[ad_1]

Michael Smith, Imagine the view from here! (production still), 1989. Museo Jumex.

COURTESY THE ARTIST AND MUSEO JUMEX, MEXICO CITY

In Mexico City this past winter, I visited numerous shows that dealt with the body and identity. The first was at the Museo Jumex. The museum stands in the middle of a corporate mall complex, in a posh steel-and-glass district of an otherwise very diverse city. What better place for the artist Michael Smith to transform into an office for a fictional time-share retirement community?

Smith’s project took over the museum’s entire first floor—including a terrace that overlooks a corporate plaza. The space felt bare and aseptic, with two marketing stands, one in cool hues carrying English language offerings, the other in red and green, in Spanish. A sign touted various amenities: Wi-Fi, coffee, Uber, limo service, an ATM.

While navigating this space, one was asked to imagine inhabiting the body of a middle-class white male American retiree. Smith played one—his image was visible on a large, wall-mounted monitor that faced museumgoers as they entered the show. In the video, Smith wanders into a sales booth, is offered a flyer, attends one of those cheesy “free” dinners used to sell time-shares, and participates in all sorts of activities in San Miguel de Allende, a colonial town a three-hour drive northwest of Mexico City that, over the past few decades, has been taken over by American retirees. In an art class, in a language class, and at a café, he looks lonely, despite being in the company of others.

At the conclusion of Smith’s video, his retiree arrives at his Mexico City time-share, in the very space where the viewer stands, and is welcomed and assured that his every need will be met. His body has become akin to a logo, micromanaged by a corporate ethic, where views become “vistas,” leisure is planned and surveilled, “culture” can be bought, and death can be postponed.

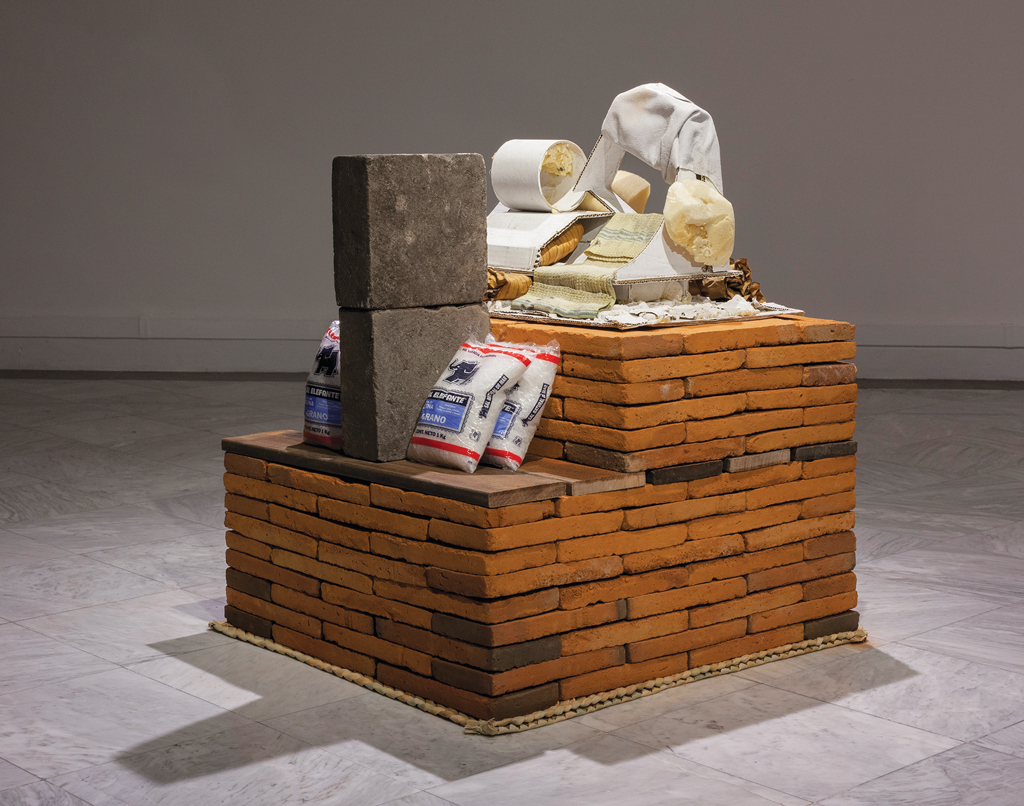

The foil for Smith’s retirement community was the provisional home Theo Michael created for a fictional hermit—a gritty, anti-capitalist escapee, perhaps even a refugee—at (or, rather, under) the Casa del Lago. The titular installation in the exhibition, “The Hermit’s Symmetry,” offered a vision of the hermit’s lodgings: a tent surrounded by a rickety wooden structure that bore above it all the weight of an institution. Inside the tent were the accoutrements of mere survival: canned goods and water, a transistor radio, folding chairs on hand-woven palm mats.

