[ad_1]

Titled “Coronavirus Disease Outbreak in Call Center, South Korea,” it describes how South Korea dealt with an outbreak in a high-rise building in the busiest part of Seoul with an early, decisive intervention that included closing the entire building, extensive testing and quarantine of infected people and their contacts. The study was conducted by experts from the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the Seoul Metropolitan Government and other local institutions.

Though a one-building solution, the authors’ approach to identification and control of Covid-19 can serve as a blueprint for local and national policymakers wrestling with how best to proceed.

Informed by previous outbreaks of SARS and MERS, South Korean health officials had a mature process for containment already in place when the first call center case was identified. A response team immediately undertook review of the site of the infections — a 19-story mixed commercial-residential building.

On March 9, one day after the first cases were reported, the entire building was closed. Testing was performed almost immediately on 1,143 people (workers, residents and a few visitors) with rapid results available to those affected and the team working to control the situation.

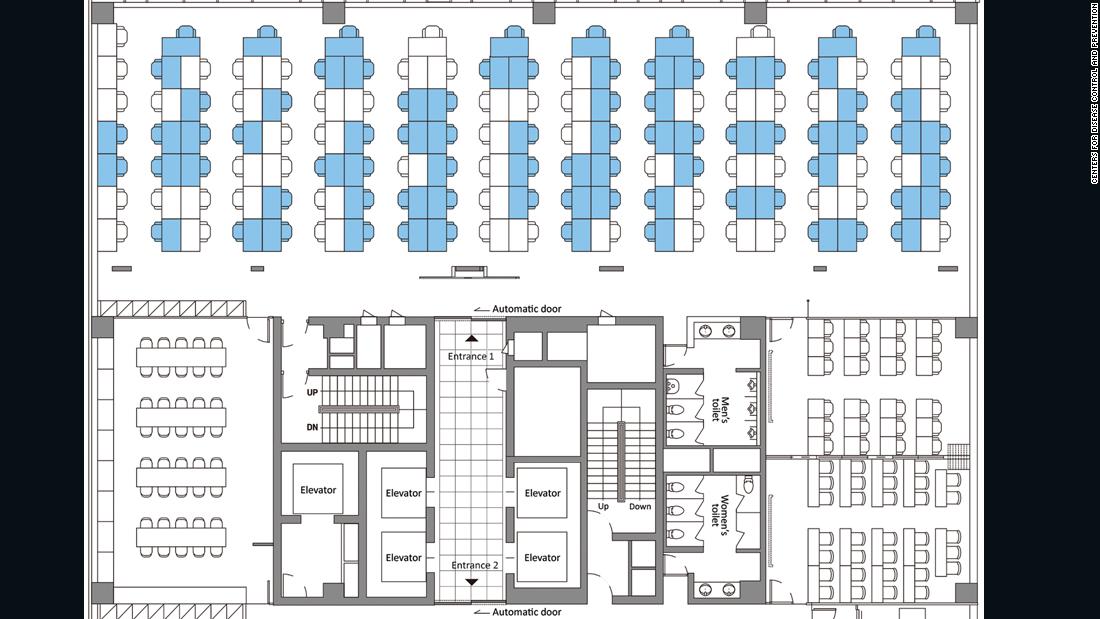

The testing showed that 97 people (8.5% of those occupying the building) were infected. Most of the cases were women in their 30s and almost all (94 of the 97) worked on the 11th floor of the building, in the call center.

Curiously, unlike many outbreaks reported before and since, virtually all of those infected — 92% of cases — had active Covid-19 symptoms at the time of diagnosis.

Next, the South Korean team tested the families and housemates of the 97 people with infection. Of these, about 16% were positive for Covid-19. Very surprisingly, no cases were diagnosed in the 15 home contacts of cases with “pre-symptoms” (nothing at time of test but development soon thereafter) or no symptoms at any time. This also goes against the current thinking on transmission, which is that it occurs even before people show symptoms.

In their discussion, the South Korean investigators reflected on the effect their work could have for business-as-usual in Seoul. They point out that the cases were in a “high-density work environment” and that spread was largely limited to one section of one floor.

But they fail to give themselves credit for what they accomplished. Yes, the distance between chairs and the duration of exposure are critical determinants of transmission at a single point in time — but allowing undiagnosed persons to unwittingly go about their business increases the opportunity for more and more uninfected people to have close and sustained contact with them, possibly leading to a secondary case.

Had the investigators waited a week, the infection would likely have spread widely to family, then to friends, then to friends’ workplaces — just as we are seeing in the outbreaks in US meat processing plants with a comparably high-density work environment. The virus knows no walls: Once a business is infected, the entire community may quickly become infected, unless dramatic action — such as occurred in Seoul — is taken.

The current notion of some American public officials of simply reopening our cities and towns — like a department store grand opening that goes from nothing to a complete full-service store overnight — surely is a pipe-dream. But this report from South Korea shows us how we actually can handle the uncertain business of resuming a normal-ish life.

To do so will require decisiveness such as quickly closing an entire building if needed, widely available testing with rapid results, and citizens willing to be quarantined as needed for the public good.

Only by adopting this blueprint in its entirety can the vision of returning to a vibrant free-swinging nation be achieved. Trying to sneak back by ignoring the problem — a pandemic that has killed more than 60,000 Americans in two months — or by hoping that maybe it will go away if we eat this or drink that or don’t spend so much time worrying — will not only fail miserably, it will move us immediately back to the terrifying first weeks of March, when the sky actually felt like it was falling.

[ad_2]

Source link