[ad_1]

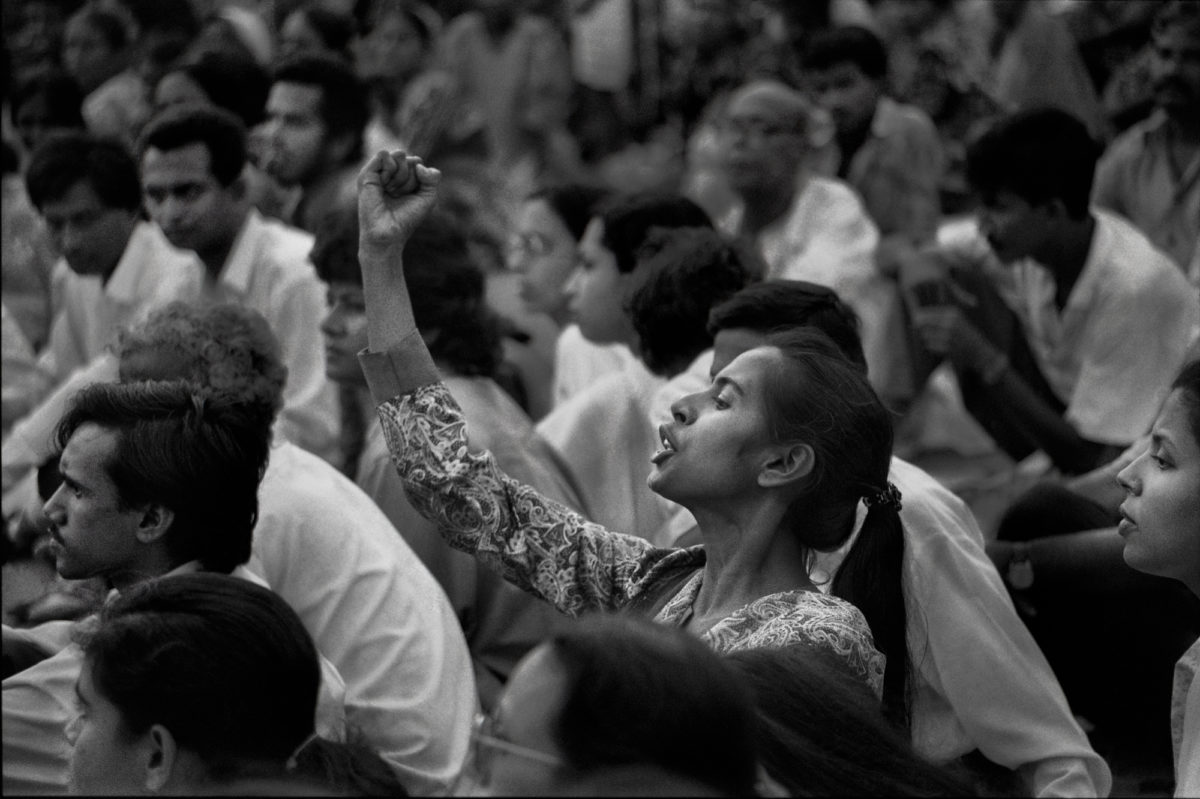

Shahidul Alam, Smriti Azad at Protest at Shaheed Minar, Shaheed Minar, Dhaka, Bangladesh, 1994.

“Smriti Azad used to attend political rallies with her sister when she was a child. As a singer and a performer, she was involved with the women’s movement, the committee demanding the trial of war criminals and the cultural group Charon Shangshkritik Kenro, which led to her joining the cultural group Shommilito Shangshkritik Jote. As part of that group she was active in the movement to bring down general Ershad. Here, Smriti was protesting at a rally at Shahid Minar.”

COURTESY THE ARTIST/DRIK/MAJORITY WORLD

Though he’s an accomplished photographer, Shahidul Alam may be best known for something other than taking pictures. In 2018, Alam spent over 100 days in jail after speaking out in defense of student protestors in his home country, Bangladesh. His bold advocacy for free speech earned him an unusual accolade for artists: the title of Time magazine’s Person of the Year.

