[ad_1]

What do you want from a painting? This was the question that John Baldessari considered when, in the mid-1960s, he painted What Is Painting (1966–68), a work currently on view at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. It takes the form of a beige monochrome canvas, along with some text bearing the work’s name and the following statement, printed in text so uniformly rendered, it appears to have been placed there by a machine: “DO YOU SENSE HOW ALL THE PARTS OF A GOOD PICTURE ARE INVOLVED WITH EACH OTHER, NOT JUST PLACED SIDE BY SIDE? ART IS A CREATION FOR THE EYE AND CAN ONLY BE HINTED AT WITH WORDS.”

Even though What Is Painting does not contain anything visually offensive, it is an assault. It’s a work that forces viewers to consider not what lies within the context of the canvas, but what lies outside it—an assemblage of hefty ideas about art itself. Pictures are not enough, Baldessari seems to suggest. Concepts matter equally, if not even more.

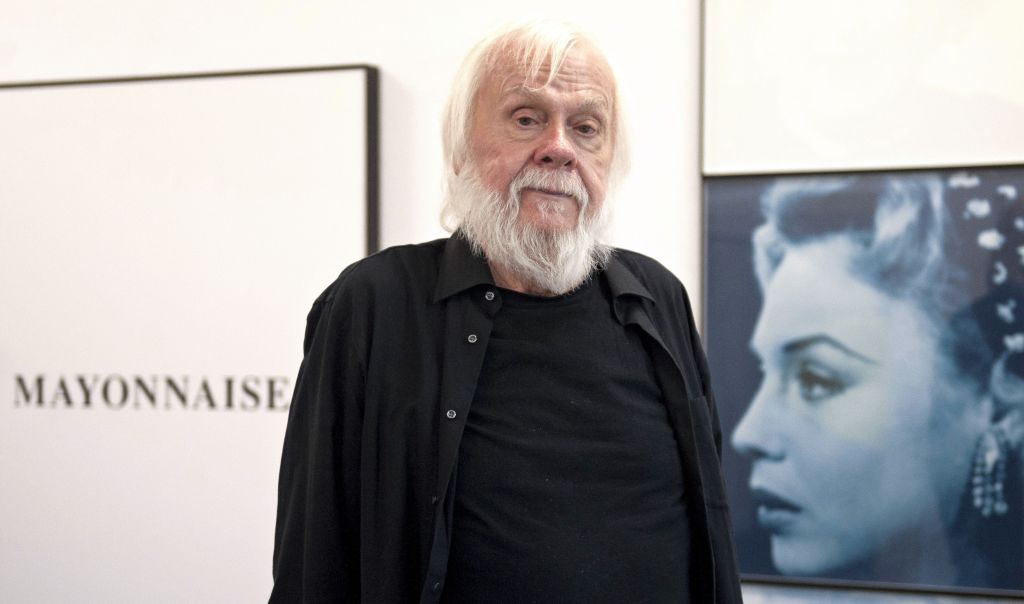

Baldessari, who died at 88 years old on Saturday, became one of the most influential contemporary artists of the past half-century for an oeuvre filled with works like What Is Painting. One of the leading artists part of a movement known as Conceptualism, he pioneered a style that placed an emphasis on ideas over images, crafting works that scrambled traditional notions about what was considered high art and questioning stereotypes about authorship. Working with photographs, text, and appropriated materials, he spent decades upending and rethinking what art could and should do.

The Californian artist’s work was one of dry puns, arty jokes about art, and jabs at high-minded lines of thinking that have pervaded art history for centuries. But Baldessari never thought about humor as being his primary mode of expression. “I don’t try to be funny,” he told the artist David Salle, a longtime friend and former student of his, in a 2013 conversation published by Interview. “It’s just that I feel the world is a little bit absurd and off-kilter and I’m sort of reporting.”

