[ad_1]

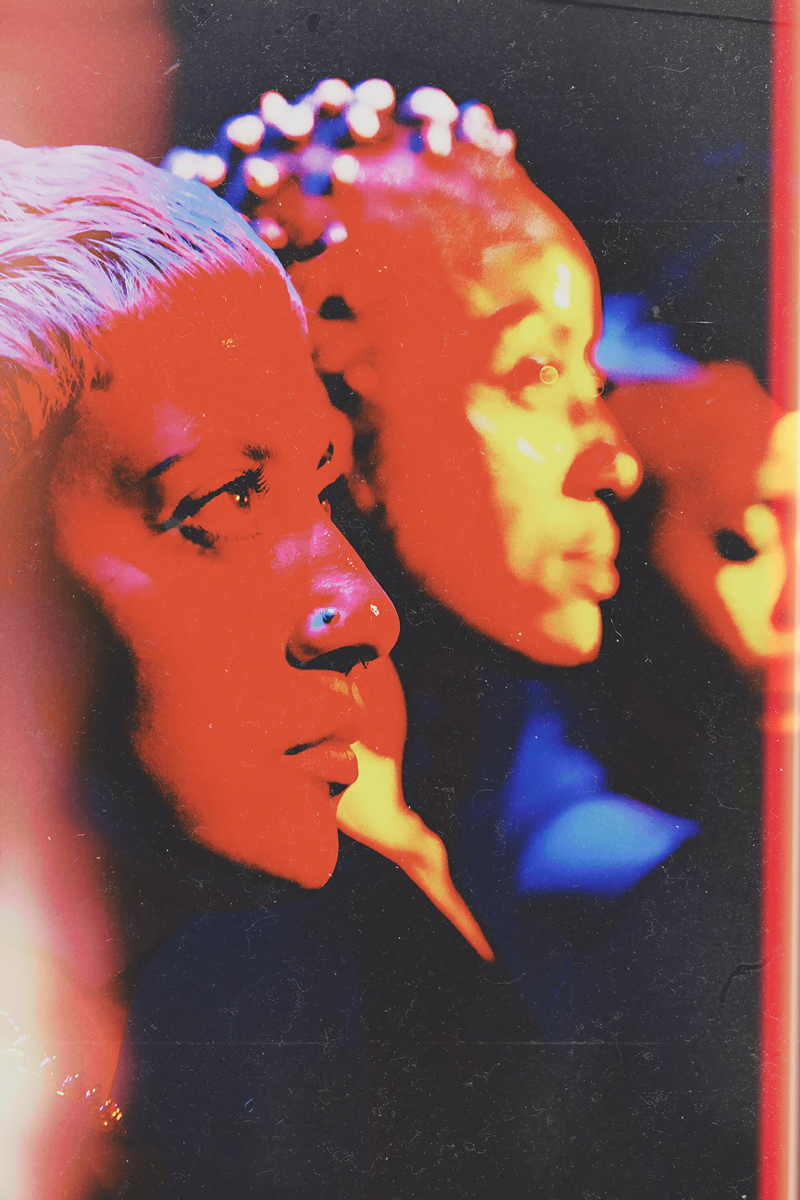

Kia LaBeija’s latest self-portrait work Untitled, Residency Blue, 2019.

COURTESY THE ARTIST

On a recent morning in a nearly vacant rehearsal room at the arts center Performance Space New York, two dancers were staring at each other and mirroring other’s movements. One would slowly raise an arm with a shark fin–like form attached to it, and the other would follow suit. All the while, they maintained eye contact.

Kia LaBeija, the artist overseeing the dancers, watched as the dancers performed. She wasn’t totally satisfied—they weren’t moving in sync. She brought the rehearsal to a halt, and said, “This is a fight—you have to fight for it.”

She came over to the dancers and, like an admonishing but loving parent, firmly told them what they needed to fix. “It’s about attitude,” she said and immediately composed her face into a fierce pose, with a piercing gaze. “Just as you sell face on that ballroom floor, please sell face to your sister.”

“They’re fighting for themselves,” the artist told me a few days later.

LaBeija, 29, is best known for her autobiographical work in photography, producing a body of images that focus on her life as a young queer woman of color born HIV-positive to an untested mother that also holds space for those with similar experiences.

She sees this duet—the central and most demanding section in her newest work, Untitled (The Black Act), a commission for the performance art biennial Performa, that debuts today—as a visualization of confronting of one’s ego. “You have to fight to stay in that place when you confront yourself because that’s one of the hardest things we can do as human beings. I want these girls to fight to stay to be able confront themselves in confronting each other.”

Kia LaBeija’s Untitled, The Dueling Duet, 2019, is a preparatory photograph for her newest work, Untitled (The Black Act), a co-commission by Performa and Performance Space New York.

COURTESY THE ARTIST

For the eighth edition of Performa, the curatorial team, led by its founder, RoseLee Goldberg, has looked toward a historical anchor—Bauhaus, the storied German art school that blurred the lines between artistic forms in the first half of the 20th century—and LaBeija has approached it with both careful study and irreverence, bringing her involvement in New York’s ballroom culture and, more generally, contemporary queer life to bear on the 100-year-old movement.

LaBeija has taken as inspiration one of the most famous pieces to come out of the Bauhaus, Oskar Schlemmer’s Triadic Ballet, a surrealistic composition in which dancers move, almost mechanically, in meticulously sculpted, machine-like costumes to music by Paul Hindemith. In the trailblazing piece, Schlemmer was interested in how modernity had already begun to alter people’s everyday lives, down to their basic movements.

