Adventures with Van Gogh is a weekly blog by Martin Bailey, our long-standing correspondent and expert on the artist. Published every Friday, his stories range from newsy items about this most intriguing artist to scholarly pieces based on his own meticulous investigations and discoveries. © Martin Bailey

The first-ever exhibition on Van Gogh’s period in Auvers-sur-Oise has opened in Paris, at the Musée d’Orsay. During the summer it was presented at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, attracting 583,000 visitors. Even more are expected in Paris, so it will get well over 1m in the two venues, putting it among the world’s most popular shows of the year.

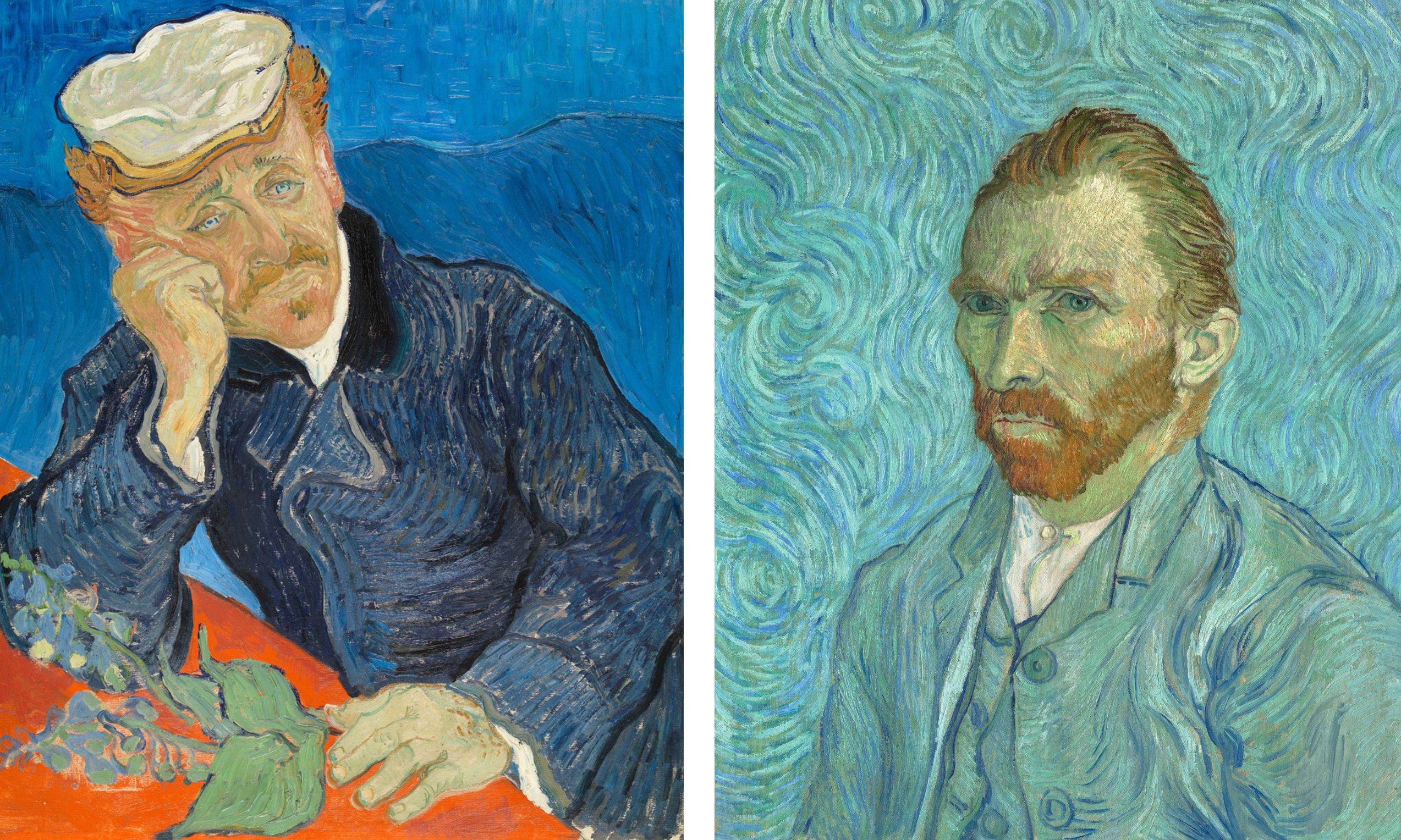

Van Gogh’s Dr Paul Gachet (June 1890) and the Self-portrait (September 1889) given to Dr Gachet

Credits: Musée d’Orsay, Paris (RMN Grand Palais/Patrice Schmidt)

Van Gogh in Auvers-sur-Oise: The Final Months (until 4 February 2024) includes 47 of the 74 surviving paintings he completed in the village, which lies 30 kilometres north west of Paris. Arriving on 20 May 1890 from the asylum in Provence, he lived in Auvers for 70 days, completing a picture a day in an extraordinary burst of energy. It is very unlikely that any future exhibition will have such a comprehensive collection of the Auvers paintings.

