[ad_1]

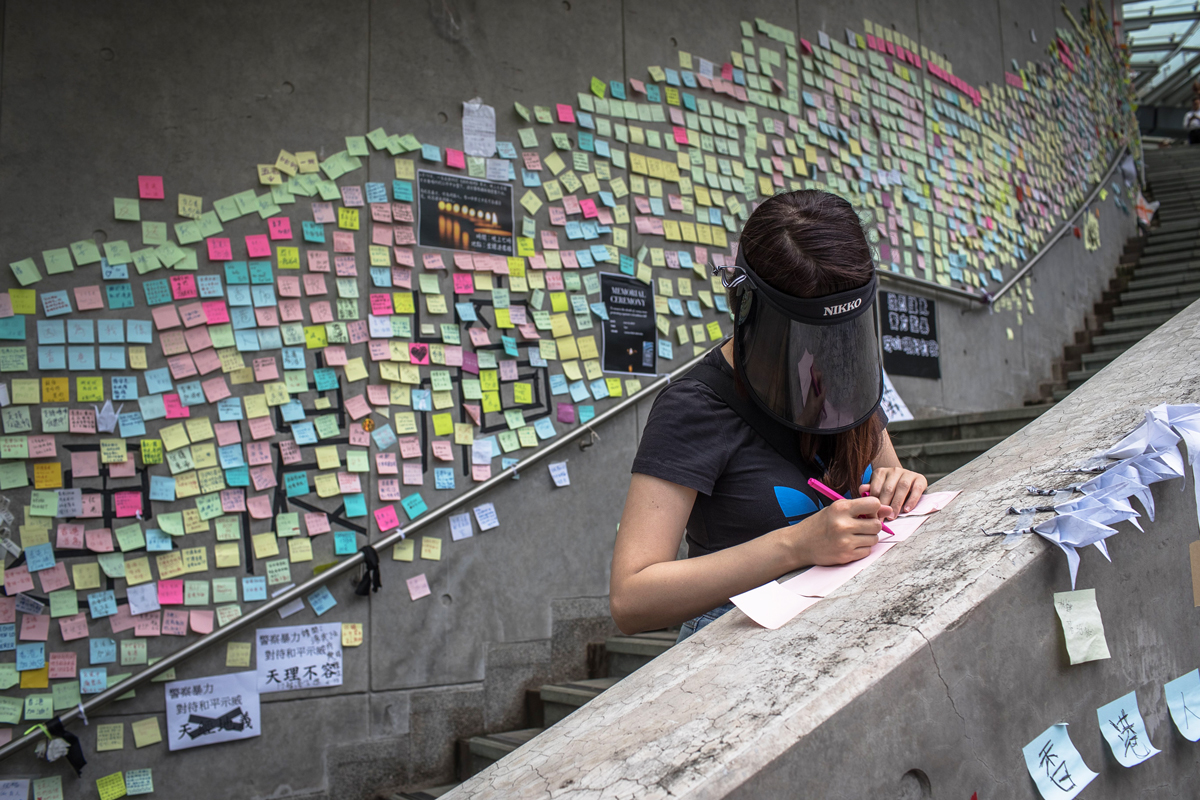

A woman writes a note next to anti-extradition banners and notes taped to a wall by protesters near the Legislative Council in Hong Kong.

ROMAN PILIPEY/EPA-EFE/SHUTTERSTOCK

After more than a week of protests in Hong Kong culminating in crowds of nearly 2 million on Sunday, Carrie Lam, Hong Kong’s chief executive, issued an apology on Tuesday, stating that she has postponed consideration of a proposed extradition law indefinitely. The legislation would allow those accused of crimes in Hong Kong to be extradited to mainland China, where an opaque judicial system is fraught with human-rights violations. Though this apology was not sufficient to silence calls from some for Lam to resign, it was a major victory for protesters concerned about encroachment on personal freedoms by the central government in Beijing.

As with the Umbrella Movement in 2014, which centered on demands for more free and open elections, artists have been key participants in the demonstrations that have filled the streets of Hong Kong. On June 12, the day the legislation was supposed to be voted on, more than 100 arts organizations, including many major galleries, participated in an “art strike,” shutting their doors and freeing their staffs to join the demonstrations.

The strike was the result of an open letter circulated by the Hong Kong Artists Union (HKAU), a group of 300 anonymous members who have been agitating for change in the Hong Kong art scene since its founding in 2016. From the nonprofit alternative space Para Site to the commercial Lehmann Maupin gallery, which is headquartered in New York, dozens of arts organizations closed for the day. Tai Kwun Contemporary remained open only to those who had pre-purchased tickets for its current Murakami exhibition; no one else was permitted to enter. The Hong Kong Art Center, which is located close to the Legislative Council, where the vote was to occur, stayed open to offer assistance to the crowds, providing water and a place to recharge phones.

