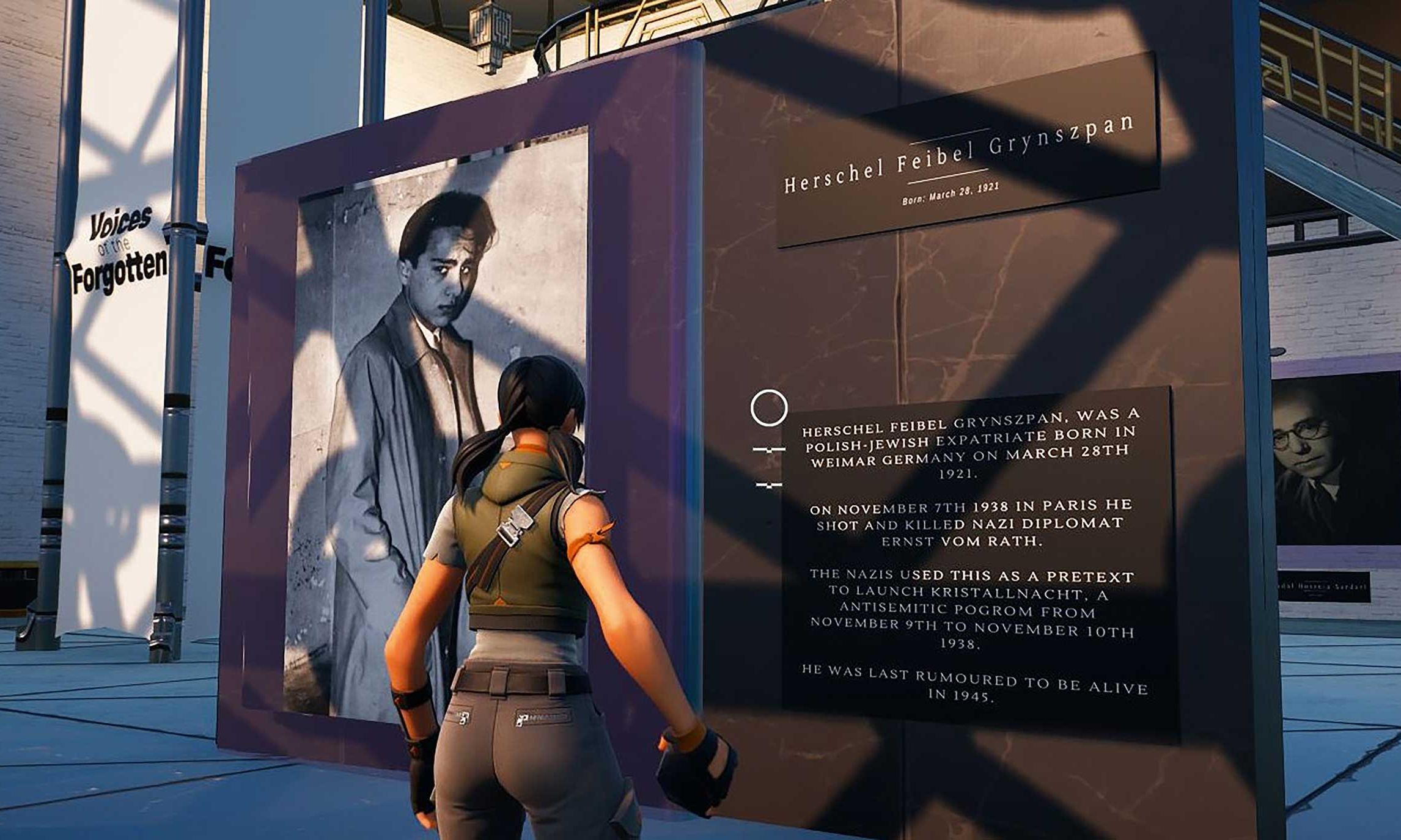

A player in Fortnite explores Holocaust exhibitions at Voices of the Forgotten, a virtual museum created by Los Angeles-based game designer Luc Bernard

Courtesy Luc Bernard

Millions of players of the online video game Fortnite can now visit a virtual museum dedicated to the Holocaust.

Amid Fortnite’s battle royales and combat arenas now stands Voices of the Forgotten, a virtual museum launched in August of this year. It was created by the Los Angeles-based game designer Luc Bernard, with approval from Fortnite’s publisher Epic Games. The museum lets players navigate through exhibitions on the Holocaust, with galleries telling stories of historical individuals like Abdol Hossein Sardari, an Iranian diplomat who helped Jewish people escape occupied France, and Haika Grosman, who was involved in the Jewish resistance in occupied Poland. It also contains displays of lesser-known antisemitic attacks from this era, like the 1945 anti-Jewish riots in Tripolitania, which killed or injured hundreds of people in North Africa.