Using visual tomfoolery to get at serious ideas was a longstanding strategy of his. In 1967, Baldessari crafted one of his most memorable works, Wrong (1967), for which the artist stood in front of a palm tree—his six-foot-seven-inch-tall body does not even come close to approaching its fronds—and posed for a camera. Baldessari had thought of how photography manuals frequently urged people not to shoot each other in front of trees—it could look like a plant was sprouting from one’s head. Yet Baldessari deliberately wanted a bad image, and so he produced one. Beneath the image, which is reproduced on blank canvas, is one word: “WRONG.” As for the picture itself, it’s deliberately amateurish and low-quality, a sight for sore eyes.

When Baldessari made Wrong, photography was just starting to be considered an artistic medium. If a picture were to be considered art at the time, it certainly wouldn’t look like this—it would be highly finessed and neatly composed. He was among those who helped moved photography into the fine-art sphere, into a more conceptual realm. As he put it in the conversation with Salle, “I could never figure out why photography and art had separate histories. So I decided to explore both.”

If one is left wondering why, exactly, the photograph was wrong, that was also Baldessari’s point—he frequently questioned the tenuous relationship between an image and the text describing it, in the process attempting to drain language of metaphorical meaning. This was a sensibility best glimpsed in I Will Not Create Any More Boring Art (1971), in which Baldessari had students at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design in Canada repeatedly scrawl the titular phrase on the walls of a gallery. Baldessari himself was not present as the students did so, and the work, which looks like the result of a schoolmaster’s punishment, became a way of testing notions about authorship. The artist had removed his hand from the work, and yet, by some strange logic, Baldessari could still be said to be the creator.

This work and others like it did not resemble the Abstract Expressionist works that had become so popular a little more than a decade earlier by foregrounding formal exuberance and privileging artistic genius. The way in which Baldessari’s works were made and their look now mattered little.

Because of his interest in ideas, many critics have lumped in Baldessari with a group known as the Conceptualists, who also made use of Duchamp-inspired hijinks to toy with people’s expectations of art. Joseph Kosuth created a sculptural piece about the word “chair”—rendered as an object, a definition, and a photograph—in search of the term’s various meanings, and Lawrence Weiner left instructions for the removal of a section of a floor as an artwork. Objects were being dematerialized, authorship was starting to mean very little, and the very aesthetic of an artwork was becoming slippery and amorphous.

But because Baldessari was based in California and not New York, where many of the other Conceptualists worked, he was considered an outsider—an artist who could not take his work seriously enough to matter. Kosuth, for one, famously dismissed Baldessari’s art as “‘conceptual’ cartoons.” Yet Baldessari kept abreast of what was taking place halfway across the world, and in 1972, for a video called Baldessari Sings LeWitt, he intoned pieces of artist Sol LeWitt’s “Sentences on Conceptual Art” to the tune of the “Star Spangled Banner” and other popular ditties. Baldessari once told New Yorker critic Calvin Tomkins, “The Conceptualists thought I was just doing joke art, and I thought theirs was boring.”

Leading abstract artists of the day also tore into the kind of work Baldessari and Californian colleagues such as Ed Ruscha were making. Baldessari once heard that the painter Al Held had said conceptual art was “just pointing at things,” and so Baldessari thought to literalize that. For the series “Commissioned Paintings,” Baldessari took a photograph of a friend’s hand pointing at things around National City in California, where he was based at the time, and then enlisted 12 amateur artists to pick one of the shots and create their own painting of it.

This was a personal and iconoclastic gesture for Baldessari, who himself began as a painter, crafting bizarre semi-figural works that were based partially on photographs (still a taboo during the early ’60s). Only a few works from his early period remain, however—Baldessari burned all of the work he made between 1953 and 1966 for a conceptual piece called Cremation Project (1970). Among the only remaining works from that period is God Nose (1965), a visual pun on the phrase “God knows” that features a disembodied nose floating in the sky. The reason it exists is because it was in Baldessari’s sister’s possession at the time.