Posters and placards bearing photos of Hong Kong Chief Executive Carrie Lam and police commissioner Stephen Lo Wai-chung, placed by protesters outside the Legislative Council in Hong Kong.

VINCENT YU/AP/SHUTTERSTOCK

According to Christy Li, the head of communications at Asia Art Archives, one of the groups that closed in solidarity, there was never a question about participating. “As an independent organization, we value a diversity of opinions and, most importantly, we support our team’s right to express their views in the way they prefer,” Li said. “We believe art is knowledge, and that it cannot be removed from its social contexts.”

Ka Ying Wong, a spokesperson for HKAU, emphasized that the strike represented only a partial victory for the group. “I won’t claim that we were successful because most of the places that closed didn’t make an announcement that they did this because of the extradition law,” she said. While many merely said that they were closed due to the crowds or inconvenience, few actively spoke out against the legislation. “But we appreciate that they did not punish their staff who wanted to join the strike,” Wong added. “Their not-opposing attitude is already a kind of support.”

HKAU resembles New York organizations such as Decolonize This Place and P.A.I.N., and it has been staging similar acts of resistance in response to issues related to museum funding and leadership. For example, in March, the group protested when Para Site announced that its latest exhibition would be sponsored by G4S, a British global securities service that runs immigrant detention centers and prisons where there have been allegations of abuse. HKAU sent a letter to Para Site and one artist gave a speech during the opening. The next day, the group received a letter of apology from Para Site director Cosmin Costinas, saying that the organization would no longer accept G4S money and that it would remove the company’s logo from exhibition catalogues and promotional materials. Like W.A.G.E. in the United States, the Artists Union has also pushed for fair payment for artists.

