[ad_1]

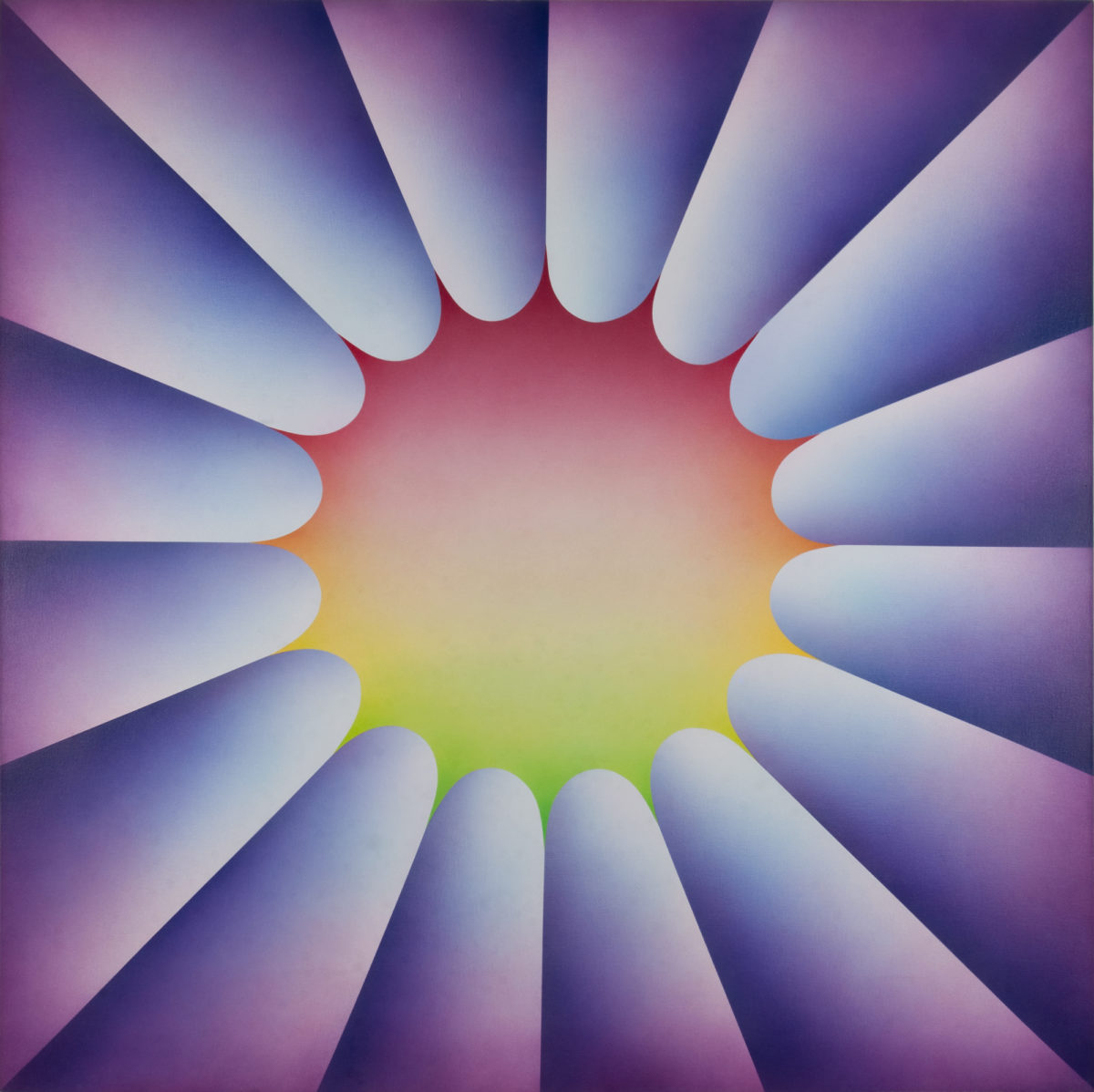

Judy Chicago, Through the Flower, 1973, sprayed acrylic on canvas.

©JUDY CHICAGO/ARTISTS RIGHTS SOCIETY (ARS), NEW YORK/PHOTO: ©DONALD WOODMAN AND ARTISTS RIGHTS SOCIETY (ARS), NEW YORK/COURTESY THE ARTIST; SALON 94, NEW YORK; AND JESSICA SILVERMAN GALLERY, SAN FRANCISCO/IMAGE: COURTESY FINE ARTS MUSEUMS OF SAN FRANCISCO/COLLECTION OF DIANE GELON

Forty years after her landmark installation The Dinner Party (1974–79) made its debut in San Francisco, Judy Chicago will get a homecoming of sorts in the largest exhibition of her work to date—a full-dress retrospective set to open next year in the Californian city’s de Young Museum. The artist announced the exhibition, which will open in May 2020, on Friday night at a celebration for her 80th birthday held in Belen, New Mexico, where she lives.

Chicago is considered among the foremost artists to come out of the Feminist Art Movement of the 1970s, in which she played a key role through her work in developing consciousness-raising arts education programs. (They took place first at Fresno State, then the California Institute of the Arts, and at the Women’s Building throughout the early ’70s.) Her Dinner Party launched her to international stardom, though the de Young exhibition will look at the full breadth of Chicago’s work, which has spanned five decades and taken the form of paintings, ceramic sculptures, drawings, prints, and performance work.

“I’ve been working for a long time,” Chicago told ARTnews. “I used to say I hope lived to long enough to come out from behind the shadow of The Dinner Party.”

