[ad_1]

A 1512 self-portrait by Leonardo da Vinci at the Capitoline Museums in Rome.

DOMENICO STINELLIS/AP/SHUTTERSTOCK

Leonardo fever is taking hold this season. Last month, the Louvre opened its hotly anticipated Leonardo da Vinci retrospective, and timed tickets are already selling out fast. Meanwhile, over at the Castello di Rivoli Museo d’Arte Contemporanea in Turin, Italy, a Leonardo project of a different sort—meticulous copy of the $450 million painting Salvator Mundi by artist Taner Ceylan—is now on view as well. As excitement and intrigue surrounding the Italian master continues to build, ARTnews asked five experts and scholars one seemingly simple question: What is your favorite Leonardo work? Their responses, which follow below, may surprise you.

Leonardo da Vinci, Saint Jerome Praying in the Wilderness, begun 1483.

CLAIRE SELVIN/ARTNEWS

Carmen Bambach

Curator of drawings and prints, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Leonardo’s intensely spiritual painting of Saint Jerome Praying in the Wilderness (Vatican Museums) represents the summation of the great master’s powers of expression and dramatic storytelling. Ultimately, this unfinished picture also sums up his ethos as an artist who immersed himself in the creative process itself, experimenting and pursuing ineffable refinements ceaselessly, rather than commit to the completion of a final product.

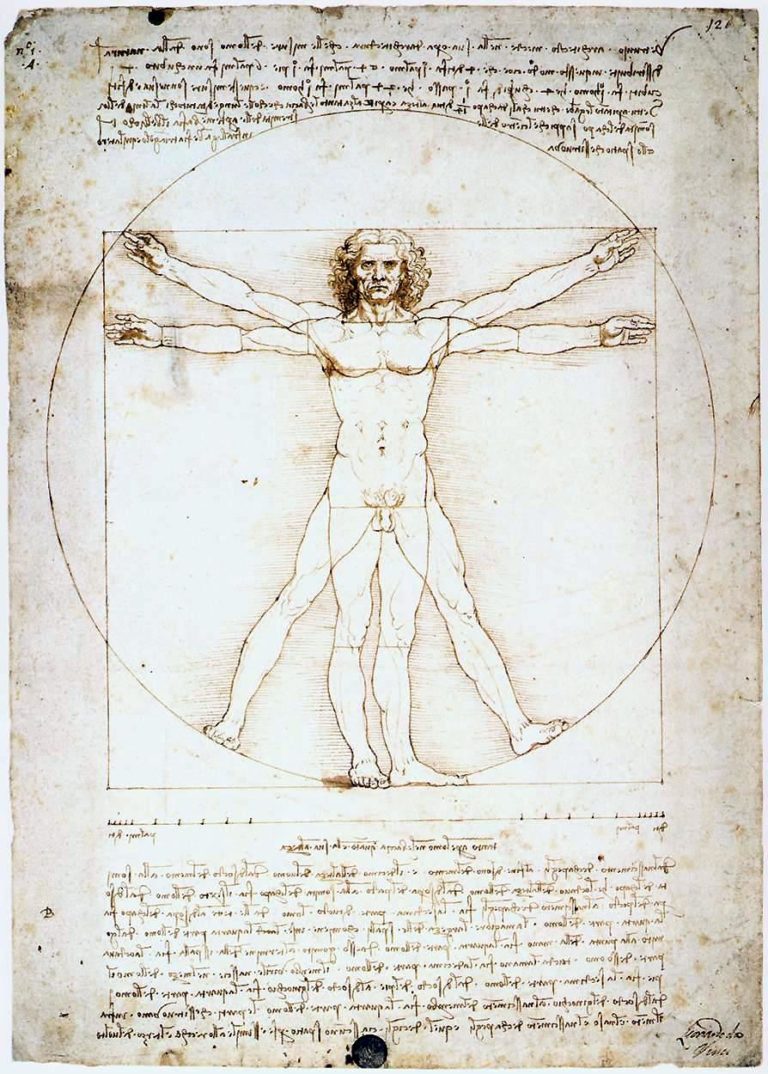

Leonardo da Vinci, Vitruvian Man, ca. 1490.

VIA WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

Matthew Landrus

Research fellow, Oxford University

Leonardo’s iconic Vitruvian Man drawing is rarely exhibited outside Venice, partially because it is so fragile and sensitive to the exposure to light. It is best, however, to see it in person, especially under raking light, to see the metal stylus incisions that outline the arms and legs, and mark divisions of the body, along the central axis, into six sections and seven sections. These are not visible in photographs. Leonardo corrected the Vitruvian six-foot division of the body in a circle and a square, noting that a body with these proportions would be seven feet tall. Drawn around 1490, this work is central to Leonardo’s approaches to proportion theories in visual and technical arts.

