[ad_1]

Francesco Bonami, whose curatorial credits include the 2003 Venice Biennale and the 2010 Whitney Biennial, has returned for the sixth edition of his column, “Ask a Curator,” in which he addresses conducting studio visits virtually, reading recommendations for quarantine, and the film every curator should watch. He can be found on Instagram at @thebonamist. If you have queries for him for a future column, please write to [email protected]. —The Editors of ARTnews

You previously said that art fairs’ online viewing rooms cause the events to lose some of their magic. What are your feelings about museums’ online galleries? Do they offer the same experience as seeing art in a gallery?

The experience of an artwork online is never the same as the one you have in front of the artwork. But these times of isolation for all of us are a very healthy reminder that seeing art in person, whether in museums or in galleries, is a privilege of the few. The large majority of people in the world cannot afford to travel to cultural destinations or even afford museums’ entrance fees, so to offer an opportunity to enjoy art in a different way is extremely important. Art, after all, is one of the very few things we can enjoy remotely. It is not possible with food, or even with fashion. Art, like music, is something we can experience from our home, whatever and wherever that home may be.

The New York art world is largely shut down because of the coronavirus. How are you keeping yourself busy? Do you miss seeing art?

I don’t miss the physical experience. This tragedy has shifted my perspective. At night I have exclusively—though not necessarily scary—dreams about the pandemic. The other night I dreamt of the president of the MAXXI in Rome and Covid-19 was the subject of my conversation with her. That was scary.

Many dealers, critics, and curators are conducting studio visits right now by video call. Are you opposed to using FaceTime and Zoom to do studio visits?

I rarely do studio visits. I never liked them too much particularly when you don’t have a specific project in mind. But why should I be opposed to other people enjoying them even via FaceTime or Zoom? These mediums definitely diminish the pain of the experience and save a lot of time and taxi fares. But if I have to give a piece of advice: we should face the fact that things are subverted and certain things we have to give up for the time being. There are people who are doing cocktail hour online with friends. There are experiences you want and need to do for real in the same space with others and augmented reality has not yet reached this kind of perfection, thank God. To miss something, to long for someone is a healthy way of processing or mourning a loss, even if a temporary loss—and even if I feel that longing for studio visits is a little perverse.

What is one thing that you know now that you wish you knew when you started curating?

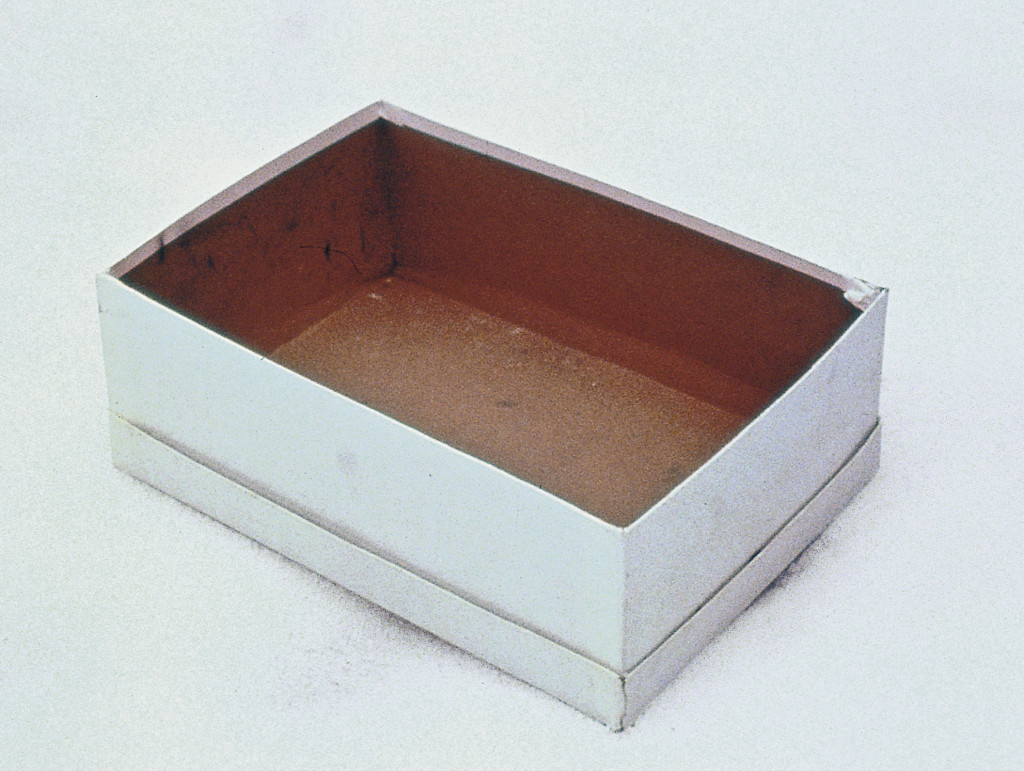

My whole career moved, progressed, and regressed because of me not knowing many things. Ignorance is not a quality but sometimes it can help you to be more spontaneous or daring, even brave, without knowing you were brave. So now I know more things than in 1992 when I started curating but this does not help me at all. I’ll give you an example of my ignorance: In 1993, when I curated a section called “Aperto” at the Venice Biennale, I invited Charles Ray. I was absolutely not aware he was already a very important artist. I truly did not know who he was. I liked the work but did not know much about it. When he brought to Venice his 7.5-ton white cube, we had serious issues of where to place it—where he demanded it be placed—because I did not know him and I was not intimidated by his fame I was able to send him to hell. We became great friends after. Today I would not dare to do such a thing. But one thing I wish I knew then is not to panic in front of a problem or a setback. It’s never the end of the world, and in case another world will start and that’s OK too.