Now New Yorkers will have a chance to see his art. On November 8, the Rubin Museum of Art will open the first comprehensive U.S. survey of Alam, who has spent four decades using photography as a tool to protest social injustice—a project with which he’s been engaged ever since the 1980s, when he campaigned to bring down the autocratic regime of General Hussain Muhammad Ershad. In addition to taking photographs that have wound up in museums and publications across the world, he established the Pathshala South Asian Media Institute, the first school of photography in South Asia, and in 2000, he founded Chobi Mela, an international festival for photography. He also co-established the international photo agency Majority World. He has won the Lucie Foundation Award, the Frontline Club Tribute Award, the ICP Infinity Award, as well as the Shilpakala Award, the highest cultural award given to Bangladeshi artists.

Last month, while in New York to assist with preparations with his exhibition, Alam sat down with ARTnews to discuss his career. A friendly, inquisitive, and humble man, he is constantly thinking through political issues—especially when speaking about his own images. His Rubin exhibition will have 40 pictures spanning his career that reflect the political state of Bangladesh. And it will also feature what Alam could not photograph: the inside of the prison in which he was jailed and tortured, which he is presenting in the show as a sculptural model. Though only released on bail due to an international outcry on his behalf, Alam still faces 14 years in prison. He seemed optimistic about his future during the course of this interview, however.

ARTnews: When you first started taking photographs, what inspired you to use them for social justice?

Shahidul Alam: It was actually the other way around. Because I saw what photography could do, I chose to become a photographer. I was then doing my Ph.D. in London. I was involved with the Socialist Worker’s Party and in activism around AIDS and gay rights and a whole range of issues of that sort, and I looked around to see what photography could do for those issues. I was training as a research chemist, and I asked myself whether Bangladesh needed another research chemist. The actual taking up of the camera was somewhat accidental, but the decision to do it came largely through the activism.

How did you get into activism?

I have never known a time when social justice was not a part of me. Given that I’m from Bangladesh, given that we went through a war of liberation, and given that we went through genocide, I’m sure it was something that had a lasting effect on me. I have seen what people could do to people, and I always knew that was wrong. And I have always felt that I had a role to play in ensuring that it never happens again.

Is this what you teach photographers about at the institutes you’ve set up?

Not just photographers, and I will repeat that. I think I am a photographer and I am writer, but I actually do not see that as my primary role. I am someone who is committed to social reform and to social justice, and I use photography because it works.

Yet you are having a photography exhibition.

If I am fighting a war to win, I will choose the best weapons.

Shahidul Alam, Rohingya Refugees After Having Just Landed in Bangladesh, Shah Porir Dweep, Teknaf, Bangladesh, 2017.

“Rohingya refugees from Myanmar rest after landing in Shah Porir Dweep in Bangladesh on the night of October 5, 2017. Having just arrived, this family has no idea where to go next. They are relieved to be alive. The following morning they went to Teknaf. The extreme violence that Buddhists have demonstrated in Thailand, Sri Lanka, and Myanmar is not limited to Buddhism alone. The violence by Muslims, Christians, Hindus, and Jews—all in the name of religion—is the bane of our world today. Being the “wrong” religion, color, race, class, or sex is the reason why entire populations have been decimated, unjust wars waged, and innocent people brutally persecuted across the globe. The photographs of Rohingya refugees fleeing persecution in Myanmar show their visible pain. The torment, the insecurity, the fear, the burning inside, the sense of eternal loss remain undocumented.”

COURTESY THE ARTIST/DRIK/MAJORITY WORLD

What does this exhibition mean to you, then?

This exhibition follows the trajectory of what has happened [to me]—and also a phenomenal movement that is taking place in a country like Bangladesh, which, in a relatively short time, has become such a major part of the photographic world. The school of photography is known to be one of the finest in the world, and many great photographers are coming out of Bangladesh. And while Bangladesh is known for many things, this is not an aspect that the general public knows about, and I think it is worthwhile to remind people of that. But I also think it is a question of the Bangladeshi story in a broader sense. Countries like Bangladesh are reduced to very simplistic terms. They become clichés and stereotypes, and through this work, people will get a much richer, more nuanced understanding.

One component of the show is a model of the jail. Photography is very good at recording what is in front of your eyes. It’s not as good at reporting what isn’t. A lot of my recent work has been about that. In 2010, I made work about extrajudicial killings, and since then, I have done a trilogy of exhibitions on the disappearance of an indigenous woman activist, Kalpana Chakma. I’ve been trying to find new vocabularies to tell these stories. But more recently, when I was in jail, the camera itself was missing, and for me, the challenge has been: How does a photographer tell the story when the camera itself is missing?