Leonardo da Vinci, Ginevra de Benci, ca. 1474-78, oil on panel.

COURTESY EVERETT COLLECTION/SHUTTERSTOCK

Carla Glori

Art historian

The portrait of Ginevra de Benci is my favorite artwork by Leonardo because Ginevra was a poetess. She can be defined as the antithesis of Mona Lisa. The sfumato creates mysterious shadows on the face of the Louvre muse, while the face of Ginevra is modeled with subtle veils and her porcelain-fine features reflect the splendor of the moon. The eyes are the mirror of her mental emotions. She has no mystery, but many secrets. Leonardo masterfully “portrayed the story” of this young woman trapped in the patriarchal Renaissance world and, on the reverse of the panel, he painted the symbolic sprig of juniper, a pun on her name, and the scroll with the inscription “VIRTUTEM FORMA DECORAT,” from which I formed 50 Latin anagrams that tell the story of Ginevra’s life.

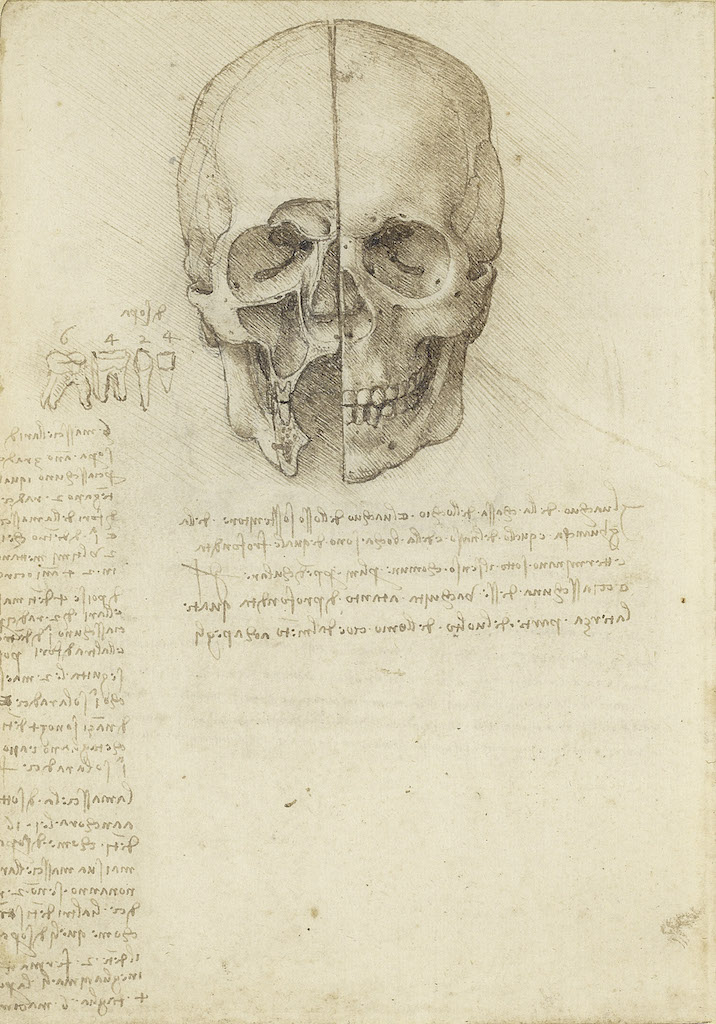

Leonardo da Vinci, The skull sectioned, 1489, traces of black chalk, pen, and ink.

ROYAL COLLECTION TRUST/© HER MAJESTY QUEEN ELIZABETH II, 2019

Martin Clayton

Head of prints and drawings, Royal Collection Trust

In April 1489, Leonardo obtained a skull, and sawed it open to study its internal structure. His aim was to understand how the brain worked—how we perceive the world through our senses, how we think, how we express emotions through our pose and facial expression. This small drawing (The skull sectioned) on a page from a notebook, was not intended for anyone else to see, but it is highly finished, detailed, and accurate, and embodies Leonardo’s wish to comprehend the scientific basis of life and art.

The Virgin with the Laughing Child, ca. 1460, terracotta.

©VICTORIA AND ALBERT MUSEUM

Francesco Caglioti

Art historian

I choose the terracotta group of the Virgin with the Laughing Child in the Victoria and Albert Museum [in London], in my opinion a [quintessential] work by the young Leonardo. It is, in fact, the only surviving sculpture by his hand, and perhaps the earliest among his masterworks. Because it was rediscovered as such only very recently, it allows us to take a new and fresh look at his art, capturing in the best way the great genius in the first steps of its astonishing development.

[ad_2]

Source link