Baldessari was born in 1931 in National City. He studied art history at San Diego State College in California and thought at first that he might want to become a social worker. A studio-art class in 1957 turned him on to the possibility of studying to become an artist, but he realized he may never be able to square his social consciousness with an art career and demurred. Then, while working at the California Youth Authority, he was asked to start an arts-and-crafts program, and he changed his mind. Several years after studying at the hallowed Otis Art Institute in Los Angeles, he saw a landmark 1963 retrospective for Marcel Duchamp at the Pasadena Art Museum that was curated by Walter Hopps, and that sent him down a less traditional route.

At the same time that Baldessari was shaking up the California art world, he was on his way to becoming one of the most important educators in the history of American art. Baldessari was among the first to teach at the California Institute of the Arts (known as CalArts for short), a school in Santa Clarita that quickly became a hotbed for radical art-making during the 1970s. Baldessari was asked to teach a painting class—which he quickly decided against, instead opting to oversee a course called “Post-Studio Art.” (What, exactly, was meant by its name was deliberately broad and somewhat cryptic.) Among his first students were Salle, Barbara Bloom, James Welling, and Jack Goldstein, all of whom went on to have illustrious careers. He taught at CalArts until 1986, and then at the University of California, Los Angeles until 2008.

The impact of Baldessari’s wide-ranging experiments is impossible to understate—the most important American artists to emerge during the 1980s were looking at Baldessari’s art, viewing it as something that gave them permission to use photographs and text. He helped spur on a movement known as the Pictures Generation, a loose consortium of artists such as Cindy Sherman, Goldstein, and Robert Longo who were viewed the world as being filled with images devoid of value. In the New Yorker profile, Baldessari recalled Sherman once telling him, “We couldn’t have done it without you.”

Not everyone was thrilled with Baldessari’s art, however. The firebrand critic Hilton Kramer, writing on a Baldessari retrospective in 1990, called the Conceptualist movement “an abundance of hot air.” Others admired Baldessari’s penchant for humor—New York Times critic Roberta Smith once wrote that he “makes you look twice and think thrice.”

During the 1980s, Baldessari continued pushing his art in new directions, often by referencing one of the day’s dominant forms of art-making—movies. He began creating works that combine images appropriated from film stills that seem to gesture, albeit vaguely, at surreal narratives combining lust and violence. To these pictures, he later began adding circular swatches of color that obscured faces—which viewers frequently gaze at first when they see a shot in a film. Here again, Baldessari is puckishly reordering how we see, putting a point on secondary elements, such as arms and legs. (Baldessari sometimes attributed his interest in body parts to his own lankiness.) In a short film called A Brief History of John Baldessari that was produced for a Los Angeles County Museum of Art gala in 2009, the artist speculated that he would best be remembered as “the guy who put dots over people’s faces.”

Much of his art in the intervening decades continued in this willfully oddball vein. There was an entire series built around emojis and faux screenplays, and an app that allowed its users to discombobulate and reorder a 17th-century Dutch still life painting. There were an installation involving a 625-pound relief of a human brain and some surprising forays into painting.

In the later decades of his career, he began to achieve market success, too—he got representation with Marian Goodman Gallery, which is among the most esteemed enterprises with an international presence, and his works finally began selling for millions at auction. This was coupled with a traveling retrospective in 2009 that started at Tate Modern in London and also went to the Museu d’Arte Contemporani di Barcelona, LACMA, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. (It was one of the most momentous Baldessari shows since a survey that opened in 1990 at the Museum of Contemporary Art Los Angeles.) He also received the Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement at the Venice Biennale in 2009.

Baldessari was frequently asked where he got his ideas, and he often cited art history itself. He was an admirer of art from all periods of art history, and he even named his dogs Goya and Giotto. In a New York Times interview from 2016, he fantasized about an alternate life in which he became a historian who could be called Dr. Baldessari, adding, “I do believe that art comes from art.”

[ad_2]

Source link