[ad_1]

The veteran Cincinnati-based art dealer Carl Solway, who supported visionary artists for more than 50 years, died in Ohio. The cause was cancer, his family said; he was 85.

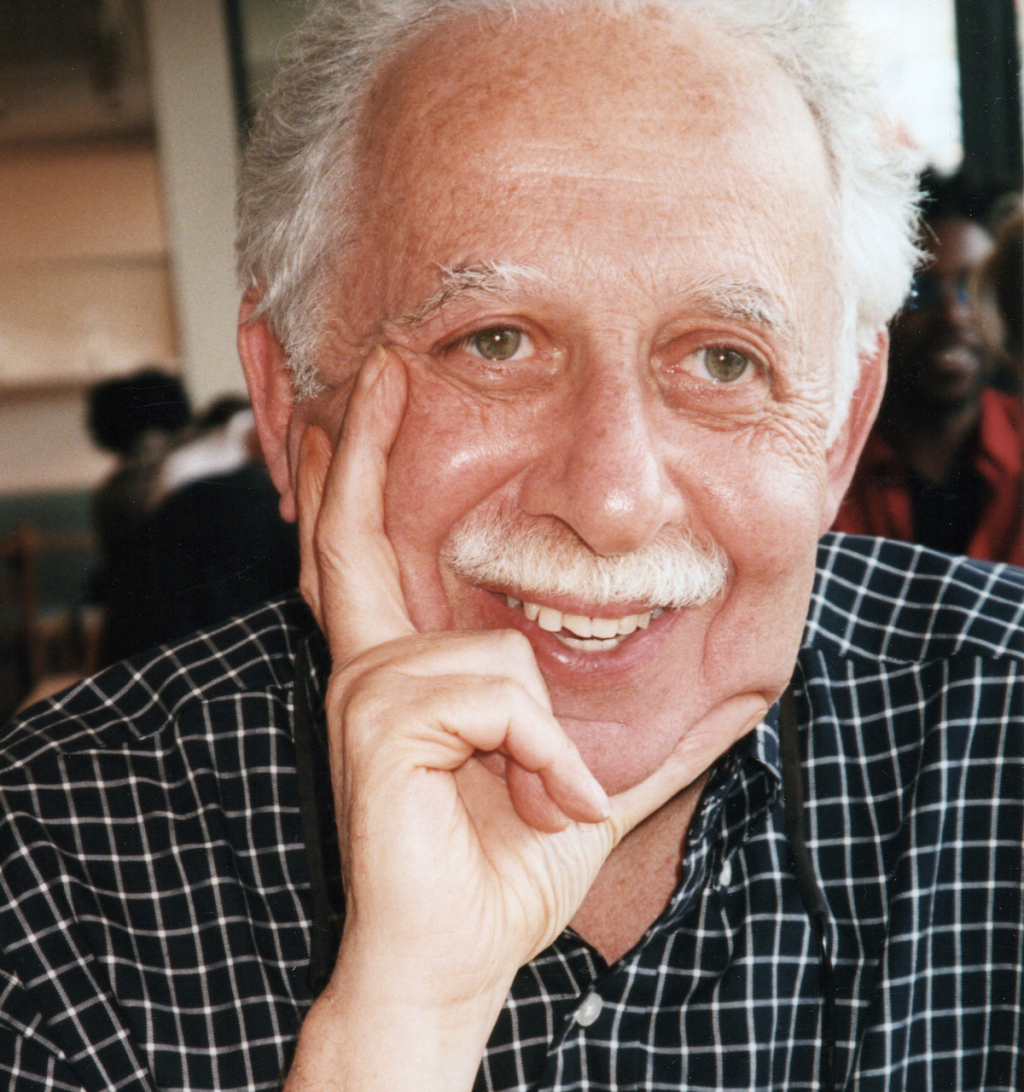

Instantly recognizable for his bespectacled, wild-haired Einsteinian look, Solway not only served the Cincinnati region; he also had a substantial impact on the art of the 20th century, and on the careers of trailblazing figures like John Cage, Buckminster Fuller, Ann Hamilton, Nam June Paik, Aminah Robinson, Joan Snyder, and many other major artists.

“He loved artists,” Hamilton said in an email. “He trusted what they do, was up for any adventure. He took as many risks as any artist—the next words out of his mouth were always ‘what if.’”

Carl Ellis Solway was born in Chicago on January 12, 1935. His father, a pharmacist named Arthur Maltz, died when Carl was just four years old, and his mother moved to Cincinnati for what his family called “an arranged marriage” to Harry Solway, who owned a furniture store. Carl’s upbringing, his son Arthur said via email, was “merchant class, Jewish, and all that came with it in those days.”

Solway went to high school in Cincinnati before attending the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, graduating in 1956.