Theo Michael, Interplanetary Farmer, 2018, mixed media, 25⅝ x 29½ x 31½ inches. Casa del Lago.

NATALIA GAIA FOR CASA DEL LAGO, UNAM

An exhibition at BWSMX (Brett W. Schultz, Mexico City), a project by the pop-up gallery Neri | Barranco, grappled with another male stereotype, that of the painter. In Mexico, the traditional image of the painter is that of a hypermasculine “genius” toiling away alone in his studio making a grand ideological statement or, as poet and painter Paloma Contreras Lomas puts it in a curatorial essay for her exhibition of work by Jazael Olguín Zapata, a “revolutionary ejaculation.” Contreras Lomas arranged Olguín Zapata’s paintings such that they undermined that macho sensibility—the works were almost hidden, with some placed in the margins of the gallery.

Olguín Zapata is the author of numerous fanzines, a member of the Cráter Invertido collective, and an active prison abolitionist. He has been called an enfant terrible. His works in this exhibition, titled “Amarres – Descarnes” (Moorings – Discharges), could be read as asking, What happens when that enfant grows up?

The bodies in Olguín Zapata’s work are urban; they negotiate the city constantly and, not unlike Michael’s hermit, they carry a weight: in this case, that of Mexico’s violence, present and past. Olguín Zapata interweaves pre-Hispanic imagery, the legacy of Mexican modernism, and mural iconography even as he questions and retools them. But, in blue oil paintings with titles like Returning to the Preclassic, Still Life and Retrofuture, and Snake Before the Origin of the End (all 2018), pre-Columbian masks, vases, and various symbols remain in the background, almost as pretext or texture.

Whereas Olguín Zapata’s earlier pieces—large-format, layered, and grotesque paintings like In the Skinned Garden (2015–17), in the vein of José Luis Sánchez-Rull or even Germán Venegas—are graphically violent, his more recent works, like the ink drawing Amarres – Descarnes (2018) or Sitting, a Landscape (2015–17), meditate on communication and community, and feature layered cords or ropes or an abundance of blood vessels. Perhaps the mature male artist—the enfant terrible as a grown-up—becomes the kind of community member who creates ties that bind but no longer gag.

Installation view of “Jazael Olguín Zapata: Amarres – Descarnes,” 2018, curated by Paloma Contreras Lomas, presented by Neri | Barranco, at BWSMX.

PJ ROUNTREE/COURTESY THE ARTIST, NERI|BARRANCO AND BWSMX, MEXICO CITY

As it happens, Germán Venegas, whose work has influenced numerous artists, including Olguín Zapata, had his largest survey exhibition in recent years, titled “Everything Else,” at the Museo Tamayo. Here were paintings and sculptures that grounded metaphysics in the physical body.

Venegas deconstructs and questions art history in full awareness of his place in its continuum. In his “Erotic Nudes” series (2005), he both borrows from Velázquez and questions the tradition of the nude by progressively reducing painting to its essence: color, texture. On the lower floor, the exhibition started with a series of paintings titled The Violin and the Flute (2004–08), which obsessively revisits Titian’s Flaying of Marsyas (1570–76); the paintings here evolve from the figurative to the cartoonish to the abstract, as if form itself were being ripped apart.

Venegas’s three-dimensional work is always figurative and tremendously physical; enormous strength and effort is required to carve the sculptures, and the massive results are breathtaking. No dos (2000–02) is a large wooden carving of a half-flayed man that invokes traditional Aztec iconography, as well as the Buddhist art and philosophy at the core of Venegas’s practice. The largest sculpture in the show, a 16-foot-tall Buddha carved from a single piece of wood (Form Is Emptiness and Emptiness Only Form, 2000–02), gave the exhibition structure: on the lower floor, located at the Buddha’s feet, were Venegas’s more “worldly” works, while the upper floor, level with the Buddha’s head, displayed work more philosophically inclined.

By contrast, some of Venegas’s most recent pieces, the ink-and-charcoal drawings on delicate rice paper in his “Tlatoanis” series (2018), are modest in size, and delicate. They bring together his thinking on ego and worldly detachment, and his formal explorations and skillful blends of classical, pre-Hispanic, and Zen Buddhist artistic traditions.

Installation view of “Germán Venegas: Todo lo otro,” 2018–19, at Museo Tamayo.