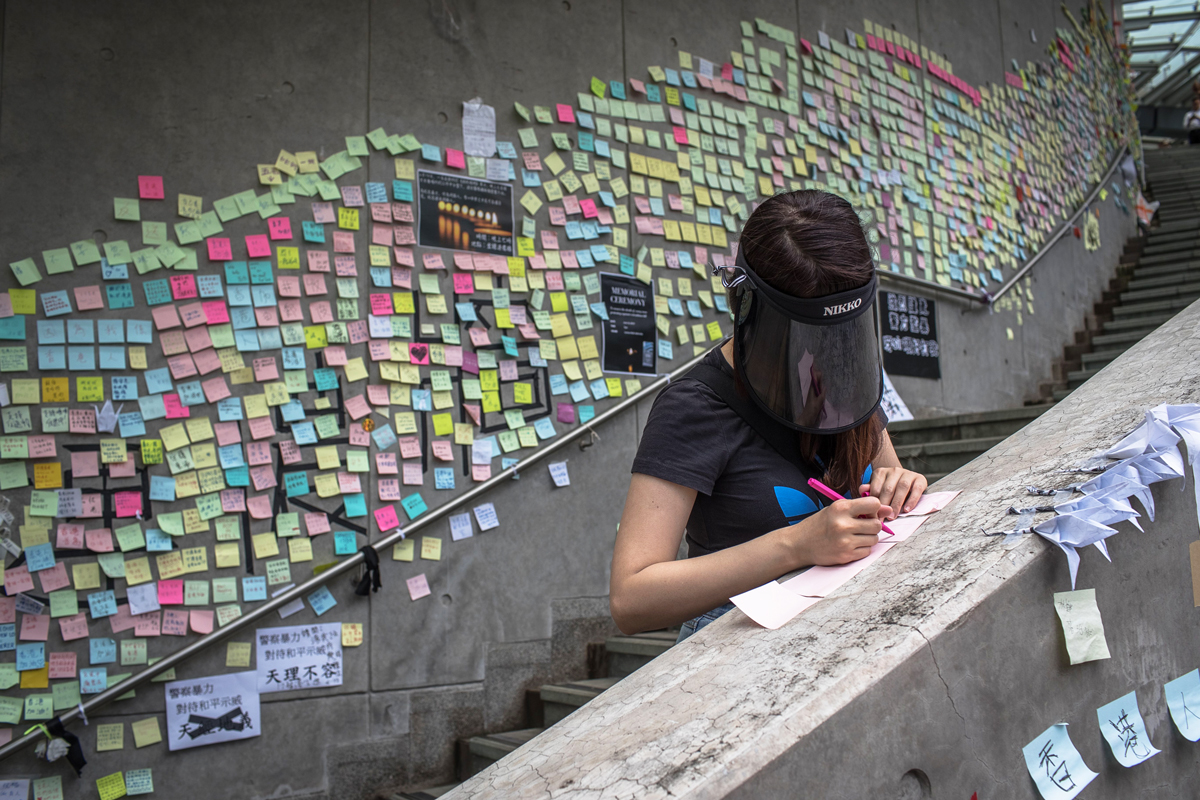

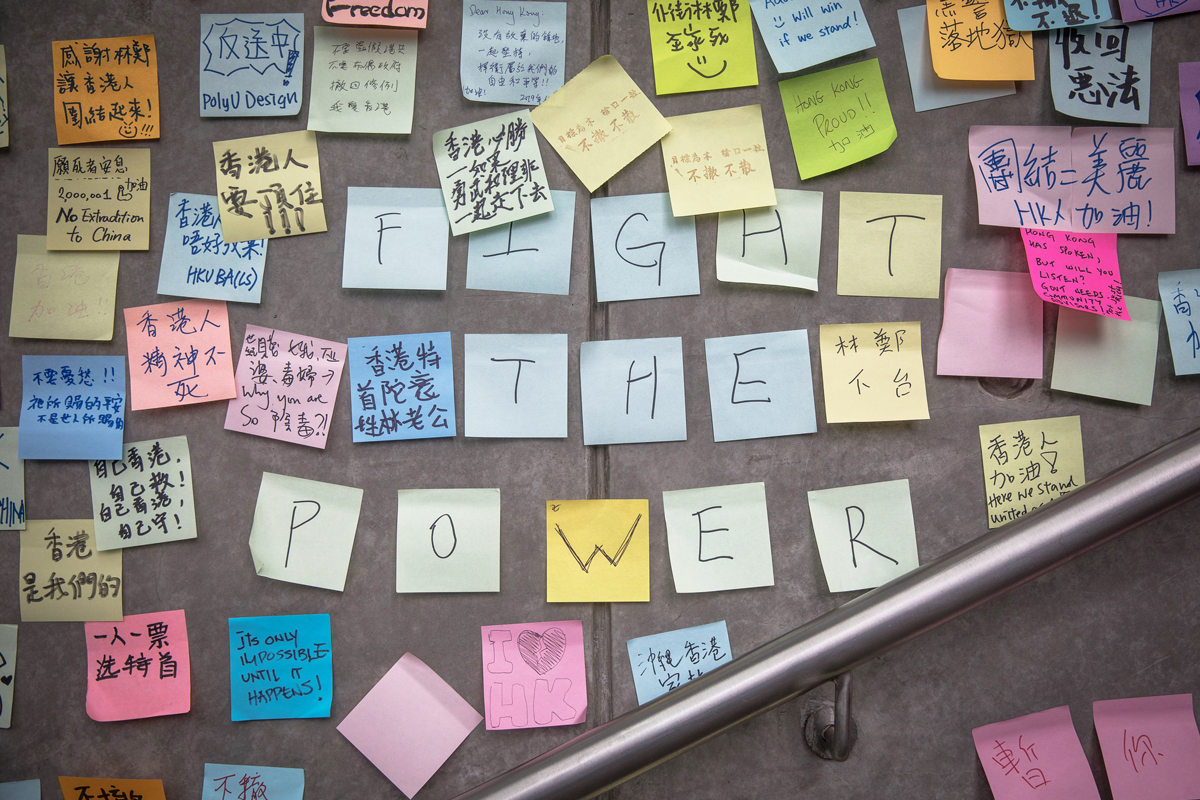

Pieces of paper taped to a wall near the Legislative Council in Hong Kong by protesters demanding the resignation of Hong Kong Chief Executive Carrie Lam.

ROMAN PILIPEY/EPA-EFE/SHUTTERSTOCK

For now, though, national politics is HKAU’s focus. “There are so many other corrupt things that we need to fix,” Wong said, “but at this moment we must focus on the anti-extradition movement, because after all, freedom of speech is the most important thing in creativity and the making of art.”

HKAU members been busy in recent weeks making banners, T-shirts, and props for the ongoing demonstrations—while the hugest numbers have turned out for weekend protests, a few hundred demonstrators have said they will continue to gather near the Legislative Council until the legislation is withdrawn. The group is also creating an archive of protest materials and ephemera that it plans to present in the exhibition “The Bicycle Thieves,” which opens June 28 at Para Site. Curated by Hanlu Zhang, the show focuses on the “bicycle sharing platform” as a means of addressing “labor conditions against the backdrops of technological development, economic transitions, as well as political aggressions.”

Many artists and arts professionals who are not HKAU members have also been extensively involved in the recent activism. For example, artist Sampson Wong, who was active in the Umbrella Movement, was photographed holding a banner reading “The People’s Will is Here,” which was widely shared by news media. Many artists are organizing their own groups to create banners and other props to bring to the protests, Wong said. “The atmosphere is very democratic. Not just professional artists—everyone is making their own things. I think some of the most impressive creativity comes from the online community. The most humorous and playful ideas often come from a more general public, so I think artists are not really unique or special in this truly populist movement.”

[ad_2]

Source link