[ad_1]

It’s a small analysis, but helps paint a picture of how a few cases can turn into a pandemic — and how quick action can stop the spread, said Dr. Charles Chiu, a professor of laboratory medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, who led the study team.

“Probably one passenger brought it on board,” Chiu told CNN.

The strain that infected the passengers and crew on two voyages of the liner was the same strain that circulated widely in Washington state and elsewhere, Chiu added.

In contrast, another outbreak stopped with three people. One patient in Solano County infected two health care workers who cared for her, and transmission stopped there.

“That was it. It was an outbreak of three individuals,” Chiu said. In that case, contact tracing and quick isolation of the new cases stopped any further spread, he said.

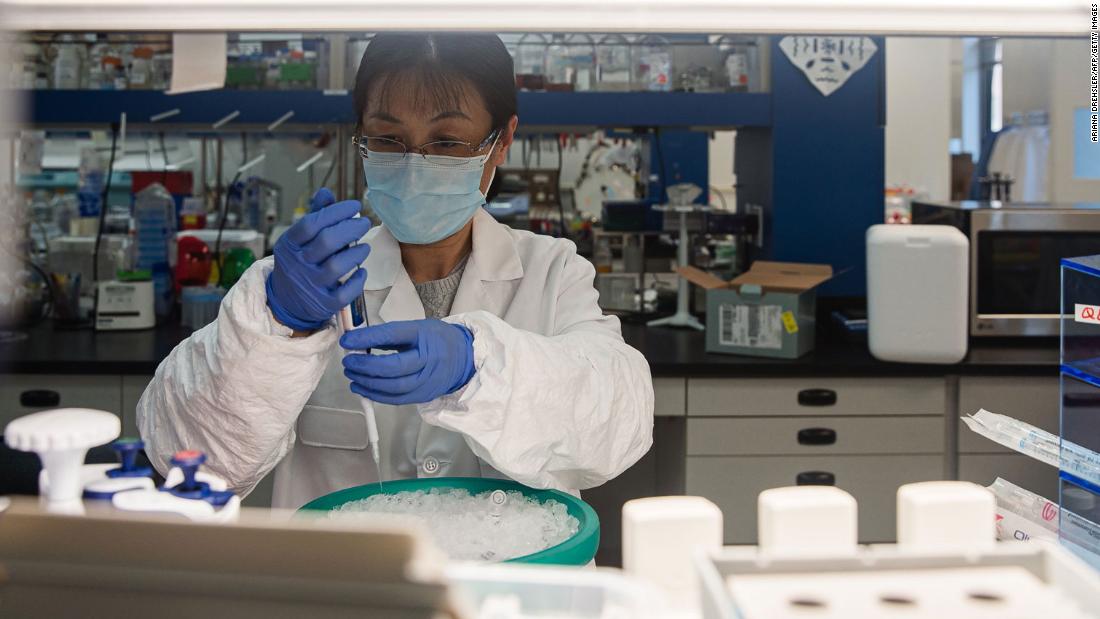

For the study, Chiu and colleagues examined viral samples taken from 36 patients in nine California counties. They sequenced the genomes directly from the samples using a new method called MSSPE (Metagenomic Sequencing with Spiked Primer Enrichment).

They were able to use this sequencing to identify each strain that infected each of the 36 patients, and compare them to other known sequences of circulating strains of the virus. Scientists are freely sharing this information so they can track the spread of the pandemic.

“We found out that there have been multiple introductions into California of different lineages of the virus,” Chiu said. At least in the first few weeks after coronavirus showed up in the US, it was not spreading freely across the state, but being introduced over and over in separate incidents.

“It shows that there were several different sparks landing in Northern California, many of which fizzled out probably due to a combination of public health measures and luck,” evolutionary biologist Michael Worobey, who was not involved in the study, told CNN.

Chiu said he hopes the gene sequencing method can eventually be adapted to do quick genome sequences directly from patients when they are first tested, to help public health officials track the spread of the virus and its origin.

The findings, he said, show many missed opportunities to stop the virus when it was seeded multiple times into California.

“We simply did not have the infrastructure to do the detecting that would have been needed,” Chiu said.

The findings also show that travel restrictions can work if they are started early enough and observed carefully.

“Social distancing interventions, such as the ‘shelter-in-place’ directive that was issued by the governor of California on March 20, 2020, may assist in stemming spread from community to community,” the team wrote.

[ad_2]

Source link