[ad_1]

*This post is part of our roundtable on Keri Leigh Merritt’s Masterless Men.

Ta-Nehisi Coates and members of his fan club must read Keri Leigh Merritt’s deeply-researched, well-reasoned, and eye-opening book, Masterless Men: Poor Whites and Slavery in the Antebellum South (2017). They should read it, above all, because it convincingly challenges several of Coates’s insufficiently-supported and profoundly-wrongheaded statements, including this one: working-class whites, not elites, “have historically been the agents and beneficiaries of” racism. Indeed, it is extremely hard to take this claim seriously after reading Masterless Men, a book that outlines the many difficulties and dramatic struggles of both slaves and poor whites under oppressive conditions—conditions established by agricultural elites and vociferously defended by their political allies. Thankfully, Merritt has challenged an all-too-common view in our post-New Left historiographical climate: the idea that class, as a category of analysis, somehow lacks explanatory power, is simply too old-fashioned, or that its defenders are narrow-minded and naïve leftists.

As Merritt demonstrates in nine tightly-argued chapters—that provide readers with extensive descriptions of class and race conflicts—Coates’s statement about working-class whites could not be further from the truth. In the process, Merritt calls into question some of the most influential and time-honored interpretations of southern slave societies. After reading her book, it is difficult to see how impoverished whites, forced to reside in squalor and periodically harassed and bullied by landowners and slave patrols, somehow benefited from what groundbreaking historians W. E. B. Du Bois and Theodore W. Allen have famously called the “psychological wage” of whiteness and “white skin privilege,” respectively. This is not a book about Black, white, or southern identities; rather, it is principally about power and resistance.

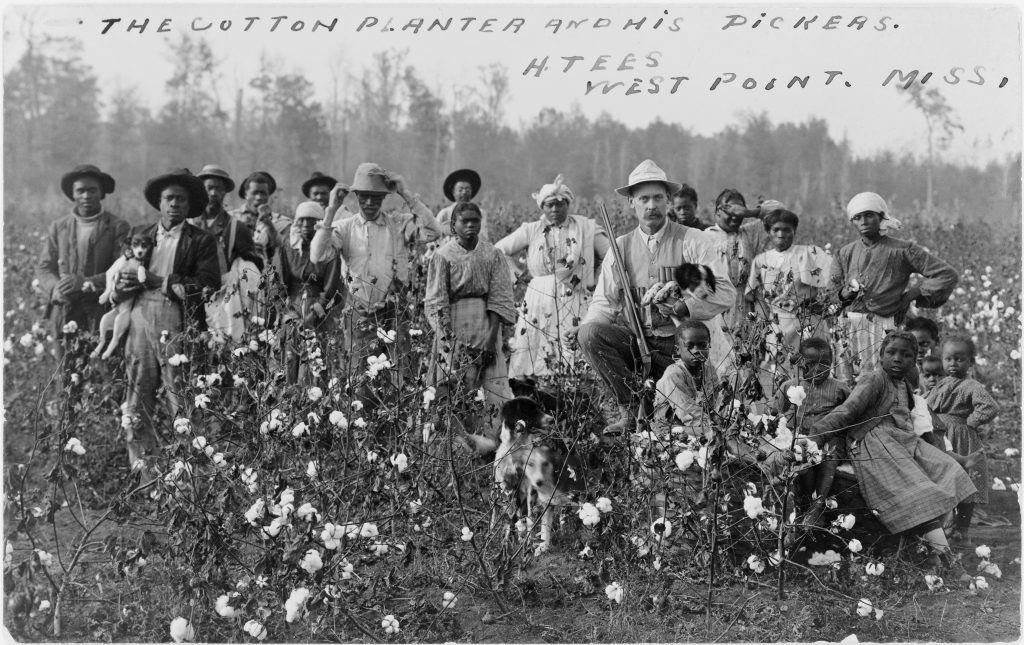

Merritt does a fantastic job recounting the day-to-day struggles of the African American and poor white masses. Her analysis of ordinary whites—vivid accounts of anxiety and misery rather than of comfort and privilege—is especially thoughtful and provocative. Their severe poverty meant inadequate diets, poor housing conditions, lack of educational opportunities, and a greater exposure to illnesses. Yet they were not merely victims, and Merritt mentions that many poor whites, both during periods of work and leisure, developed relationships across racial lines. “Whether in the fields or in the factory,” Merritt writes, “poor white workers had long noticed the fading distinctions between them and their enslaved co-laborers” (72). We learn that there was a considerable amount of fluidity in these communities, and both poor whites and slaves took part in various social and lawbreaking activities, including exchanging goods in the underground economy.

The mostly agricultural-based southern ruling-class repeatedly expressed profound annoyance by the different examples of interracial cooperation. And Merritt’s analysis of what Elizabeth Esch and David Roediger have called “race management” is as insightful and important as her rich descriptions of the social lives of slaves and poor whites. We learn that “so many slaveholders became preoccupied with segregating the two groups” (67). Indeed maintaining a racially divided working-class and preventing anti-slavery ideas from circulating involved considerable amounts of planning over the course of decades. This ruling-class could not simply assume that poor whites would always think and behave in racist ways; masters felt the need to strategize and encourage expressions of white supremacy, which in practice meant banning abolitionist literature and punishing advocates of such ideas.

