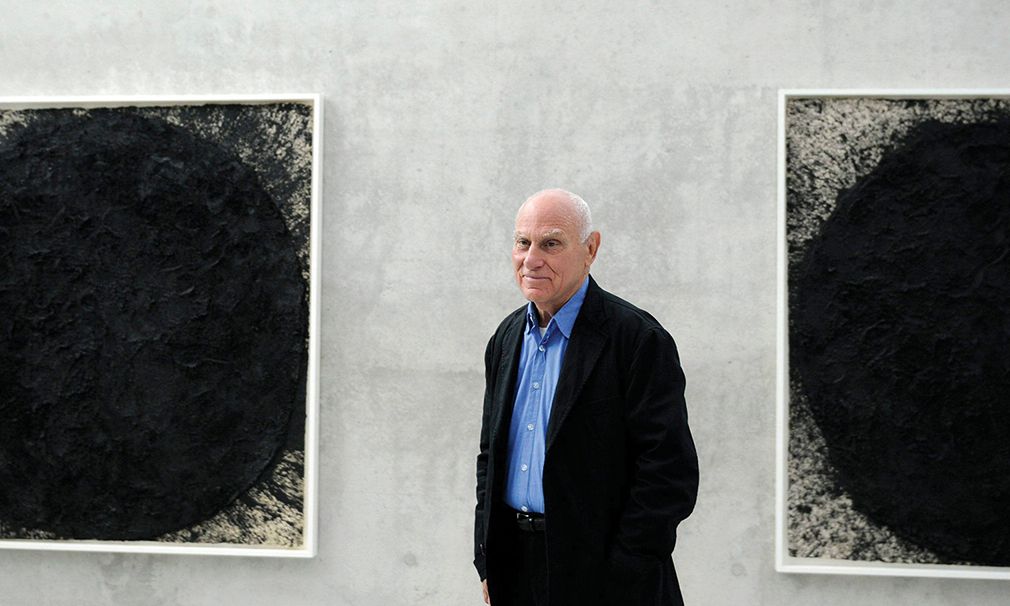

American artist Richard Serra (1938-2024) at his Kunsthaus Bregenz exhibition in 2008

Associated Press/Alamy Stock Photo/Keystone/Regina Kuehne

When Richard Serra (1938-2024) died in late March, the news rocked the art world and inspired a wave of memorials to his life, work and legacy. But with Six Large Drawings (until 18 May), his first show at David Zwirner’s London gallery, scheduled to open just two weeks later, the timing of his death also highlights the larger urgency surrounding how to ensure the proper display, marketing and management of the works artists leave behind.

“This is the last show conceived by Richard Serra during his lifetime,” a spokesperson for David Zwirner says of Six Drawings. “There have been no changes. Everything was in place before the artist’s passing on 26 March.” Among the minute details finalised in advance was the inclusion of a quote by Serra in a brochure detailing the works. The spokesperson adds: “His team had seen the space, and Richard Serra also had a maquette of the London gallery. He understood the two floors and the space.”

Even with Zwirner and Serra settling the details of the latest exhibition prior to the artist’s death, later decisions about his work and legacy will be made based on a breadth of moral, legal and financial considerations. In addition to his 11-year professional relationship with Zwirner, Serra actively worked with several contemporary dealers during his lifetime, including Gagosian and Cristea Roberts Gallery. But Serra’s lawyer John Silberman, who will act for the estate, confirmed that “no changes are planned from how Mr Serra’s works were managed prior to his death”.

Installation view of the final gallery show planned before Sierra’s death, Six Large Drawings, at David Zwirner, London

© Richard Serra. Courtesy David Zwirner. Photo: Anna Arca

The stewardship of an artist’s legacy, however firmed up it may be in advance, still comes with a complex and growing set of responsibilities.

“The role of estates is changing; for a while those managing bodies of work were primarily concerned with authentication and preservation of reputation, but increasingly we are seeing a move towards broader stewardship, including active market making,” says Yayoi Shionoiri, an art lawyer who has worked with such prominent artist estates as that of Chris Burden.

Whether an estate was being managed by individuals or legal structures (such as foundations or trusts) specifically set up to oversee posthumous matters, the authentication of works and the support of catalogues raisonnés were traditionally among the more public-facing challenges of the job. But a string of messy, high-stakes lawsuits has seemingly deterred many executors from assuming these responsibilities in recent years.

For example, the US collector Joe Simon-Whelan sued the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts in 2007, claiming that it had conducted a “20-year scheme of fraud, collusion and manipulation” to monopolise the market for the Pop artist’s works in part through the decisions of its authentication board. Although the parties settled out of court, the process took three years and required the foundation to amass nearly $7m in legal fees.

A more recent market-based legacy dispute erupted between the Helen Frankenthaler Foundation and its former board president Frederick Iseman last autumn. Iseman filed a complaint accusing the foundation and some of its current leadership of conflicts of interest and mismanagement, including that key board members were being neither active nor strategic enough in their handling of Frankenthaler’s work in the art trade. Although the foundation filed motions to dismiss Iseman’s lawsuit this February, the case was still ongoing when The Art Newspaper went to press.

Bespoke approaches will be needed if the parties responsible for upholding an artist’s creative legacy must also be involved in stewarding their commercial legacy. In instances where the artist has received a certain level of institutional attention and market demand before their death, the details of the arrangements tend to be more tightly delineated. Outside of such cases, however, even the clearest contractual agreements have their limits.

“If the artist did not have a market in their lifetime, I have found it is difficult to create one posthumously, contrary to popular belief,” says Chelsea Spengemann, of the Artist’s Foundation and Estates Leaders’ List (Afell) and the not-for-profit Soft Network.

As with much of the trade’s shift towards greater professionalisation and, to some extent, greater transparency, advice from estate experts generally leans towards artists putting as many of their wishes in writing as possible, from the relationship that they intended their work to have with audiences and the requirements for future displays of their works to any broader vision or missions they wanted to be fulfilled.

The decisions themselves and their timing often come down to tax issues, and they will not always be smooth running. In 2012, for example, the heirs of the Romanian American dealer Ileana Sonnabend encountered problems with the Internal Revenue Service over their inheritance of Robert Rauschenberg’s Canyon (1959), a work from his Combines series. Since the piece’s inclusion of a taxidermic bald eagle meant it could not be legally sold under US law, Sonnabend’s children listed its value as $0. But the service disagreed, appraising the work’s value at $65m and assessing $29.2m in estate taxes and $11.7m in late-payment penalties. A settlement between the parties led to Canyon being donated to New York’s Museum of Modern Art.

Lawyers, advisers and accountants are some of the intermediaries increasingly available (for a fee) to assist with estate planning for artists. Alongside them is a growing network of non-profit speciality organisations, including Europe’s Institute for Artists’ Estates and the US-based Artist’s Foundation. The Joan Mitchell Foundation in the US is also known to share resources on the subject.

Nevertheless, in a quick-moving market, the challenge of managing artists’ works and reputations is only growing steeper with time. “This work is really a public service since a high proportion of artist estates will never generate profit. The work is often done by a family member, who is often a woman, and often unpaid,” Spengemann says. “My hope is that with the greater visibility we now have around artist estate work will come real compensation for the workers and the artwork they have preserved.”