Can you talk about what it was like getting arrested last year?

In August, I was talking to the BBC on the phone about a story that I would do the following day when the doorbell rang. I opened the door, and that’s when all these people came out from the back. Pretty soon, I worked out what was going on. At that time the most important thing was to make sure that others knew this was happening, because had I gone away quietly and had people found out an hour or two later, it probably would have been too late. So I resisted. I screamed. I attempted to create as much noise, in whatever way [possible], so my disappearance would not go unnoticed. When they were torturing me, they were talking about my worse treatment to come and that my family would be picked up as well, and I had to make a decision not just for me but for my family and the people around me.

And what was that decision?

To not give in. And later on, when a deal was made that I could be let free and it would all be deleted with nothing on the record, provided I remained silent, I was not prepared to sell my freedom.

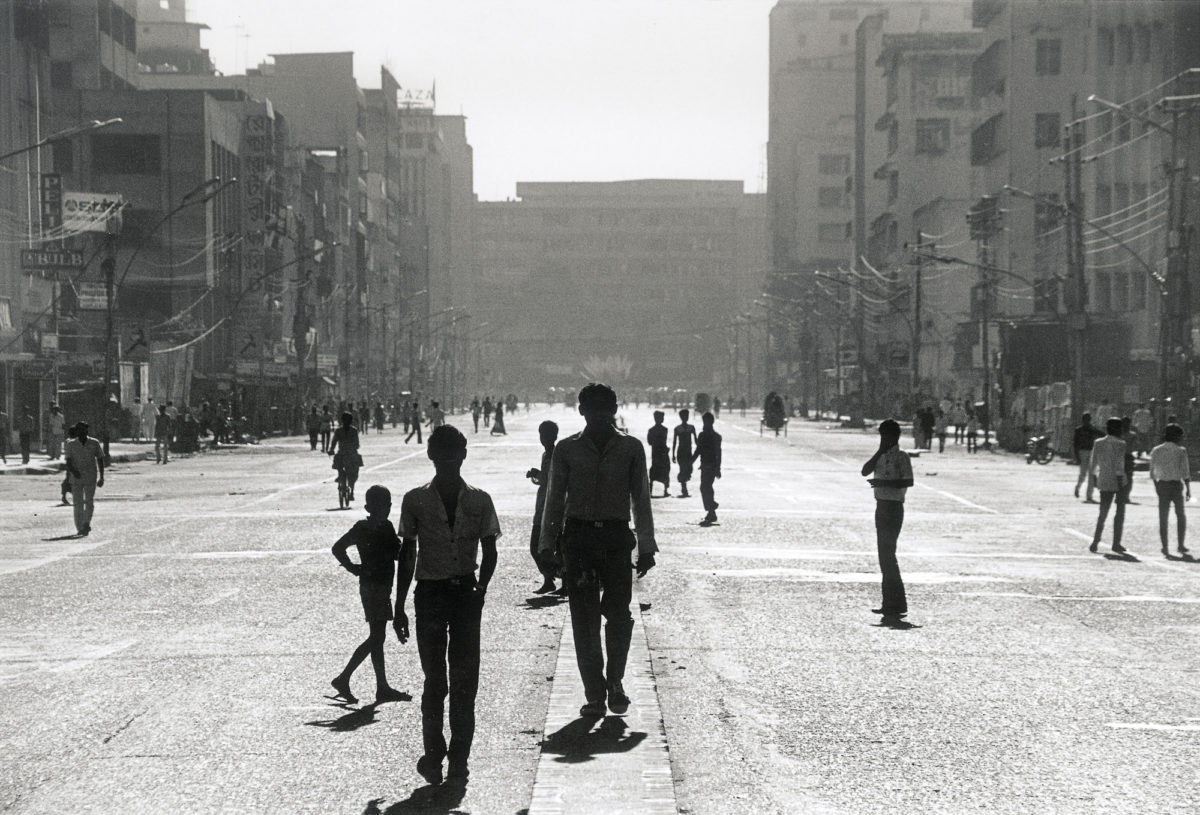

Shahidul Alam, Protesters in Motijheel Break Section 44 on Dhaka Siege Day, Motijheel, Dhaka, Bangladesh, 1987.

“On Dhaka Siege Day, November 10, 1987, the commercial center of Motijheel is empty as opposition parties unite to oust a dictator.”

COURTESY THE ARTIST/DRIK/MAJORITY WORLD

Are you still waiting to go back to court?

