[ad_1]

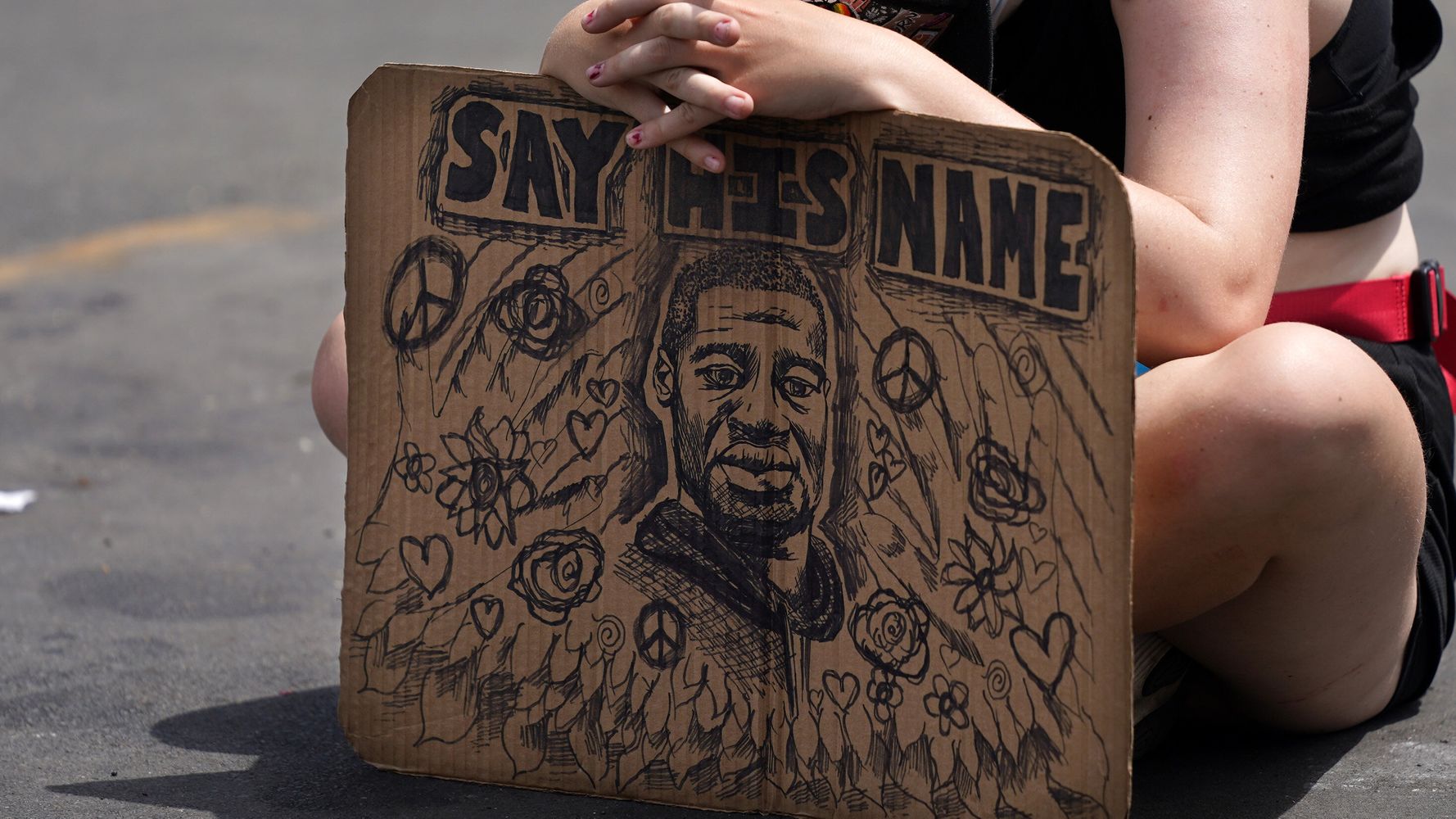

At the beginning of April, George Floyd contracted the coronavirus. It’s unclear how severe his case was and if he struggled to recuperate, but he did recover. He survived one possibly fatal threat, only to succumb to another: the Minneapolis police.

Floyd, a 46-year-old Black man who leaves behind three children, was killed after a police officer knelt on his neck for nearly nine minutes. He had recently lost his job at a restaurant due to the COVID-19 outbreak and was accused of using a counterfeit bill to buy cigarettes when a store clerk called the cops.

The medical examiner, who deemed Floyd’s death a homicide “caused by asphyxia due to neck and back compression,” confirmed in his autopsy this week that Floyd had tested positive for COVID-19. Although the coronavirus was present in Floyd’s system, the report stated, it does not necessarily mean he was contagious at the time he died, and the virus didn’t have an impact on his death.

But it does illustrate a sad, glaring truth: the Black community is facing a multitude of fatal threats. Some of these threats are new: the coronavirus has disproportionately affected the Black community. Some are as old as the country itself. As is often the case, economic turmoil has disproportionately affected the Black community, and the record unemployment rate has hit the Black community hardest.

And then there is the constant threat that the police will kill you. That’s what finally ended Floyd’s life.

“It was not the coronavirus pandemic that killed George Floyd,” Ben Crump, the attorney for Floyd’s family, said at Floyd’s memorial on Thursday. “I want to make it clear, on the record. It was that other pandemic that we’re far too familiar with in America ― the pandemic of racism and discrimination ― that killed George Floyd.”

Ultimately, this boils down to a government response that treats Black people as if we are disposable.

Scott Roberts, senior director of criminal justice campaigns at Color Of Change

The coronavirus outbreak has hit communities of color hardest across the U.S. In Minnesota, where Floyd lived, Black people make up around 5% of the population, but accounted for 22% of total coronavirus cases in the state, the Minnesota Health Department reported. In the last few months, Black people in the U.S. have contracted COVID-19 at a disproportionate rate for a variety of reasons, like the lack of access to affordable and equitable health care, that experts say are often due to systemic racism.

Minneapolis police are seven times more likely to use force against Black people than against white people, according to data collected by the city. And while Black people account for only 20% of the Minneapolis population, around 60% of the time that police use force, it’s against a Black person.

It’s no surprise that these instances of systemic racism have built up to the current explosive moment. “What we’re seeing is a response to years and years of racial hatred,” said Scott Roberts, senior director of criminal justice campaigns at Color Of Change. “The Black community has simply had enough.”

Through all of this, the common thread is that the government refuses “to make the changes needed to protect and affirm Black lives,” Roberts said. “Ultimately, this boils down to a government response that treats Black people as if we are disposable.”

Dr. Tamara Lee, an associate professor at Rutgers University and a member of the Justice League NYC, told HuffPost the only way to fix this layered onslaught of threats to the Black community is to look at the history of racism in the U.S. and address it head-on.

“We have to have a serious conversation, as activists, as legislators, as a judicial system,” she said, “about how we repair 400 years of what this country has done that’s put Black people in the position they’re in right now.”

Calling all HuffPost superfans!

Sign up for membership to become a founding member and help shape HuffPost’s next chapter

[ad_2]

Source link