LaBeija brings that investigation into 2019, examining how digital photography, and Instagram in particular, has altered the way people form their own self-image. She has tapped Kyle Luu, whom had previously styled her, to create the costumes, elegant and equally sculptural forms that accentuate the female body through hip pads and more.

First staged in Stuttgart in 1922, the Triadic Ballet is divided into three parts, based on the color schemes of the lighting. First is yellow, then pink, and then, finally, the “Black Act,” in which, illuminated by spotlights, the dancers move across a black set with floor-markings of a spiral, a line, and a grid. Little documentation of the original performance exists, but LaBeija has drawn liberally on what is known of Schlemmer’s ballet and its style, however she’s made a crucial alteration—her dancers are all women of color.

“Schlemmer abstracted these bodies,” LaBeija said. “In a way, that’s what we’re doing now. We’re getting so much work done to mimic the bodies of women of color—bodies that used to be shamed.”

Kia LaBeija’s Untitled, The Spiral, 2019, is a preparatory photograph for her newest work, Untitled (The Black Act), a co-commission by Performa and Performance Space New York.

COURTESY THE ARTIST

She views Bauhaus as having been “intersectional” in the way it blended so many different art forms, from filmmaking to design. Her approach is intersectional in different ways. In addition to her casting, she’s combined music, which draws on meditation practices and healing modalities (by her brother, Kenn Michael, who is accompanied on percussion by their father, Warren Benbow) and movement (by her partner, Taína Larot). And four black artists—Mickalene Thomas, Racquel Chevremont, Jet Toomer, and Nina Chanel Abney, working under the collective moniker the Josie Club—have signed as co-producers.

Untitled (The Black Act) has no formal choreography or specified actions—a fact that make’s the dancer’s mirroring all the more impressive. LaBeija, who was trained in ballet and modern dance, prefers to think of it as a “movement” piece instead of a dance work. But there are references to the dance style of the House of LaBeija, a hallowed New York ballroom house that the artist joined when she was 19. It’ll never look the same way twice.

“I had so much structure that I didn’t know who I was outside of someone telling me how to move,” LaBeija told me. “When voguing found me, I felt for the first time this freedom. I didn’t have to dance to someone else’s story. I could just be myself. I wanted to experiment by giving that freedom to other folks.”

“The ballroom scene is its own Bauhaus,” Job Piston, special projects manager at Performa, which co-commissioned the piece with Performance Space, said. “It’s about a dance floor where people come together. It’s its own school of learning movement, visual arts, music, social history, pleasure all within found, reclaimed, and fantasy architecture.”

Kia LaBeija’s Untitled, The Grid, 2019, is a preparatory photograph for her newest work, Untitled (The Black Act), a co-commission by Performa and Performance Space New York.

COURTESY THE ARTIST

Each section of Untitled (The Black Act) has special resonance to LaBeija’s own life, in particular the third part, which is set on a 7-by-7 floor grid, with each square about one square foot. After one early meeting with the Performa team, she realized she wanted to work with the grid of New York City, where she was born and raised. “I was thinking about how Manhattan was this island that was completely demolished and erased, and this grid was built for ‘beauty, convenience, and order,’” she said, quoting from the Commissioners’ Plan of 1811 that created Manhattan’s grid, north of 14th Street. “Every day you walk this path that has already been forged for you. New York is just that crazy kind of place where anything is possible.”

From there, LaBeija decided she wanted to create a piece about the process of healing, with each section being part of one’s journey toward that healing. “It begins with something that happens in our lives and we spiral out,” she said of the first section. “Once you realize that the spiral is a positive thing, a healing crisis more than anything else, you can go into the next phase of addressing the issue, addressing yourself really.”

In the next part, the duet, two dancers oscillate between mirroring each other, following each other’s lead, and connecting their bodies. LaBeija sees it as a metaphor for the ways in which “you have to confront your ego and the way you have to be able to look at yourself” before making it to the grid, which is a phase for figuring out what comes next.

During the grid section, the three dancers start on one end of the 7-by-7 grid and, as LaBeija put it, “take a walk.” One dancer walks down the center and along the edges primarily en pointe, while the other two walk about the interior. When they meet, they put their bodies together to form a sculpture. At various points throughout a voice (LaBeija’s) speaks over the music in the digital stilt of a GPS announcer that says “rerouting” or “recalculating,” a cue that tells the dancers to collapse.

In preparation for the duet section of the piece, LaBeija had the two performers, Daniella Agosto and Selena Ettienne, whom LaBeija considers her daughters, stare into each other’s eyes for intervals of 5 minutes and 10 minutes as they must maintain eye contact with each other for the entirety of the duet. “If you keep your eyes together, you’ll automatically know what the other is doing because you can feel it,” LaBeija said. “It’s not an easy thing to, but if you can, you’ll see things you could never see before.

“It was a hard process because I’m an over-thinker,” Agosto said. “In dance, we all want to be the best we can be, so we beat ourselves up about it a lot to be the best. With doing this, you can’t think about anything else. There’s no thinking. It’s whatever comes to you.”

Another one of the dancers, Khristina Cayetano, said, “Through this process over the past couple of months, I’ve learned to trust myself more as an artist. This piece helped me get back to the truth, the idea that art is life and that they’re not separate.”

Though the finale of the performance represents a release, LaBeija sees this healing as a never-ending process that manifests in continuing cycles, one that requires making peace with all the parts of oneself.

“We live in a world where everyone is always masked,” LaBeija said. “I remember my mom told be that when I was a kid. I didn’t understand what she meant then. The question is always, ‘Who are we?’ I don’t know if that’s something that we ever figure out.”

[ad_2]

Source link