Just before the opening of Van Gogh in Auvers-sur-Oise: The Final Months, Musée d’Orsay, Paris

Credit: The Art Newspaper

The Musée d’Orsay exhibition curator Emmanuel Coquery has even succeeded in reassembling 11 of the 13 large “double-square” paintings which Van Gogh made during the last four weeks of his life, before his death on 29 July 1890. These panoramic works have come from collections in Amsterdam, Basel, Cardiff, Cincinnati, Dallas, London and Vienna (the missing two are one in Hiroshima and another in Basel). They include his very last picture—the astonishingly bold Tree Roots (Van Gogh Museum, July 1890), painted on the very day that he shot himself.

Van Gogh’s Tree Roots (July 1890)

Credit: Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation)

The majority of the “double squares” depict the vast wheatfields on the plateau above the village, devoid of people, some under threatening skies. Seeing them in the Musée d’Orsay show, one feels the sense of isolation that Vincent suffered – and which helps to explain the fateful decision to end his life.

On 10 July 1890, a fortnight or so before he picked up the gun, Vincent wrote to his brother Theo that he had depicted “immense stretches of wheatfields under turbulent skies, and I made a point of trying to express sadness, extreme loneliness”.

Much new research has gone into the Amsterdam-Paris show. Among the surprises is the discovery of some very early frames for Van Gogh works. These were commissioned by Dr Paul Gachet, the artist’s closest friend in Auvers, and one has a label on the reverse showing that it was on a painting in a 1905 exhibition. It is likely that the frames with slightly bevelled edges date from 1890 and it is even possible that they were made to the design of Van Gogh himself, who favoured simple wooden surrounds over ornate gilded ones. In 1905 Gachet’s son wrote that their frames were the bevelled ones used by Van Gogh.

The Gachet frames were inherited by the doctor’s son, who in around 1950 gave them to a neighbour, Florent Giordano, whose son donated them to Dominique-Charles Janssens, the owner of the inn where Van Gogh had died. Janssens has now lent one of the frames to the Musée d’Orsay exhibition and replicas were then made for four of the Van Goghs which had once been owned by Dr Gachet.

Van Gogh’s Thatched Cottages in Cordeville, Auvers-sur-Oise (May-June 1890) in a replica of the early Gachet frame

Credit: Musée d’Orsay, Paris (RMN Grand Palais/Patrice Schmidt; (Photograph: The Art Newspaper)

It is revealing to compare the Gachet frame with the ornate one which the Musée d’Orsay had used on Thatched Cottages in Cordeville, Auvers-sur-Oise (May-June 1890) until the current exhibition. The ornate frame is distracting and appears to constrict the painting. The simple wooden frame allows the painting to “breathe”, making the landscape seem more open.

Two ways to present a Van Gogh: The Musée d’Orsay’s ornate frame and the its new replica Gachet frame for Thatched Cottages in Cordeville, Auvers-sur-Oise (May-June 1890)

Credit: Musée d’Orsay, Paris (RMN Grand Palais/Patrice Schmidt) (photograph: The Art Newspaper)

For those going to the Paris exhibition, I would thoroughly recommend a day trip to Auvers (about one hour by train), the "village of artists”. Before Van Gogh’s arrival, it was once home to the slightly earlier landscape painters Charles-François Daubigny, Camille Pissarro and Paul Cezanne. Afterwards numerous later artists followed in Van Gogh’s footsteps.

The most moving site in Auvers is the inn where Van Gogh lodged, the Auberge Ravoux, where one can visit the modest bedroom where he slept—and died. The room is left empty, except for a simple chair. For Van Gogh, empty chairs symbolised the departed. Small numbers of visitors are allowed into the room on tours. Janssens, who acquired the inn in 1987, describes his visitors as “not really tourists, but pilgrims”.