RAMIRO CHAVES

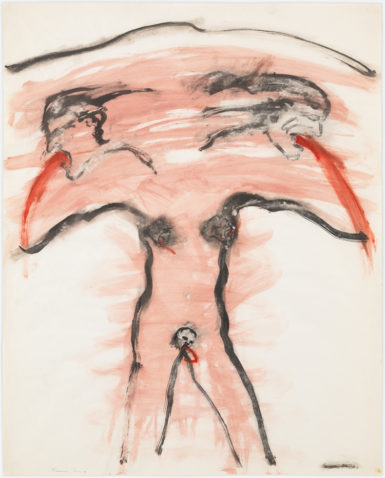

In the galleries across the hall from Venegas’s show was a retrospective of the American painter Nancy Spero, who died in 2009. Spero was not concerned with the metaphysical, but rather the hyperphysical. In drawings she made in the 1960s protesting the Vietnam War, bodies are tortured, their reproductive organs bleeding out (as in Bomb, Tree, Eagle, Lynched Victims, 1967). Spero’s Artaud Paintings (1970), collages with gouache and ink that depict bodiless heads, headless bodies, and thought-provoking sentence fragments, do away with the boundaries between mind and body, madness and sanity, language and the inexpressible in ways that contrast generatively with Venegas’s meditations. Her remixing of traditional and ancient iconographies—where she shares common ground with Venegas—ultimately allows her to slash open the human body, and render it alien. The gender of Spero’s bodies is often unclear. It’s no wonder that her art seems extremely relevant, politically and aesthetically, today.

“La Cabeza Mató a Todos,” a group show at Galería Agustina Ferreyra, continued Spero’s quest to do away with gender binaries. A highlight of the exhibition was a small bronze untitled sculpture from 1975 by the wonderful modernist sculptor Geles Cabrera. The work of Cabrera, one of the few women artists in the male-dominated midcentury Mexican art scene, was recently “unearthed” at a retrospective that artist Pedro Reyes curated at Museo Experimental El Eco. Long before terms like nonbinary were coined, Cabrera celebrated the ungendered, androgynous body. Her bronze figure, arms outstretched, perhaps dancing, doesn’t seem to care how we construe its gender.

Nancy Spero, Female Bomb, 1966, gouache and ink on paper, 34 x 27 inches. Museo Tamayo.

©THE NANCY SPERO AND LEON GOLUB FOUNDATION FOR THE ARTS, LICENSED BY VAGA AT ARTISTS RIGHTS SOCIETY (ARS), NY/COURTESY GALERIE LELONG & CO.

Yet another dancing body is present in La Cabeza Mató a Todos, Beatriz Santiago Muñoz’s 2018 video, which lends the show its title (The Head Killed Everyone). A woman dances while the cat-narrator imagines a society where neither war (traditionally a male activity) nor motherhood (associated with the female) is celebrated and where people are born from eggs or drop from trees like fruit. All these utopian scenarios are offset by the very real yet ambiguous black body of the subject in Dalton Gata’s painting Almost Kitsch (2018), who fiercely smokes a cigarette while crying. This subject, whose body might once have been represented as colonized, objectified, and marginalized, looks straight at us, ready to tell their story.

In Ad Minoliti’s colorful Queer Deco (2018) are more figures that seem content to remain ambiguous. In her digital prints on canvas, Minoliti has placed abstract alien-seeming beings in domestic spaces (images taken from magazines or architecture books). Inhabiting these spaces, the figures are queered—rendered indefinable. Likewise, Madeline Santil’s Úsese hasta agotar existencias (loosely translated as Use until there are no remainders, 2018) transforms purple and lilac dildos into abstract sound objects that vibrate inside canvas boxes.

Back at the Museo Jumex, in an underground gallery beneath Michael Smith’s time-share, was Laureana Toledo’s installation . . . but it often rhymes (2019), consisting of items from London’s Rock & Roll Public Library, a huge and varied archive of pop culture assembled by The Clash lead guitarist Mick Jones.

Toledo spent months picking out objects that speak to colonialism, punk politics, race, class, and gender. Two thousand fanzines, records, and books with titles like Sniffing Glue, Must We Lose Africa? and Anyone here been raped and speak English? were available for scanning and copying by museum visitors. The pictures and stories in them revealed the “othered” and conspicuous body: not just that of the punk subject, marked and pierced both by choice and by accident, but also Toledo’s own. As a Mexican female artist, she writes in an essay, hers was an experience not unlike a punk’s, of “knowing herself [to be] an outsider.”

Toledo is interested in flipping the gaze between polarities: her and him, white and nonwhite, funny and painful, rock star and groupie, order and chaos, exploitation and idealization, center and periphery. The title of her exhibition is taken from a quote attributed to Mark Twain: “History does not repeat itself, but it often rhymes.”

A version of this story originally appeared in the Spring 2019 issue of ARTnews on page 101 under the title “Around Mexico City.”

[ad_2]

Source link