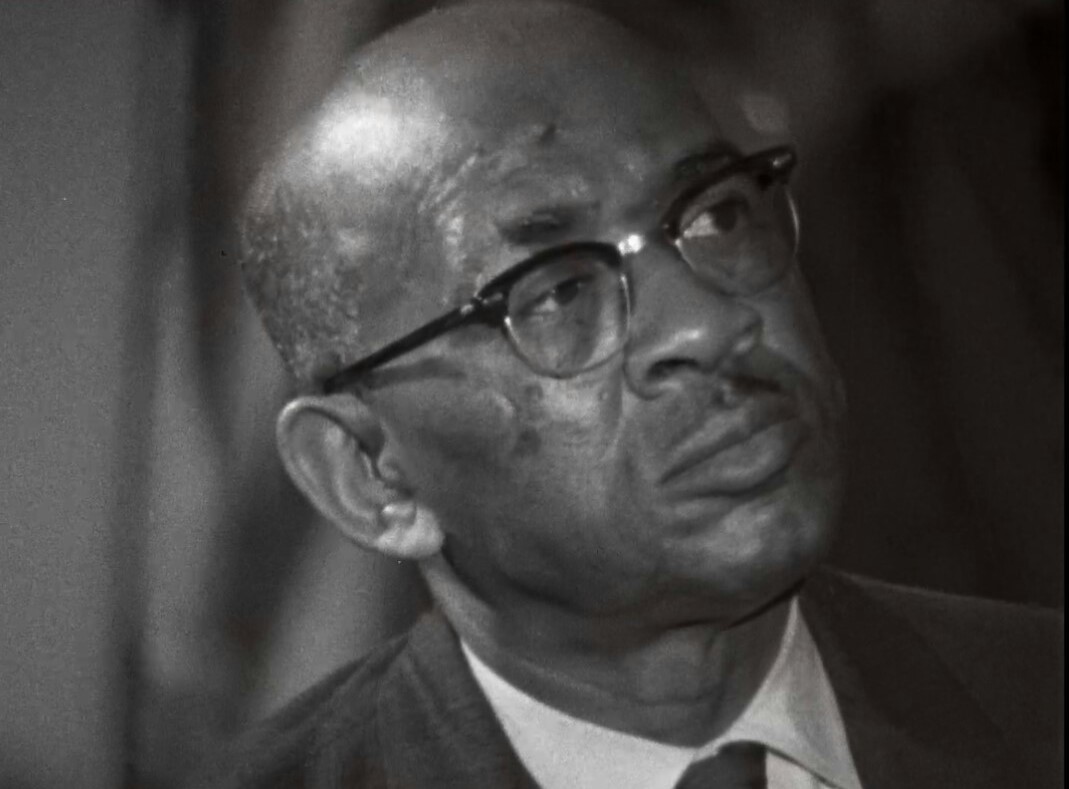

George Metcalfe was a civil rights leader in Natchez, Mississippi who led one of the most successful yet little-known movements in the Deep South.

Metcalfe was born on September 20, 1911, in Franklin, Louisiana to parents Ernest Metcalfe and Alberta Simon Metcalfe. He was a World War II veteran who held numerous jobs leading up to his work with the NAACP. He and his wife, Adell, moved to Natchez around 1940, where he worked as a truck driver for a sawmill. Metcalfe also sold burial insurance and made additional income from his rental property. In 1954, he met Wharlest Jackson Sr. and both of began working that year at Armstrong Tire Company. Metcalfe was a forklift driver and shipping clerk for the company.

Natchez was a hotbed of Ku Klux Klan activities in the early 1960s. Although many Klansmen worked at Armstrong, their presence did not deter Metcalfe from his determination to help the Black community.

Metcalfe lived in a house at 9 St. Catherine St., which was originally built and owned by Dr. John Bowman Banks, Natchez’s first Black physician. During the Freedom Summer of 1964, Metcalfe housed civil rights activists and the home became known as “Metcalfe’s Boarding House.”

Metcalfe’s work made him a target of the Klan. In late January 1965, night riders fired shots into his home. In March 1965, Metcalfe relaunched the Natchez branch of the NAACP with help from Charles Evers, the brother of slain Mississippi NAACP field secretary Medgar Evers. Metcalfe was elected president, and Jackson, secretary.

Metcalfe successfully led a voter drive that resulted in over 8,000 African Americans registering to vote. He and the NAACP called on the Natchez city administration to denounce white supremacist groups like the Klan and to end police brutality. They also urged the city to hire Black employees and to desegregate swimming pools, parks, and other public facilities.

At Armstrong, Metcalfe and Jackson succeeded in having employee promotions based on seniority and qualifications instead of race. Metcalfe also led a delegation which confronted the school board with a signed petition calling for the desegregation of the public school system.

On Friday, August 27, 1965, George Metcalfe completed his shift around noon at Armstrong and walked outside the plant to his 1955 Chevrolet sedan. When he placed his key in the ignition and turned the switch, the car exploded. Metcalfe suffered burns and a broken arm from the explosion. His right leg was shattered in three places and his right eye was permanently damaged. Many, including investigators, believe the bomb was planted by the KKK. However, no one was ever charged for the crime.

In December 1965, the city of Natchez conceded to the demands of the NAACP. Metcalfe, however, spent a year recovering from his injuries and eventually returned to work at Armstrong, alongside the Klansmen, including the leader who ordered the bomb attack.

After he recovered from his injuries George Metcalfe moved back to Monroe, Louisiana and died unexpectedly on April 21, 1989, in his home. He was 77.

Do you find this information helpful? A small donation would help us keep this available to all. Forego a bottle of soda and donate its cost to us for the information you just learned, and feel good about helping to make it available to everyone.

BlackPast.org is a 501(c)(3) non-profit and our EIN is 26-1625373. Your donation is fully tax-deductible.

John Dittmer, Local People: The struggle for Civil Rights in Mississippi (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1995); Lance Hill, The Deacons for Defense: Armed Resistance and the Civil Rights Movement (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2004), and Stanley Nelson, Devils Walking: Klan Murders along the Mississippi in the 1960s (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2016).