[ad_1]

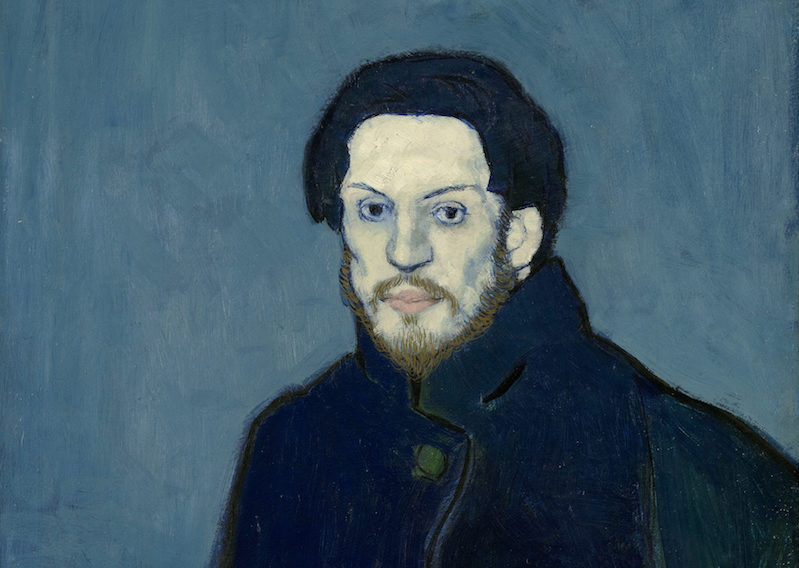

Pablo Picasso, Picasso Autoportrait, 1901.

© SUCCESSION PICASSO / PROLITTERIS, ZÜRICH 2018 PHOTO © RMN-GRAND PALAIS (MUSÉE NATIONAL PICASSO-PARIS) / MATHIEU RABEAU

Just an hour before Art Basel opened to invited guests on Tuesday morning in Basel, Switzerland, some 80 journalists convened at a press conference at the nearby Foundation Beyeler to hear details about an exhibition that will not open until next February—but which already sounds like it could be a blockbuster to end all blockbusters: “The Early Picasso: Blue and Rose Period.”

Sam Keller, the museum’s director, who was joined on stage with his chief curator, Raphaël Bouvier, and the artist’s granddaughter, Diana Widmaier-Picasso, an art historian, got things off to a crackling start by unleashing a series of superlatives. The show will be “by far the most ambitious our museum has organized to date,” he said; he termed Picasso “the most influential artist of the 20th century;” and he argued that the Rose and Blue moments are from “the most loved period of Picasso’s work by the general public.” Keller added, “We also expect to draw record numbers of visitors,” saying that attendance will likely outpace its marquee Monet and Gauguin shows. (Tickets go on sale in November for the affair, which runs next February to June.)

There are many Picasso shows each year, Keller said, but “ours will certainly be a once-in-a-generation experience,” maybe even a “once-in-a-lifetime” experience. “We will turn the entire Foundation Beyeler into a temporary Picasso museum,” he said, using the museum’s holdings from later periods and loans to offer a survey of the artist’s career.

Pablo Picasso, Nu sur fond rouge, ca. 1906.

PARIS, MUSÉE DE L’ORANGERIE, COLLECTION JEAN WALTER ET PAUL GUILLAUME © SUCCESSION PICASSO PICASSO / PROLITTERIS, ZÜRICH 2018

PHOTO © RMN-GRAND PALAIS (MUSÉE DE L’ORANGERIE) / HERVÉ LEWANDOWSKI

The Picasso blowout is a joint venture of the Beyeler with the Musée Picasso and Musée d’Orsay in Paris, where the show will open in a few months, on September 18, and run through January, after which it will venture to the Beyeler, where its focus will be expanded to include Picasso’s early moves into Cubism, a curatorial gesture made possible by the museum owning a study for the artist’s famed Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907), which is owned by the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Ernst Beyeler, who was close friends with Picasso, almost parted with that study, but his wife, Hilda Kunz, put her foot down. She “almost left her husband when he wanted to sell that work,” Keller said. “She famously put her suitcases on the painting. The painting leaves the house, I’m going to leave as well.” And so it remained in the collection.

Many other key Rose and Blue period works are also deeply ensconced in collections, whether public or private. “The works are rare, often very fragile, and very, very rarely lent,” Keller said, noting that they also tend to be popular at the museums that own them—another reason not to loan them. “Also,” he continued, “they are extremely valuable, both as cultural treasures of our civilization and also on the market.” By way of example, he motioned to a work on a screen behind him: Picasso’s Fillette à la corbeille fleurie (1905), which sold for $115 million last month in New York at Christie’s from the collection of Peggy and David Rockefeller. It will be in the show.

Pablo Picasso, Femme (Epoque des ‘Demoiselles d’Avignon’), 1907

Bouvier said that the Beyeler is still negotiating the terms of a loan for the important La Vie (1903) with its owner, the Cleveland Museum of Art—the first time that I can recall ever hearing a curator publicly disclosing the finer points of such a behind-the-scenes maneuver. Referring those assembled to a little maquette of the exhibition in the back of the room, he offered a précis of the Blue and Rose series, saying that in the former the “moving and profound images show Picasso confronting existential themes such as desire, destiny, and death,” while the “acrobats, artists, and circus performances” that define the latter may be read as stand-ins for Picasso.

The years between 1901 and 1907, which the Beyeler show will cover, marked a “period of instability and poverty,” Diana Widmaier-Picasso said. “At this time he often used twice his canvases because he didn’t have enough money to buy new ones.” She seemed thrilled about the exhibition. “My family has always been close to the Beyeler Foundation.” As it happens, she’s at work on a Picasso sculpture show right now, to open at the Villa Borghese in Rome in October. “It can warm you up for the show at the Beyeler,” she said.

It must be noted that such art press conferences tend to be, on average, a bit zestier in Europe than they are in the United States, and this one did not disappoint. One gentleman asked Widmaier-Picasso about her mother, Maya Widmaier-Picasso (the daughter of the artist and Marie-Thérèse Walter), and whether they are in contact. “How is she doing? She’s in her 80s now.”

Macarons—colored rose and blue, naturally—given out at the event.

ARTNEWS

“Yes, I see her every day,” Widmaier-Picasso said with a laugh. She’s doing well and is strong, even if she sometimes has trouble walking, she continued, noting pleasantly that she’s “still very focused on criticism. She has a power always to see what is wrong—in a picture, in a person.”

Another journalist wondered if “this exhibition is in some way a road show for the period, to validate it in the public market and in the auction market for possible recycling of some of this art in the deep collections . . . not maybe the masterpieces but lots of other pieces in the collection that might be subject for sale.”

“No,” Keller replied immediately. I can tell you exactly what the reason is. We have dreamt to do this exhibition for a long time.” He called it an “adventure together with our colleagues in Paris.”

“And if you are suggesting that we have any financial interest,” Keller said, “I can tell you the opposite is the case. This is the most expensive exhibition we have ever done. It will create the biggest deficit ever . . . we own no works from that period. I don’t know what other benefits than cultural such an exhibition should have to a museum.”

[ad_2]

Source link