With everyone stuck at home, some people are turning away from their screens to their bookshelves. What are some from yours that you would recommend as quarantine reads for art world folks?

I don’t read much, but I browse a lot of books. One I go back to often is The Geography of Thought by Richard Nisbett, which is about how Western and Eastern thought differ. Urs Fischer suggested me for this particular time of the coronavirus: Concrete Island by J. G. Ballard. And another friend told me to read Il’ja Il’f and Evgenij Petrov’s The Twelve Chairs, a very funny Russian novel from 1928. I also browse through Chantal Delsol’s Praise of Singularity—like we need that. But my favorite reading is Luciano De Crescenzo, a self-made philosopher from Naples and a popular figure in Italian culture. His History of Philosophy and Roughly, Praise of the Almost are great! Superficially, they have nothing to do with art—but deep down they do.

The dealer Paul Kasmin died last week and a couple of his artists have been very vocal about the supportive role he played in their lives. For a curator, what are the best qualities in an art dealer?

I never really knew Paul Kasmin, but I felt he was an old-school dealer, the right kind, not much bullshit, not so much in touch maybe but solid and consistent. For me the best qualities in a dealer are charisma, a dose of shyness unless it becomes dangerously obnoxious like in Matthew Marks, and a sense of scale, which doesn’t mean big or small but being able to express one’s own space in the world. Sonnabend and Castelli represented most of these qualities and for charisma young dealers should study Colin de Land. He was the master of it, verging into psychopathy. He was great! Dealers should not try to be Jeff Bezos or Mark Zuckerberg. Not even Barack Obama.

Art Basel has been postponed to September. Are you a regular attendee of the annual fair? How might it be different in September, assuming everything goes according to plan and we don’t have lengthier coronavirus disruptions?

I really enjoy Basel as a city, so I went there with pleasure. June was kind of the end of the school year. Afterward, you could withdraw and not think about the art world for a while. So in September, it will feel more like the beginning of school year, which I hated terribly—but maybe not. After this intense winter and spring, people, and in particular collectors, will have been able to get the monkey of the crisis off their back, and they will crave to start buying again, hopefully with more autonomy and enthusiasm than before, following their eyes rather than those of—no matter how smart they might be—art advisors, who should turn into something more like agents for collectors, dealers and artists. The rules when—if—we exit this tunnel will change. There will be more flexibility. We will all scale down but in a good way most of the time. Some will stay in the tunnel, but that’s the tragedy of any war. Speaking again about scale, art is about people, usually two—the artist and the viewer. Unless we are talking about Gilbert and George or Fischli and Weiss—then it’s about three people.

Here at ARTnews, during this crisis, we’ve been thinking a lot about art that has come out of difficult times, and particularly art made during pandemics. What are some examples you look to?

Well, I don’t have examples for a pandemic, but a crisis, yes. Two examples. The 1992 show of Matthew Barney at Barbara Gladstone on Greene Street in Soho was a revolution that would not have been possible in the ’80s bonanza of the market. The crisis allowed the gallery to take chances, since the sales of hot artists were dead. Few could have predicted that Barney would have turned into the hottest artist of his decade. The other example is the “Oktober 1977” cycle of painting by Gerhard Richter done in 1988, the black pit of the economic crisis. Richter was famous but kind of dismissed by the trendy artists of the ’80s. The Baader-Meinhof series of paintings placed him on a pedestal of some kind of political or conceptual painting he could care less about, but yet it propelled his work and his market.

A crisis gives people time to improve the way they look at art. Fear kills fear. Fear to do the wrong move or the wrong choice or to piss off someone in the art Power List. Crisis kills what I call the “rampant cowards,” those people who die to be at the top but are terrified to do anything wrong, to take chances or risks of any kind. The method of the Survey Generation—those who, before saying something, check how many people will agree on what they say, like some kind Gallup strategy, what will not work once all this mess is gone. You need to take some risks and make lots of mistakes if you want to make things work again.

Young curators are always searching for inspiration. Is there any work—be it a book, film, album, or anything else—that all young curators should experience?

I am watching a very long but fantastic movie—Andrei Rubliev by Andrei Tarkovsky—that has a lot to say about art. The monk Andrei Rubliev stops talking and painting because of the utter violence he witnesses around him but then he meets this young guy who claims to be his father, a bell maker, and before dying tells him the secret of how to cast a bell. A Prince asks a boy to cast a bell and the boy, who appears cocksure, in fact knows nothing. He proceeds, guessing, but at the end the bell works and the boy starts crying and in front of this kind of irresponsible faith Rubliev starts talking and painting again. What we need is irresponsible faith—risking our heads. Another thing a curator should look at is Seinfield, the famous TV series about nothing. The opening exhibition in spring 2021 at the new Tian Mu Li/JNBY art center I am involved with in Huangzhou, China, will be titled “A Show About Nothing.” We hope it will be as fun as as a Seinfield episode.

[ad_2]

Source link