[ad_1]

Installation view of “Harmony Hammond: Material Witness: Five Decades of Art,” 2019, showing six examples from her “Presence” series, 1971–1972, at the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, Ridgefield, Connecticut.

JASON MANDELLA/©2018 HARMONY HAMMOND, LICENSED BY VAGA AT ARTISTS RIGHTS SOCIETY (ARS), NY/COURTESY THE ARTIST AND ALEXANDER GRAY ASSOCIATES, NEW YORK

Six fabric sculptures appearing slightly larger than life size hang from the ceiling and graze the floor, inviting viewers to join them. Paint applied by artist Harmony Hammond imparts earthy tones to these layered scraps of cloth. Spots of bright color and pattern peek out here and there—plaids, polka dots, florals.

Hammond created these works in the early 1970s when as a young artist she was active in the burgeoning feminist and gay and lesbian rights movements. She calls them “Presences” because, as she said, “they speak to the history and power of creative women, as well as feminist collectivity. They are about occupying space.”

They evoke a community of wild women: elders, mothers, crones, outlaws even.

These weighted ceremonial garments feel at once ghostly and corporeal. Hammond constructed them from scraps of cloth ripped from worn-out clothing, curtains, and bed linens donated by friends—fellow lesbians, feminists, artists. She dipped the fabric in thinned acrylic paint to saturate it, weathering and toughening its surface, then tied and stitched the pieces together. Walking among the pendant sculptures, I think of prior generations of lesbian, feminist, trans, and gender-nonconforming artists, paving the way to the future.

Harmony Hammond, 2019.

CLAYTON PORTER

“Lesbian erasure is not acceptable,” Hammond told me recently. “We have no choice but to be vigilant.”

Hammond speaks with the conviction of someone who has been fighting for visibility in the art world—and beyond—for a very long time. She is now seeing that activist labor bear fruit on an ever-widening scale, with a survey of her career at the Aldrich Museum of Contemporary Art in Ridgefield, Connecticut, pieces in four queer-themed shows across the country this year, and a solo show of recent work at White Cube in London this fall.

“Hammond’s practice has always shown a profound commitment to bending boundaries and showing their radical energy,” said Amy Smith-Stewart, curator of the Aldrich show, entitled “Material Witness, Five Decades of Art,” on view through September 15. “Now that we are seeing historically conditioned binaries imploding and labels around gender becoming increasingly fluid, it’s more evident than ever how prophetic her vision has been from its very onset and how it has evolved and carried through in these last five decades. She pioneered a visual language that confronted gender, class, and sexual orientation within the higher realms of a painterly abstraction, bridging a sentient and materially rich abstraction with an active social awareness.”