Chicago credited this contemporary interest in her work to its appearance in several shows across the Getty Foundation’s inaugural Pacific Standard Time initiative in 2011, which focused on Los Angeles’s importance to postwar American art history. Last year during Art Basel Miami Beach, the Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami mounted a sizable survey of work of around 40 works. The de Young show will be more than twice as large, with about 100 pieces.

The artist is also readying an exhibition of a new series, titled “The End,” that will open in September at the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington, D.C. The new work will focus on death and mortality, and examples from the series will be included in the de Young retrospective.

Claudia Schmuckli, who is organizing the Chicago retrospective at the de Young, said that while The Dinner Party may represent the “pinnacle” of the artist’s career, Chicago has produced much more art that is worthy of study. “Her importance within the history of art has been undeniably established, but a lot of people aren’t familiar with full extent of her practice,” Schmuckli said.

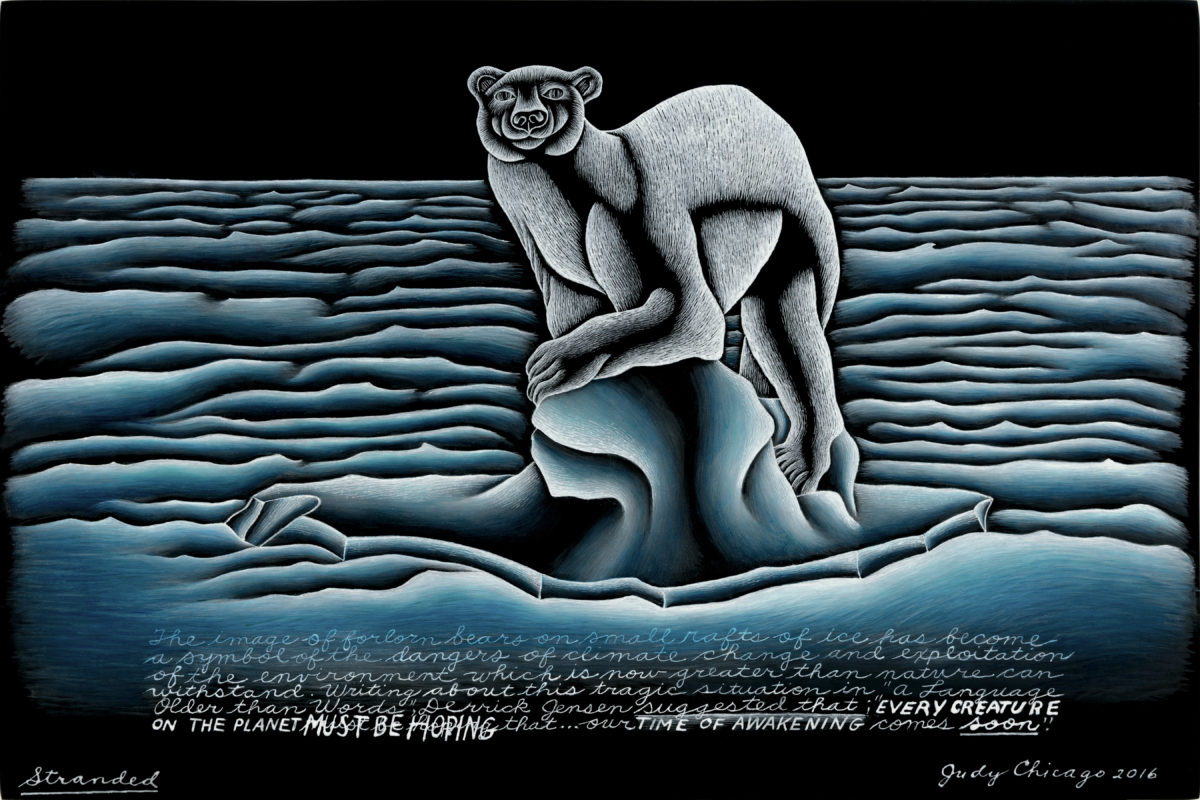

Judy Chicago, Stranded, 2016, kiln-fired glass paint on black glass.

©JUDY CHICAGO/ARTISTS RIGHTS SOCIETY (ARS), NEW YORK/PHOTO: ©DONALD WOODMAN AND ARTISTS RIGHTS SOCIETY (ARS), NEW YORK/ARTWORK: COURTESY THE ARTIST; SALON 94, NEW YORK; AND JESSICA SILVERMAN GALLERY, SAN FRANCISCO/IMAGE: COURTESY FINE ARTS MUSEUMS OF SAN FRANCISCO

Those looking to see The Dinner Party will have to travel to New York, however. That installation—an epic sculptural piece in the form of a triangular table laid out with place settings for important female figures from throughout history, from Boudica to Frida Kahlo—is on permanent display at the Brooklyn Museum, and it will not travel to San Francisco. Schmuckli said she felt that it was important the show was “not completely centered around The Dinner Party,” though it will include related works.

Examples of lesser-known parts of Chicago’s oeuvre to be addressed in the exhibition including her early experiments with color theory, her feminist reinterpretations of Minimalist aesthetics, figurative paintings about power and gender, fiber works, tapestries, and canvases about ecological destruction and extinction.

Asked to point to work that she hoped would be seen anew by visitors to the de Young exhibition, Chicago mentioned “The Holocaust Project,” a 1985–93 series, produced in collaboration with her husband Donald Woodman, that ponders notions of power and powerlessness as it relates to the persecution of Jews during World War II. “It echoes what’s happening now, again, and it’s prescient, unfortunately,” Chicago said. “I think there’ll be a lot of discoveries in Claudia’s show.”

[ad_2]

Source link