Frederick Weston, New York Artist Known for Incisive Collages, Has Died at 74

Frederick Weston, the New York artist, performer, and fashion designer whose elaborate collages interrogated the media’s representation of New York’s Black and queer communities, died last week at age 74 from cancer. The news was confirmed by arts nonprofit Visual AIDS, of which Weston had been an active member of the group after his HIV-positive diagnosis.

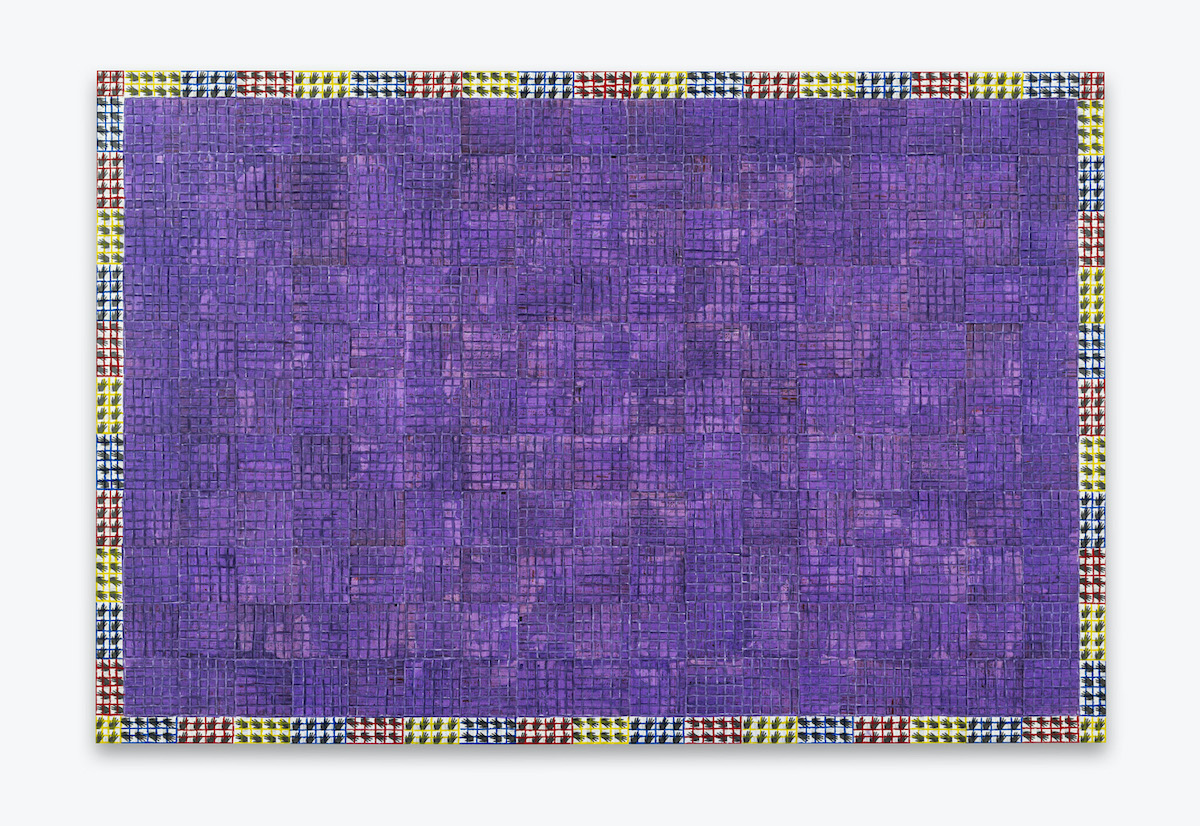

Weston was a dedicated archivist of mass media representations of men, amassing binders of magazine advertisements, paper ephemera, and fabric which he stored in his longtime Chelsea apartment and studio. (“Hoarding is about ownership and attachment. They really train us to be consumers,” he once said.) In addition to magazine clippings, his intricate and eye-catching collages were culled from photography prints, fabric swatches, food packaging—anything that could be duplicated with a Xerox machine.

“My whole practice really is about the way that men look, men comport themselves and the way that men pose,” Weston said in a 2020 interview with the Independent Art Fair. “What people wear are really where people’s heads are.”

Frederick Weston was born in Memphis, Tennessee, in 1946, and raised in Detroit by his grandparents and mother, Freda, who taught Weston to sew. After graduation, he spent a few years in Detroit working in the fashion industry alongside model Billie Blair, fashion designer Claude Payne, and jazz singer Stephanie Crawford.

In the early 1970s, the group moved to New York City, where Weston worked odd jobs while living in the Breslin (now the Ace Hotel Gallery). He and his fellow Detroit transplants were fixtures at Studio 54, the Loft, and other landmark venues in the Downtown scene, whose inhabitants would later populate Weston’s creations. In the ’80s, he enrolled in the newly formed menswear major at the Fashion Institute of Technology.

After graduating magna cum laude in 1985, Weston moved through various roles in the fashion industry, but pervasive racism embittered him to the field and he departed by the mid-’90s. The experience, coupled with childhood lessons in tailoring, proved formative in Weston’s lifelong artistic practice, as deconstruction of the male figure became a central preoccupation.

For his mid-90s series, “Blue Bathroom Blues,” the artist plastered a blue-toned collage of homoerotic imagery onto the walls of various construction site in downtown Manhattan. (Weston told an interviewer that one time a security guard, instead of arresting the artist, let him finish the piece.) His more recent collages took the shape of a series of roughly life-size paper figures plastered with a sundry of images that interrogate the intersections of Black culture and mass consumerism, as well as his own identity as a Black, queer, HIV-positive artist. In Body Map I (2015), the figure is overlaid with photos of Black public figures, most predominantly the face of Tom Morgan, a reporter and editor and the first openly gay president of the National Association of Black Journalists.

In 2019, Gordon Robichaux hosted the artist’s first solo exhibition “Happening,” which featured a selection of his work from the past two decades, including his forays into sculpture. In December, Ortuzar Projects will open an exhibition, organized in collaboration with Gordon Robichaux, that will present work from throughout his 40-year career, including new works made this year.

Earlier this year, Weston was named the third recipient of the Foundation for Contemporary Arts’ Roy Lichtenstein Award, which comes with $40,000 and goes to an artist “working and contributing to the creative arts in the wide-ranging and investigative spirit of Roy Lichtenstein,” according to the foundation’s website. At the time of his death, Visual Aids was finishing the seventh volume of its DUETS series, featuring Weston in conversation with author Samuel R. Delany.

Published at Tue, 27 Oct 2020 19:04:54 +0000