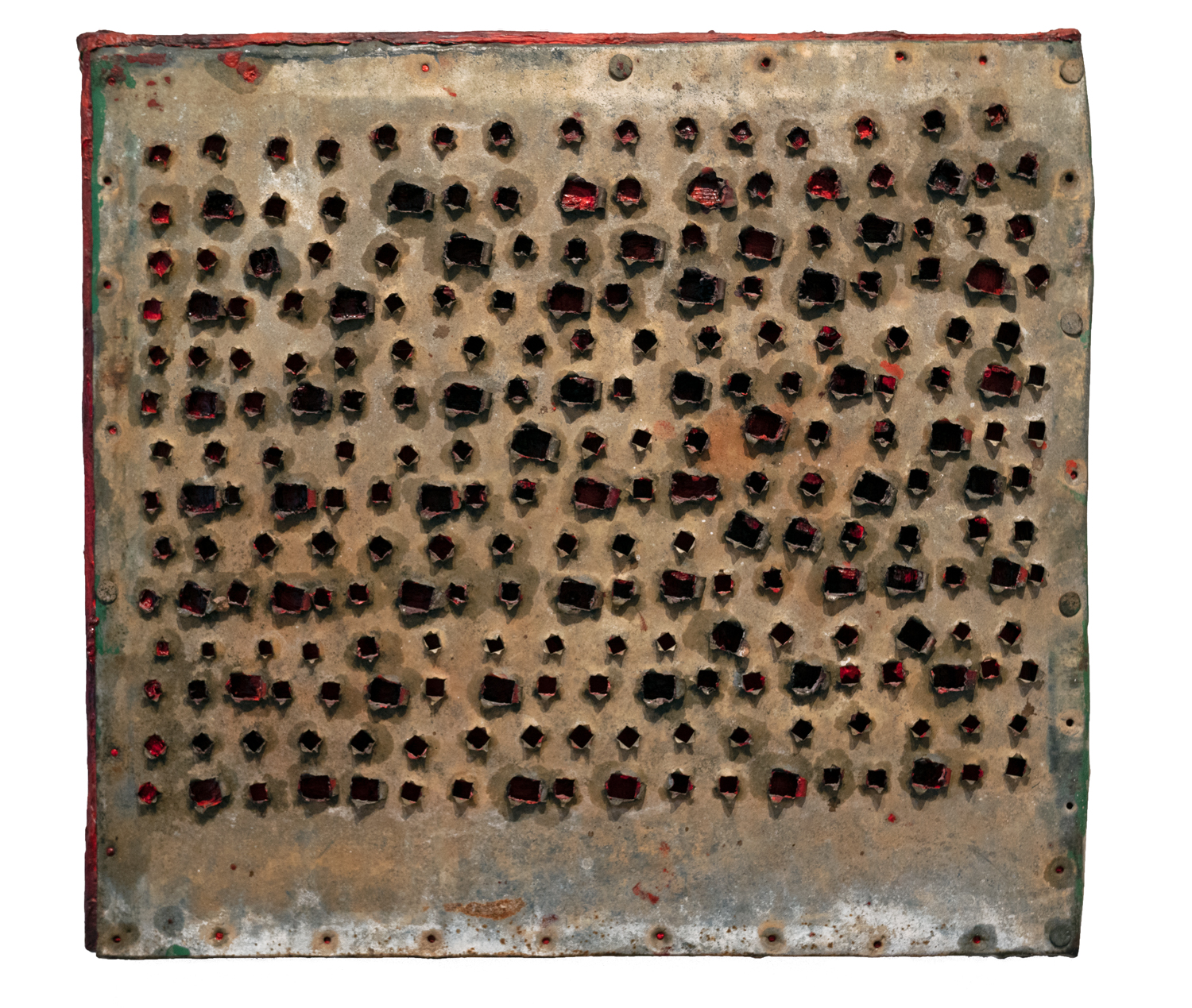

Harmony Hammond, Sieve, 1999, oil on metal and canvas.

CHRISTOPHER E. MANNING/©2018 HARMONY HAMMOND, LICENSED BY VAGA AT ARTISTS RIGHTS SOCIETY (ARS), NY/COLLECTION OF BARBARA JOHNSON AND RUTH GRESSER

Like many feminist artists in the early ’70s, Hammond rejected traditional painting because of its associations with (often toxic) masculinity. Choosing materials that related to women’s creative—frequently domestic—practices such as weaving, she intentionally challenged traditional distinctions between painting and sculpture, as well as art and craft, in what she called “expanded painting,” duking it out with the prominent male artists of the postwar era.

“I hate digital seamlessness,” said Hammond, who is now 75. She typically wears her sleek white hair pulled back, and is partial to cowboy hats. “My work has a survivor aesthetic, which has to do with piecing things together and making something out of nothing. It’s about rupture, suture, and endurance.”

Hammond, who was born and raised in Chicago, married a fellow art student from Millikin University in Decatur, Illinois. They moved to Minneapolis where she studied painting at the University of Minnesota in the early 1960s. In fall 1969, she and her husband moved to New York. It was months after the Stonewall Uprising in June, and downtown Manhattan had become a hotbed of experimental art making, liberation movements, and political activism. Within a year, Hammond separated from her husband, and became involved with the women’s movement.