“Video games are the most used platform in the world, so it made no sense that we hadn’t been able to address this history there,” Bernard tells The Art Newspaper. (He previously created The Light in the Darkness, a free game that follows a Polish Jewish family in Nazi-occupied France.) Bernard says his inspiration for a Holocaust museum in a video game came from both the inherent storytelling qualities of the medium and a significant concern about resurgent neo-Nazism in the United States. He adds that, for him, the need to push back against recent increases in hate and antisemitism is “a matter of life and death”.

Bernard himself came under attack when his museum project was first made public. The launch of Voices of the Forgotten was delayed after he faced online harassment from white supremacists and Holocaust deniers. Bernard says that “emotes” (dances or other actions players can perform) and vocal chat have been disabled in the space, and although a handful of players have tried to block the view of exhibitions by standing in front of them, the response has been overwhelmingly positive.

“It’s exciting to see where this all goes, but it doesn’t replace real museums,” he says. “It just allows anyone in the world to access one, and it gives them equal awareness.”

Bernard’s virtual museum comes at a time when antisemitism has been on the rise in the US. This month marks the fifth anniversary of the Pittsburgh synagogue shooting, the deadliest antisemitic attack in US history. In September, in the lead-up to Rosh Hashanah, as enhanced security was brought to synagogues across the country, President Joe Biden said that hate and antisemitism had been given “too much oxygen” in recent years.

Fortnite has been highly popular since its 2017 release, still ranking at the top in September for free-to-play games downloaded to PlayStation 4

and 5. But on the Anti-Defamation League’s 2023 Online Holocaust Denial Report Card, the game received a failing grade, noting that multiple players reference Holocaust denial in their usernames and stating, more generally, that “Holocaust deniers have used social media and game platforms to spread their virulent ideas and garner support”.

A museum about the Holocaust’s atrocities in a video game better known for its pop-culture “skins” (which allow players to appear like characters from TV, movies and other games) and massive competitive fights may seem like a questionable fit, particularly when taking into account the ongoing debates about how best to recount the history of the Holocaust in public spaces. But as strange as it may seem for avatars of, say, Spider-Man or John Wick to stand quietly in front of museum displays while their players read about the Holocaust, the experience is intended to make history accessible to young people online, where that history is regularly denied and distorted.

The creation of museums within video games, designed to do something a physical museum cannot, has received increasing attention in the wake of the pandemic. But museums have long had a presence in video games as a form of worldbuilding. From the Rapture Memorial Museum’s displays of propaganda behind a fallen utopia in BioShock 2 (2010) to the Museum of Dwellings, a narrative space that reinforces themes of searching for home in Kentucky Route Zero (2020), video games have been designed with museums built into them, which play an important part in their storytelling.

“The ways that games implement museums show us how people in game development view museums, artefacts and collections,” says Kaitlyn Kingsland, the editor of Archaeogaming—a blog about the archaeology of and in video games—and a research associate at the University of South Florida’s Institute for Digital Exploration.

James Newman, a research professor in media at the UK’s Bath Spa University and the senior curator at The National Videogame Museum in Sheffield, notes that in the game Animal Crossing: New Horizons (2020), the player is tasked with discovering and then either donating or selling the potential exhibitions. “This always struck me as interesting: placing a public cultural institution at the heart of the game’s virtual world,” he says, adding that the player is “frequently confronted with the decision to build their personal wealth versus donating to and enriching the museum for the public good”.

“Using video games that have an established audience base creates the opportunity to connect with people who may not visit museums on their own terms,” says Alec Ward, the digital skills manager at Culture24, a UK-based non-profit that supports cultural sectors online. “The challenge is that the experiences you create need to be something those audiences actually want to play, which is always the hardest part.”

Some bricks-and-mortar museums have been directly involved in the development of video games. The Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, for example, was part of the development team behind Discover Babylon (2006), an educational game about ancient Mesopotamia that was intended as a model for other museums for how to use digital experiences in their outreach.

“When I think about what museums can learn from video games and what the reciprocal relationship can be, it’s how video games direct people’s attention, how they encourage interaction and storytelling,” says Marie Foulston, an independent curator and creative director who specialises in video games. “That can be carried across into physical exhibitions, but also into what our ideas or expectations might be for digital or virtual exhibitions.”

Among the projects Foulston cites as succeeding at merging what gaming and museums can offer is Pippin Barr’s v r 3 (2017), a virtual museum that presents renderings of water on plinths to consider the challenges of replicating a liquid that is so ubiquitous in the real world. There is also the Pittsburgh-based LIKELIKE, a new-media art gallery and arcade that, in 2020, introduced “the tiniest MMORPG” (multiplayer online role-playing game), where visitors can interact while experiencing rotating exhibitions.

There are limitless possibilities in connecting art, heritage and history to audiences for whom virtual spaces are their primary cultural platform. And, as demonstrated by the Holocaust museum in Fortnite, there are resonant ways to address complex topics that have long been presented by museums but not as frequently in games. But perhaps most importantly, the experiences of exploration and discovery in games can provide new ideas of what a 21st-century museum experience can be.