But members of the slave-owning class and their allies, Merritt explains, remained highly anxious, habitually afraid of losing control. Take the case of Alfred Iverson, the senator from Georgia. He responded to the publication of Hinton Helper’s anti-slavery book by demanding that plantation owners “hang every man who has approved or endorsed” it (274). This is a remarkable statement, illustrating sheer bloodthirstiness. Iverson obviously had no tolerance for dissent, demanding that all whites, irrespective of class, support the exploitative system. He articulated a view that was commonplace in elite circles, and Merritt’s bluntness on the matter is refreshing: “there was simply no freedom of speech in the slave South” (274).

Merritt demonstrates that well into the Civil War period, ruling elites, unable to achieve peace-of-mind, continued to struggle to preserve their power over the interracial working classes. In the face of major political changes, the ruling elites employed fear, insisting that wages for ordinary whites would decline, whites and Blacks would become social equals, and racial conflict would worsen. Merritt points out that Georgia Governor Joseph Brown continued to use classic divide-and-rule messages in 1860, when slave owners felt the bitter sting of an anti-slavery movement that had begun to enter the political mainstream. Brown worried about the possible development of a post-slave society, but was prepared to use racism to maintain control, which he explained in an appeal to ordinary whites: “The black men who lives [sic] on my land has [sic] as strong an arm, and as heavy muscles as you have, and can do as much labor. He works for me at that rate, you must work for the same price, or I cannot employ you” (291). This statement reminds us that for those at the top of society, racism served class interests, and that elites remained committed to employing race management with or without slavery.

Neither persuasion nor fear-mongering was enough to convince all poor whites to fully embrace white supremacy. For this reason, slave owners and their agents frequently turned to brutal methods, and Merritt offers graphic details of the different forms of elite-generated intimidation and violence: kidnappings, whippings, raping, and killings of both Blacks and whites. Such actions were reinforced by public policies, including vagrancy laws. Terror pervaded southern society: “masters needed a terroristic system of policing, surveilling, and torturing the poor (both white and black) to preserve their cherished institution” (253). This is brilliantly stated and captures the nature of the cruel class relationships. The takeaway from Merritt’s research is clear enough: racial similarities across class lines—a shared whiteness—could not guarantee harmony for the region’s rulers.

Merritt observes that we can draw meaningful connections between the Antebellum’s political-economy of racism and violence to developments in more recent times (291). The ruling-classes and their supporters continued to promote racism in the face of organizing efforts by Blacks and whites following the Civil War. Ensuring that ordinary whites remained racially conscious was challenging. We know that the first Ku Klux Klan, typically led by white elites, routinely brutalized former slaves and their white allies. And in the mid-1880s, from Richmond, Virginia to Thibodaux, Louisiana, elite men, organized in various “law-and-order leagues,” violently fought the Knights of Labor (KOL), which had enjoyed some successes in bringing Black and white workers together on class lines.

There is no reason to stop this analysis in the 1880s. We can spotlight similar organizing actions designed to spread white supremacy in the late nineteenth- and early-twentieth centuries, including the 1898 Wilmington coup, a vicious, elite-led campaign that broke up the interracial city council and led to the deaths of roughly thirty African Americans and to the expulsion of more than 2,000. Or take the activities of the second Klan during the World War I era, when its members helped employers break strikes, including those led by African American longshoremen. And in the 1930s and 1940s, promoters of anti-union right-to-work laws were the most aggressive defenders of Jim Crow policies. Vance Muse, the Texas-based leader of a business-funded Astroturf organization, the Christian Americans, frequently warned white workers to avoid the racially-inclusive Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO): “from now on, white women and white men will be forced into organizations with black African apes whom they will have to call ‘brother’ or lose their jobs.”

We can identify a common pattern. In all of these cases, ruling-class whites, some of whom collaborated with Black elites, have historically devoted considerable amounts of energy on developing quiescent workforces, community stability, wealth, and power. The political-economy of racism, told authoritatively by scholars such as Merritt, had as much to do with exploitation as it did with what today’s mainstream Civil Rights organizations like to call “hate.” Not all racists were violent haters. Plantation and factory owners did not seek to injure, kill, or otherwise punish their productive and obedient Black workers.

The same cannot be said about their responses to rebellious laborers or “outside” agitators of any race, including abolitionists in the antebellum period, Union soldiers during the Civil War, Republican educators during Reconstruction, KOL activists in the 1880s, Industrial Workers of the World members in the Progressive Era, and CIO organizers in the 1930s. Examples of elite forms of racist oppression are important to illustrate—and to illustrate forcefully—at a time when millionaire essayists such as Coates are guilty of richsplaining to us in bourgeois publications, erroneously insisting that working-class whites have historically been the chief “agents and beneficiaries” of white supremacy. Fortunately, careful historians such as Merritt have helped to set the record straight.

Copyright © AAIHS. May not be reprinted without permission.

[ad_2]

Source link