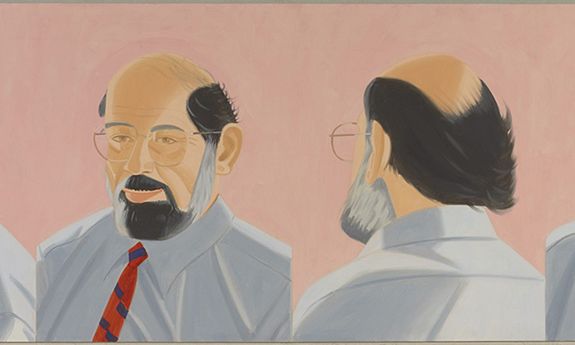

Alex Katz’s 1985 portrait of poet Allen Ginsburg will be on show at the Butler Institute

© Alex Katz/VAGA at ARS, NY, and DACS, London, 2024. Courtesy: Colby College Museum of Art

Among the many insights on our podcast A brush with… Alex Katz is how important poetry has been to the US painter’s art. Poets of the New York School like James Schuyler and Frank O’Hara, and others who followed, like Anne Waldman, “formed a natural audience for me”, Katz recalls. They also appear in his work: O’Hara among Katz’s first sculptural cut-outs; John Ashbery and his partner David Kermani at leisure in their Chelsea home; and Waldman, portrayed twice in a conjoined patterned headscarf in Face of a Poet (1972).

The poets’ world “was fantastic”, Katz says. O’Hara in particular “became my hero… he has an emotional extension that I really admired.” O’Hara’s 1960s text on Katz is among the most perceptive on him. “He has the stubbornness of the ‘great American tradition’ in the dominating face of European influences,” the poet wrote, articulating the central tension in Katz’s painting; Katz speaks of allying the “muscularity” of post-war US painters with the pictorial and emotional sophistication of Europeans including Cézanne and Bonnard.

O’Hara went on to describe “a ‘void’ of smoothly painted colour, as smoothly painted as the figure itself, where the fairly realistic figure existed (but did not rest) in a space which had no floor, no walls, no source of light, no viewpoint”. He added that Katz’s people “stayed in the picture as solutions of a formal problem, neither existential nor lost, neither deprived nor dismayed”.

It’s a reminder that art and poetry have long thrived in proximity. One thinks of Titian’s friendship with the poet Pietro Aretino, who was in effect the Venetian master’s propagandist. Aretino described how, in a now lost painting of Saint John the Baptist, the areas of flesh are “so well coloured that in their freshness they resemble snow streaked with vermillion and are moved by the pulsations and warmth of living spirits”.

Picasso was the definitive poets’ artist, preferring to surround himself in his “court” with bards more than fellow painters. Those who gained his favour (and often quickly lost it) included Guillaume Apollinaire, Paul Éluard and Jean Cocteau. Crucial to Picasso’s influence, as the late French poetry specialist LeRoy Breunig put it, was that the poets knew “not only the painting but the man”. Cocteau vividly described Picasso’s “struggle to get outside of himself” as a fight of religious intensity. “A real crucifixion results from the rages of Picasso against painting. Works made of nails, bandages, lacerations, wood, blood and bile.” Hence, Picasso’s impact was “felt by each succeeding group of poets in Paris” so that he was “a constant rallying point in the poetic revolution” of the 20th century.

Such alliances remain at the heart of artists’ work today: Alberta Whittle hails her “accomplices” for her own deeply lyrical work in sculpture and video installation, including many writers and poets. And Rachel Whiteread describes her interest in poetry’s economy—how “things are honed in on to such a degree that it’s just the sound of two words touching”.

That aspiration to the condition of poetry, whether it is for spare eloquence or the “emotional extension” Katz grasped in O’Hara, is at the heart of this symbiosis, among the most fecund through-lines in art history.

• Alex Katz: Collaborations with Poets, The Butler Institute of American Art, Youngstown, Ohio, US, 15 September-15 November

• Alex Katz: Claire, Grass and Water, Fondazione Giorgio Cini, Venice, until 29 September