[ad_1]

Nicole Eisenman, Egg-Eater, 2018, at One Night Only in Dallas.

KEVIN TODORA/ANTON KERN GALLERY

It is tough being a Nicole Eisenman fan these days. That’s not because of any change or decline in her work—quite to the contrary, it’s as venturesome, surprising, and charming as ever—but rather because her recent exhibitions have been achingly brief affairs. To see them, one has had to be in the right place at the right time.

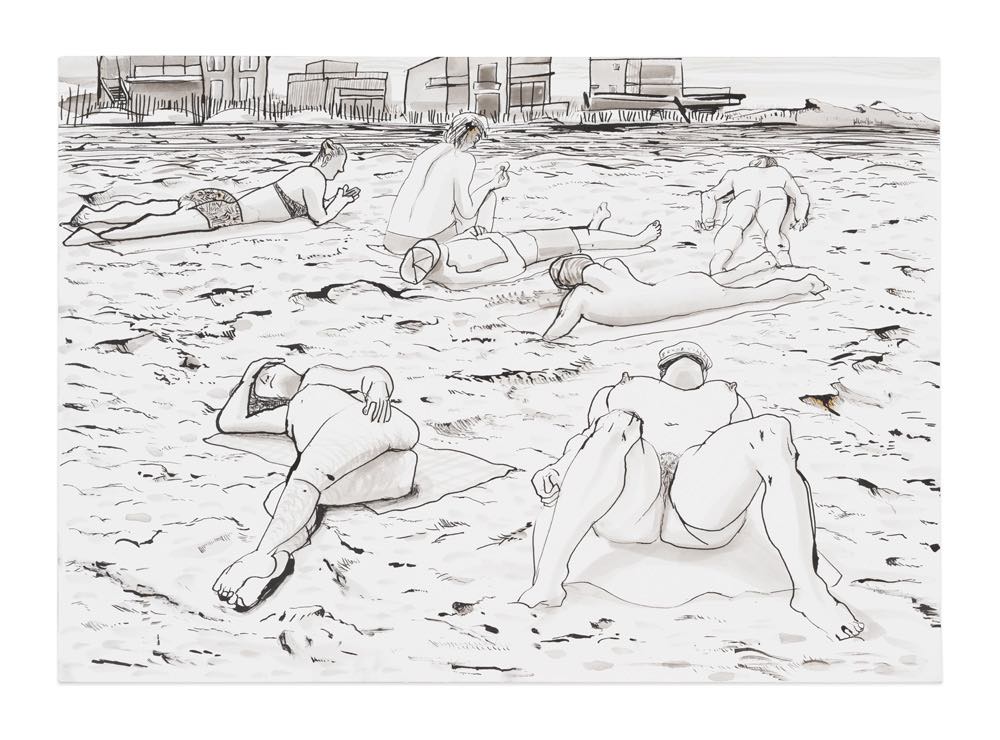

Two months back, at Anton Kern Gallery in New York, Eisenman offered up a ten-day exhibition tied to Valentine’s Day that had a suite of some two dozen drawings and paintings. It was a generously intimate affair, filled with scenes done in a panoply of styles of friends lounging on Fire Island beaches. They are sleeping, reading, drawing, drinking Modelo Especial; many are naked, thoroughly at ease. I found my heart-rate slowing as I looked at them.

Nicole Eisenman, People on the Beach, 2017, included in “A Valentine’s Day Show” at Kern in February.

COURTESY THE ARTIST AND ANTON KERN GALLERY

In the loose and virtuosic pencil-and-ink piece People on the Beach (2017), there are seven people, each off in their own world, soaking in rays or punching away at a cell phone on a beach, its sandy ridges fashioned from a compendium of various quick marks. The largest figure is on her back with her feet on the ground and her knees in the air, spread apart; a hat covers her face. We are there, but she is somewhere else, dreaming.

This past Friday evening in Dallas, a remarkably similar figure could be found in a four-hour show that Eisenman staged at the appropriately named One Night Only, a space run out of a humble, ramshackle two-room house in the quiet Cedars neighborhood by artist Arthur Peña as part of his practice. But here, the female figure in question was hiding, and I will admit that I had to schedule a return visit to see her, after being tipped off to her presence. (Appointments were available after the opening.)

Detail view of Nicole Eisenman’s Hook ’em Horns (2018) at One Night Only.

ARTNEWS

Peering through a small hole in a door in the house, one could make out a reclining figure, again with two raised knees, but in this piece—cut from a thin slab of wood usually used to make prints—there is one key difference: her right hand has found its way between her legs, and she is feeling herself with two fingers, so that her hand resembles the sign of the horns, or the Hook ’em Horns that University of Texas fans flash at sports games.

Even knowing what I was about to witness, it was shocking to behold, like suddenly discovering that the dead-looking woman in Duchamp’s Étant donnés (1946–66) had sprung to life, as though she’d decided that she’d had enough of being ogled, and was instead going to enjoy herself, voyeurs be damned.

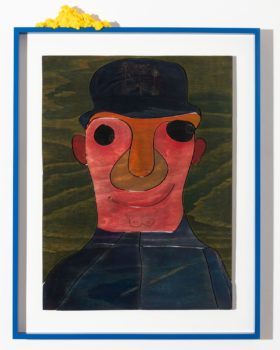

A few printing woodblocks were on the walls of the front room—curvy, elegant portraits that Eisenman had previously inked to make prints. She has has dubbed them “WudCutz™,” and some of their prints are no doubt out in the world now, being viewed by who knows how many people, but here were the sources for Eisenman’s endearing characters, staring or smiling at all comers. Vaguely recognizing one, of a big-lipped figure kissing a bird, I had the peculiar joy one has when spotting a great character actor walking along the street while not quite being able to name their most famous roles.

Nicole Eisenman, Josh, 2018.

KEVIN TODORA/ANTON KERN GALLERY

Subtle details are incised onto the surfaces of the WudCutz™. In one, a jolly individual with skin the color of grapefruit flesh has a cap with the New York Yankees logo scratched on it and a tiny chin that almost looks like breasts, testicles, or maybe some combination of the two. How much of these minute marks, one wonders, makes it into the prints? Or, to stretch that question, what gets elided or obscured when images—to say nothing of ideas—are circulated, shared, or reproduced?

In the back room of the house there was a little sculpture of angular, gray aluminum planes—an abstracted figure crouching atop a pedestal and chomping at what seems to be a slice of bread. The work is called Egg-Eater (2018), and a mound of brilliant yellow paper pulp sits atop the toast, looking like perfect scrambled eggs. Which, come to think of it, could be a nice metaphor for Eisenman’s practice: unafraid to crack open new ideas, toss them in the pan, and apply heat, making apparently effortless delights with great care. (Good scrambles are no easy thing.)

The pulp’s also on the Egg-Eater’s head and back, and atop the frames of some of the WudCutz™. It’s on the floor, the walls, and even outside the house, on a fence and a tree. It seemed to be growing larger, spreading wider. Pretty soon, you sensed, the Egg-Eater was going to go chasing after it, devouring it up with all the energy that is the hallmark of Eisenman’s practice. For that one Friday night, though, it was busy with its slice of bread, and so we had a little bit of time to take it all in.

[ad_2]

Source link