Auberge Ravoux, Auvers

Credit: Chabe01 via Wikimedia Commons

Five minutes’ walk away is the church, the subject of one of Van Gogh’s finest Auvers paintings. And five minutes further on is the cemetery, where Vincent is buried next to his dear brother Theo. Their twin graves are covered with a blanket of ivy, one of Vincent’s favourite plants.

Van Gogh’s Church at Auvers (June 1890) in its replica Gachet frame

Credit: Musée d’Orsay, Paris (RMN Grand Palais/Patrice Schmidt) (photograph: The Art Newspaper)

There are also three other key sites in Auvers. The Maison Gachet, the house of Van Gogh’s friend, reopens this weekend, with an entirely fresh redisplay. Gachet was a fascinating character – a doctor, collector and amateur artist – and a visit to his home tells the story of his extraordinary life.

Maison Gachet, Auvers

Credit: The Art Newspaper

Between the Maison Gachet and the Auberge Ravoux lies the Château d’Auvers, an imposing 1635 mansion which since 1994 had housed a multi-media presentation on the Impressionists. It has now been reconfigured to focus purely on Van Gogh. For true art lovers, Van Gogh: the last Journeys also includes some original paintings—not by Van Gogh, but mostly modest works by artists whom he admired or who depicted Auvers scenes. It too reopens this weekend after a refurbishment. Both the Maison Gachet and the Château presentations have been overseen by the Van Gogh specialist Wouter van der Veen.

And finally, there is a new attraction: the actual roots and stumps which feature in Van Gogh’s painting Tree Roots. In 2020 Van der Veen was astonished to find a postcard of around 1910 which appeared to show the same roots as in the painting. On visiting the spot, he realised that these very same roots survive. Vegetation has been cleared away and the roots are now protected by fencing. The roots can be viewed from the street in Rue Daubigny, near number 46, and tours just inside the property are now organised.

Visiting Auvers, it is easy to understand why it attracted Van Gogh and his fellow artists. The atmosphere on the “vieille Route” (old road, now renamed Rue Daubigny) and in the fields on the plateau just above the village remain very much as they were in 1890, although the old thatched cottages have long gone.

It is revealing to compare Van Gogh’s landscape paintings in the Musée d’Orsay exhibition with the picturesque countryside around Auvers. A few places where he worked can be seen today (such as Church at Auvers and Tree Roots), while other paintings so brilliantly capture the atmosphere.

Van Gogh always preferred to work outside, in front of the motif which inspired him. But in Auvers he never slavishly depicted a scene. Using artistic licence, he allowed his imagination free rein to create his masterpieces.

• For more on the story of the artist’s last months, see my book Van Gogh’s Finale: Auvers and the Artist’s Rise to Fame.

Other Van Gogh news:

London’s National Gallery will be holding a major exhibition next year to celebrate its 200th anniversary: Van Gogh: Poets and Lovers (14 September 2024-19 January 2025). Key loans will include two masterpieces painted in Provence: the Rhône scene Starry Night (October 1888, Musée d’Orsay, Paris) and a version of The Bedroom (September 1889, Art Institute of Chicago).

Martin Bailey is the author of Van Gogh’s Finale: Auvers and the Artist’s Rise to Fame (Frances Lincoln, 2021, available in the UK and US ). He is a leading Van Gogh specialist and investigative reporter for The Art Newspaper. Bailey has curated Van Gogh exhibitions at the Barbican Art Gallery and Compton Verney/National Gallery of Scotland. He was a co-curator of Tate Britain’s The EY Exhibition: Van Gogh and Britain (27 March-11 August 2019).

Martin Bailey’s recent Van Gogh books

Bailey has written a number of other bestselling books, including The Sunflowers Are Mine: The Story of Van Gogh's Masterpiece (Frances Lincoln 2013, available in the UK and US), Studio of the South: Van Gogh in Provence(Frances Lincoln 2016, available in the UK and US), Starry Night: Van Gogh at the Asylum (White Lion Publishing 2018, available in the UK and US) and Van Gogh’s Finale: Auvers and the Artist’s Rise to Fame (Frances Lincoln 2021, available in the UK and US). Bailey's Living with Vincent van Gogh: the Homes and Landscapes that Shaped the Artist (White Lion Publishing 2019, available in the UK and US) provides an overview of the artist’s life. The Illustrated Provence Letters of Van Gogh has been reissued (Batsford 2021, available in the UK and US).

To contact Martin Bailey, please email [email protected]. Please note that he does not undertake authentications.

Read more from Martin's Adventures with Van Gogh blog here.