“The women’s movement changed my life—and my art,” she said.

In 1970 she gave birth to their daughter, whom she raised as a single mother, while working part-time at the Brooklyn Public Library, attending weekly meetings with members of her feminist consciousness-raising art group, and making art.

Harmony Hammond, Dogon, 1978/2015, cloth, wood, and acrylic.

ERIC SWANSON/©2018 HARMONY HAMMOND, LICENSED BY VAGA AT ARTISTS RIGHTS SOCIETY (ARS), NY/COURTESY THE ARTIST AND ALEXANDER GRAY ASSOCIATES, NEW YORK

During that formative decade, Hammond established herself, along with a cohort of like-minded women including Miriam Schapiro, Faith Wilding, and Joan Semmel, as a pioneering feminist artist, activist, curator, and writer. In 1972 she was one of 20 artists—including Barbara Zucker, Nancy Spero, and Howardena Pindell—who founded A.I.R. Gallery, the first women’s cooperative gallery in the United States. In 1976 she co-founded the quarterly Heresies: A Feminist Publication of Art and Politics, with a collective including May Stevens, Joan Snyder, Pat Steir, Michelle Stuart, Joyce Kozloff, Mary Miss, and others. Heresies examined the social, critical, and financial structures of the art world through a feminist lens and created a discourse around women’s historical and contemporary artistic expressions. One edition, titled the “Lesbian Issue,” was devoted to lesbian art, artists, and culture, which until then had been invisible in mainstream media and arts circles.

In 1978 Hammond curated the groundbreaking “A Lesbian Show” at 112 Greene St. Workshop, the alternative space in SoHo that later became White Columns. The first exhibition of work by lesbian artists in the United States, it included pieces by Louise Fishman, Dona Nelson, Amy Sillman, and Kate Millett. The show was an energizing political statement about lesbian visibility, creating a community of artists who publicly identified as lesbian—and risked professional discrimination by doing so.

In the years that followed, Hammond, who left New York for New Mexico in 1984, sensed that despite the work she had continued to do since the ’70s there was still a void in terms of the visibility of lesbian artists. She began work on Lesbian Art in America: A Contemporary History, which took a decade to write and was published in 2000. It is the only art-historical text of its kind to date.

Like many artists from marginalized groups, Hammond produced scholarship out of necessity, providing a structure to examine not only her work but that of other queer feminist artists.

In Lesbian Art in America, she wrote, “We cannot afford to be silent or to let others decide what kind of art we may or may not make, nor let our creative work be ignored, ‘straightened,’ dehistoricized, decontextualized, or erased.”

Have things changed in the 19 years since the book’s publication? I told Hammond that I still see queer feminist artists fighting to have their work be recognized and remembered.

“That’s why I wrote Lesbian Art in America,” she replied, without missing a beat.

Installation view of “Harmony Hammond: Material Witness: Five Decades of Art,” 2019, showing five examples from her “Floorpieces” series, 1973, at the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, Ridgefield, Connecticut.

JASON MANDELLA/©2018 HARMONY HAMMOND, LICENSED BY VAGA AT ARTISTS RIGHTS SOCIETY (ARS), NY/COURTESY THE ARTIST AND ALEXANDER GRAY ASSOCIATES, NEW YORK

‘Material Witness,” the Aldrich show, is Hammond’s first institutional survey. Spread across two floors and a number of galleries, each housing a discrete body of work, it addresses the key aspects of a 50-year career that merges the formal experimentation of post-Minimalism with feminist and queer content.

Hammond has worked with a compelling diversity of materials, ranging from metal and wood to blood and burlap to rope and latex. Painted in deep blacks, creamy whites, sensual reds, and resplendent golds, the surfaces are often stained, incised, punctured, and scarred.