He married his high school sweetheart, Gail Fisher (now Forgerg), and together they opened Flair Gallery in Cincinnati in 1962. At the time, the gallery focused on local artists and important prints. He placed a Kandinsky print portfolio in the collection of the Cincinnati Art Museum in 1965, Solway’s first sale of many to a public institution.

In 1967 Cage came to the University of Cincinnati to teach music as a visiting composer, and was introduced to Solway. The two struck up a friendship that would have a significant effect on them both.

Arthur Solway—himself a retired art dealer who worked for leading galleries in both New York and Shanghai—said in an interview that Cage “would come play chess with Carl on Saturdays, and he looked around one day and said, ‘You have a nice gallery here, but all the artists are dead.’ ”

As Carl said later, “I decided to focus on the classical work of my own generation. All the really great art dealers of the past are those who fought for artists of their own generation.” In 1969 he published Cage’s first work of visual art, a complex multiple dedicated to his recently deceased mentor and friend Marcel Duchamp. It took the form of eight constructions, each one comprising eight plexiglass panels, composed with the aid of coin tosses. These panels could be shuffled and changed for display in a custom stand. They called the sets “plexigrams,” and titled the overall work Not Wanting to Say Anything About Marcel.

It was a foray into a wider art world, if a tentative one. The next year, after the breakup of his marriage with Forberg, Solway changed the name of the business to Carl Solway Gallery and participated in the first Art Basel fair in Switzerland. But like many dealers of the time, before art fairs proliferated and the Internet was developed, Solway had to take his stock on the road to make enough sales to survive.

The New York dealer James Cohan, a nephew of Solway’s, fondly remembers a visit of the rolling gallery. Solway traveled with his assistant Jack Bolton, who later became the curator for Chase Manhattan Bank’s collection, Cohan said. “They rolled up to our house in Cleveland in a VW van full of art. They installed an exhibition in my family’s finished basement (tiki bar and all) and had an opening and saw clients for a weekend.

“I distinctly recall an early very simple George Rickey sitting on the bar, a Miró scroll, and a falling figure by Ernst Trova . . . in addition to Op art paintings.” Cohan, then 11, was dazzled by the objects. But more than that, he said, Solway and Bolton “described ideas which made the objects come alive. It was at that moment in my own basement, as they were furiously installing, that I thought: I could do this.”

Some 46 years later, Cohan sold three of the complete editions of Cage’s plexigram work, to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the Seattle Art Museum, and a private foundation. “The price [at which] we sold each suite . . . probably far exceeded the entire year’s worth of business in 1971” at Solway’s gallery, he said.

One of Solway’s great gifts was his ability to realize the market possibilities for strong artistic concepts. After meeting Buckminster Fuller in 1973 through Cage, according to Arthur Solway, his father developed a market for Fuller’s objects based on the architect’s rich store of ideas, disseminating them to a wider audience and raising needed funds. At the time they met, which began a decade-long partnership, Arthur said, “Bucky was traveling around giving 350 lectures a year because he needed money to support his architecture and design studio.”

A similar working relationship, one that lasted 20 years, was forged with Nam June Paik beginning in 1983. It was largely through Solway’s efforts that Paik was able to build a material bridge from the realm of ideas to the installations, robot sculptures, and other objects that sustained the artist through the end of his life.

Hamilton, who was introduced to the dealer by the artist Judy Pfaff, worked with him on an edition published in 2014. “Carl was always patient but also always encouraging me to make more ‘portable art,’ work people could buy, and to work with the material vocabulary of the ephemeral installations,” she said.

Hamilton credited Solway with far more than a knack for sales, however. “We talked about Emmett Williams, John Cage, the Fluxus materials we both so love,” she said. “There were emails that would arrive—the subject line always read, ‘Questions from Carl.’ ”

The history of Solway’s galleries reflects his commitment to the local as a vital part of the larger mainstream. In 1972, even as he was growing his eponymous gallery, he opened Not in New York Gallery to focus on Midwestern artists. In 1974, while continuing to run the Cincinnati spaces, he joined with Chicago’s Phyllis Kind and San Francisco’s Ruth Braunstein in a joint New York gallery venture that ran for four years at 139 Spring Street in SoHo.

And like many of the most important galleries of the past, Carl Solway Gallery was a family affair. In addition to inspiring Arthur and Cohan to become dealers, Carl’s current wife, Lizi, was with the gallery from 1979 to 1992. Another son, Michael, ran his own space in Los Angeles and then became managing director of the Cincinnati gallery in 2011, where he continues today.

In addition to those in the art business, Solway is survived by another son, Ned; three sisters; three daughters-in-law; five grandchildren, and one great-grandchild.

Charles Desmarais is the art critic for the San Francisco Chronicle. From 1995 to 2004, he was director of the Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinnati, which Carl Solway supported. The two were longtime friends.

[ad_2]

Source link