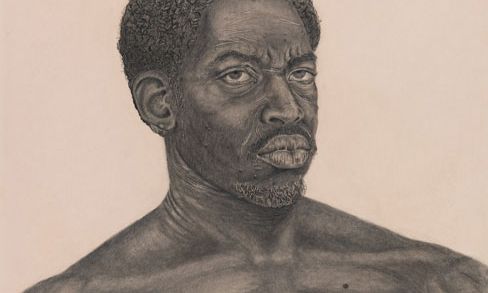

Cedric Adams's Just How I Feel (1972) features in Black American Portraits

This timely book brings to the fore Black American portraiture dating from around 1800 to the present day, featuring artists such as Kerry James Marshall, Alice Neel, Lorraine O’Grady, Catherine Opie and Amy Sherald. The selection of around 140 works from the permanent collection of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (Lacma) encompasses emancipation, scenes from the Harlem Renaissance, portraits from the civil rights and Black Power eras, multiculturalism of the 1990s and the Black Lives Matter phenomenon. The book accompanies an exhibition that was launched at Lacma in 2021 and is touring to Spelman College Museum of Fine Art in Atlanta (until 30 June). Both pay homage to the 1976 Lacma exhibition Two Centuries of Black American Art which was billed as the “first comprehensive survey of African American art”, covering the period 1750 to 1950.

This analysis spans 400 years of American culture, focusing on key objects in the Princeton University Art Museum collection that feed into current debates on issues such as race, gender and the environmental crisis. “The book is grounded in the understanding that the meanings of objects change over time, in different contexts, and as a consequence of the ways in which they are considered,” says a publisher’s statement. The art historian Kirsten Pai Buick focuses on the enslaved potter David Drake who wrote the word “Concatination” on a jar in 1834, a reference to the shackles that held slaves in bondage. Other enlightening items include a photograph taken around 1883 by Luke C. Dillon of the ruins of the slave quarters at George Washington's home. The book accompanies a touring exhibition which is currently at the Georgia Museum of Art (until 14 May).

The author Caroline Riley, a research associate in the department of art and art history at the University of California, explores how art was employed as a tool of cultural diplomacy before the Second World War. As economies collapsed worldwide during the politically turbulent 1930s, New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) collaborated with the US Department of State for the first time to deploy works of art as “diplomatic agents”. A press release for the exhibition, held at the Musée du Jeu de Paume, outlines works shown by artists such as Winslow Homer, Childe Hassam and John Singer Sargent.“MoMA Goes to Paris in 1938 explores how, at a time when the concept of artworks as‘masterpieces’ was very much up for debate, the exhibition expressed a vision ofAmerican art and culture that was not only an art historical endeavour but also a formulation of national identity,” says a publisher’s statement.

Many of the Abstract Expressionist women who forged a radical new painting style alongside their male counterparts have been overlooked. This publication is an analysis of the contributions made by key artists such as Elaine de Kooning, Grace Hartigan and Dorothy Dehner who “remained largely in the shadow of their male counterparts”, says a publisher’s statement. All of the works are drawn from the collection of the former commodities trader Christian Levett who writes in the introduction: “[These women] managed to elbow their way through extreme social and financial headwinds to become equally some of the greatest artists of the period despite the fact that many of their male counterparts ultimately became infinitely more famous—at least, until now.” Levett has loaned several works to the Whitechapel Gallery in London for the exhibition Action, Gesture, Paint: Women Artists and Global Abstraction 1940-1970 (until 7 May).