“Hammond has always shown a commitment to challenging the history of abstraction—and queering it,” said Alexander Gray, whose gallery represents her. “She does that with her materials, with imagery of scarring, sutures, wounds, orifices, seepage, leakage. She pushes against abstraction in the Malevich mold as a pure space, a spiritual, otherworldly device.”

In one room, next to a wall of windows, sit Hammond’s 1973 “Floorpieces,” colorful paintings on fabric coiled to resemble circular braided rugs. The installation here, conceived by Hammond and Smith-Stewart, presents the works alone; the walls nearby are blank. The artworks seem like paintings taken off the walls, or even very flat sculptures.

Some of Hammond’s most iconic works are her “Wrapped Sculptures” of the late ’70s and early ’80s. Wooden armatures swathed in fabric and covered with paint or latex, they are often anthropomorphic and slightly humorous. Some, like Kong (1981), reach out toward the viewer with thick, curved fingers; others hang flat on the wall, like the gold-painted Dogon (1978/2015), and still others, resembling short, plump ladders, lean against the wall and each other, as in Hug (1978).

“These works claim spatial dimensions reminiscent of her earlier series the ‘Presences,’ where abstract bodies that could be read as stand-ins for the women of Hammond’s consciousness-raising group at the time,” Smith-Stewart said. “These works celebrate women’s relationships as symbols of power.”

Though known for her use of the formal techniques of pure abstraction, Hammond’s survey highlights the way that text recurs throughout her practice. In her “Ledger” drawings (2015), which line a long hallway on the first floor, the gently leaning cursive is disquieting. One reads “Down girl, down girl, down girl”; another laments “Obsolete, obsolete, obsolete.”

Harmony Hammond, Inappropriate Longings, 1992, oil, acrylic, canvas, linoleum, latex rubber, metal gutter and water trough, dry leaves, triptych.

JEFFREY STURGES/©2018 HARMONY HAMMOND, LICENSED BY VAGA AT ARTISTS RIGHTS SOCIETY (ARS), NY/COURTESY THE ARTIST AND ALEXANDER GRAY ASSOCIATES, NEW YORK

In one of the panels of the large mixed-media triptych Inappropriate Longings (1996), the words “GODDAMN DYKE” are incised in gold latex next to fragments of floral-patterned linoleum. A casket-size metal trough full of dead leaves sits in front of the painting, suggesting violence. Taken together, these elements insert a lesbian presence into regions of rural America and the modernist painting field.

“The idea of what is usually buried and hidden beneath the surface, but is now revealed through materials, speaks to the painting I’m doing now,” Hammond said of Inappropriate Longings.

Since 2010, when she published a concise proclamation, titled A Manifesto (Personal) of Monochrome (Sort of), Hammond has focused mostly on iterations of near-monochromatic paintings. She describes her work of the last decade as “more condensed, with fewer materials in any given piece, and therefore, less narrative.”

The new works, though simple seeming, still chafe against the conventions of painting. They flaunt sutures, cracks, fissures, holes, scars, flaps, trailing ropes, and straps that emerge from the surface and dangle like entrails. Hammond has described her work as “performing queerly,” referring in part to the color shifts in the paint and the “fugitive” surfaces they create.

“Hammond is not one who rests; she changes elements,” Gray said. “Often things that look like found objects are not. The materials are transformed. Not just found, but repositioned, or collaged.”

These days, Hammond focuses less on writing, and more on her art. She attends environmental protests, women’s marches, and pride parades when she can, but she thinks of exhibiting as one of her primary forms of activism around visibility, erasure, and censorship.

“Exhibitions allow us to physically occupy space, so we are visible to queer and non-queer folks alike,” Hammond said. “I’ve always been engaged with voices and forces that have been buried, or covered up, and assert themselves from underneath the surface of things.”

[ad_2]

Source link