The case is still ongoing. But we have questioned the legality of the case, and the court has provided a stay order on the investigation. By December 18, hopefully a decision will be made. I am confident that I will win because there is nothing that I’ve done, and everything I’ve said and done is in the public domain.

And you have a lot of support?

As a photographer and as a writer, I was known in professional circles. Today, ordinary people know me. I just came from Toronto. When I stepped out of the car to go to the hotel, people gathered around me because they recognized me, and at the metro they asked for autographs. People now feel that I stood up for them. It was also true when I was in jail. My fellow prisoners were incredible. They made sure that nothing would happen and took care of me in so many ways. Generally, nothing happens in jail without money, but the one person who made the mistake of asking me for money was transferred by the prisoners. “You do not ask this guy for money. We will take care of him.” I did interviews everyday. I researched. I wrote. We set up a musical band. We developed a library. We painted over 35 murals, one of which is based on a photograph of mine. We talked about what they might do and we thought, Why not make pictures of our own lives? So there are pictures of prisoners going about their daily lives.

How did you get the prison’s permission for all of this?

I mean, I was just one of the people within a group of prisoners who asked the warden for permission. And we were perfectly happy for the warden to get credit. As long as we got the work done, we didn’t care who took the [credit].

You have done a lot to open schools and institutions to encourage more people in Bangladesh to become photographers.

To become responsible citizens who can also take photographs.

What do you think you and other Bangladeshi photographers bring to the process of documenting Bangladesh that others can’t bring?

There are two aspects to this. First, there is a power relationship. Someone with a camera has power over the person who is being photographed. That is amplified when that person is a white western photographer from New York or wherever and it’s a farmer in the field. But even when I am taking pictures as a male middle-class photographer, I happen to be in a position of power. That is one distance I have tried to overcome. We have trained women photographers, and we have trained working-class children to make [the medium] more participatory.

This allows people who have a better understanding of the culture, who have more in-depth knowledge and are accountable to their community, to become the story tellers. It changes the equation to a large extent. But I think we have to go further than that. Often photography is done because of things that have been highlighted in the media. It happens after the event. I think local photographers smell the event before it happens. They know about things that are happening that are subtle, complex, told in much more nuanced way.

Shahidul Alam, Airport Goodbye, Dhaka Airport, Bangladesh, 1996.

“At Dhaka International Airport, only passengers were allowed into the terminal building. It was difficult to hear across the glass wall, except through the gap at the hinge, so people took turns speaking. One would speak, and the other would turn their head to listen. Here, a woman bids goodbye to her man, unsure of when they might meet again.”

COURTESY THE ARTIST/DRIK/MAJORITY WORLD

Is there one photograph in the exhibition that functions for you that way?

Airport Goodbye [an intimate picture of a man who is a migrant worker and his wife talking, perhaps for the last time, through a crack in a glass wall separating visitors from passengers at the airport]. Migrants are seen as people fleeing situations or wanting economic development. But for many migrants, [moving] is the only way that they can change their destiny. We all aspire to things. When you are better off, this is interpreted as drive or ambition. When a migrant does it, it is interpreted in a very different way. Here, the passengers, the migrants, are allowed to go into the main terminal of the airport but their families are not. Because the walls are made of glass, they can’t hear each other except for this crack in a doorway where a husband and wife are taking turns speaking to each other. This is a woman saying goodbye to her man whom she might never see again. Going to an unknown future in a situation he had no control over.

How did you know to take that picture? You are so close to them, but they don’t seem to notice you.

That is what photography is about. Camera manufacturers tell you that you need to get a certain camera and you need to get a certain lens. But photography is much more about human relations. It’s about not being intrusive. It’s about recognizing the dignity of others. Provided that you are respectful to people, they will respond in a great way.

Are you working on anything now?

I’m doing a story about with portraits of survivors of torture. One picture I took is of young man who was shot in the leg—his leg had to be amputated. A 16-year-old boy who loved sports and lost a leg for no reason other than security forces running rampant. I’ve developed a particular lighting situation. I ask people to remember that moment [when they were tortured], and I record the expressions that come to their mind. You are photographing an emotion instead of a face. People have opened up their hearts and given me unprecedented access.

Are you going to take any time to celebrate your Rubin show?

I think we will be celebrating, because we all should be celebrating the power of the people.

[ad_2]

Source link