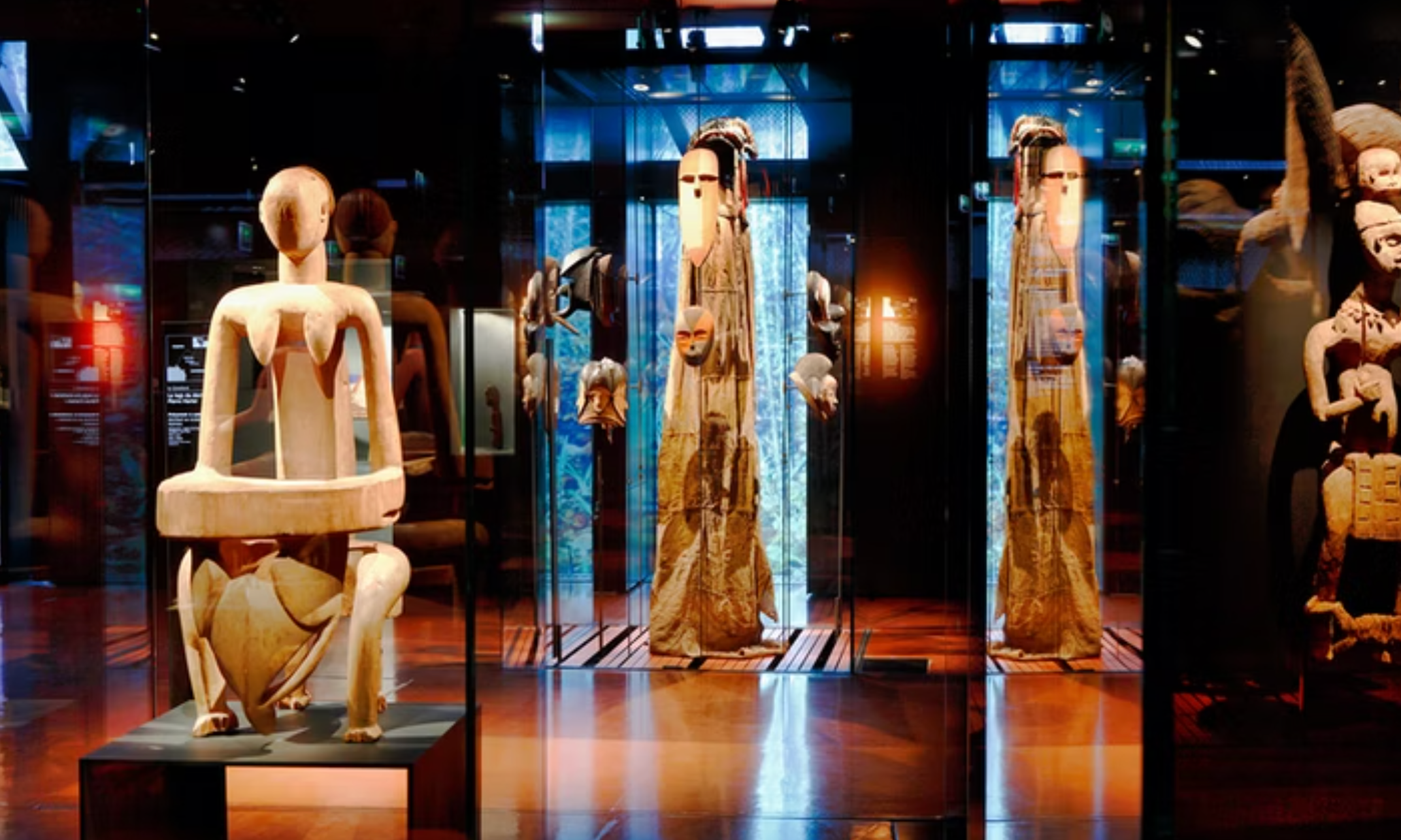

The Quai Branly museum in Paris has around 300 objects in its collection that could be flagged by a new report commissioned by the French state on restitution

© Musée du quai Branly

France is finally releasing its long-awaited policy on the charged issue of the restitution of cultural property. The government will tomorrow make public an 85-page report on the subject by Jean-Luc Martinez, a former director of the Louvre. The report was commissioned by President Emmanuel Macron and the government has already implemented some of its recommendations, most notably a bill on art looted by the Nazis, which will be discussed by the Senate on 23 May.

And a further two laws will be passed in coming months, according to the culture minister Rima Abdul-Malak. One could apply to items from the former colonies of Western empires, which the report defines in global terms, rather than just Africa and its former French dominions. The other pertains to human remains.

Martinez tells the Art Newspaper that his report recommends studying the requests for restitutions by eight African countries to establish a “criteria of returnability”. Rather than basing this on an ideological or moral standpoint, he says he wishes to take a "pragmatic approach in order to define a framework policy of restitutions".

He has come up with two main criteria as the basis for restitutions: "illegality and illegitimacy". For example, according to French law at the time of France's colonial invasion of Algeria in the early 19th century, weapons can be legally seized from an enemy but cultural goods had to be returned after battle. So the books and clothes of the rebel leader Abdelkader ibn Muhieddine (commonly known as Abdelkader) should have been given back to him when he surrendered, making their status in France "illegitimate".

Likewise, if an officer handed looted goods to a French museum, as was the case for many objects looted from the Kingdom of Benin, the donation should be considered "illegal because such personal war booty is not allowed." A key recommendation of the report is that requests for restitution be studied by a bilateral scientific commission which will publicly provide an opinion before the final decision of French courts.

Martinez says that despite the apprehensions of curators, very few works held by French museums will fall under these definitions. "Out of the 85,000 objects examined by the Quai Branly museum in Paris, only 300 are problematic and could correspond to these criteria". His report also emphasises that requests for restitutions should come from the state, which must, in turn, ensure that the works be well kept and exhibited after their return.

The report also suggests making restitutions to foreign nations easier, once the criteria for their return have been fulfilled. Currently, restitutions of any kind must be approved by special laws, which can take years. The law already introduced on artworks looted by the Nazis, according to Martinez’s report, will also facilitate their deaccessioning and extends the definition of looted art beyond the time and space of German occupation of France, and into the 1933-1945 period across Europe.

This report comes nearly six years after Macron publicly called for the “return of African heritage” during a state visit to Burkina Faso. And it has been four-and-a-half years since the academics Bénédicte Savoy and Felwine Sarr made the case for systematic restitutions to African countries. Since then, the issue has been somewhat downplayed, but it remains a sensitive subject.

Some Paris museums, like the Quai Branly, the Museum of Mankind and the Army Museum, have in recent years discreetly created new departments for researching the provenance of their collections during the French colonial period, with contributions of African scholars and curators. Martinez closely followed these initiatives and also reviewed the position of other European nations as well as consulting with concerned African states. His report provides the first synthesis of restitution policies throughout Europe. He underscores the specificity of French public collections, which are considered forever inalienable.

“They do not belong to the state, they belong to the nation, and the state is only their keeper” he says. “It’s the big difference between France and other Western countries. where each museum can decide such matters on its own." Martinez concludes his report by proposing that European and African countries establish a common framework for restitutions, like the 1998 Washington principles on looted art, and establish a fund to help such new cooperation.