[ad_1]

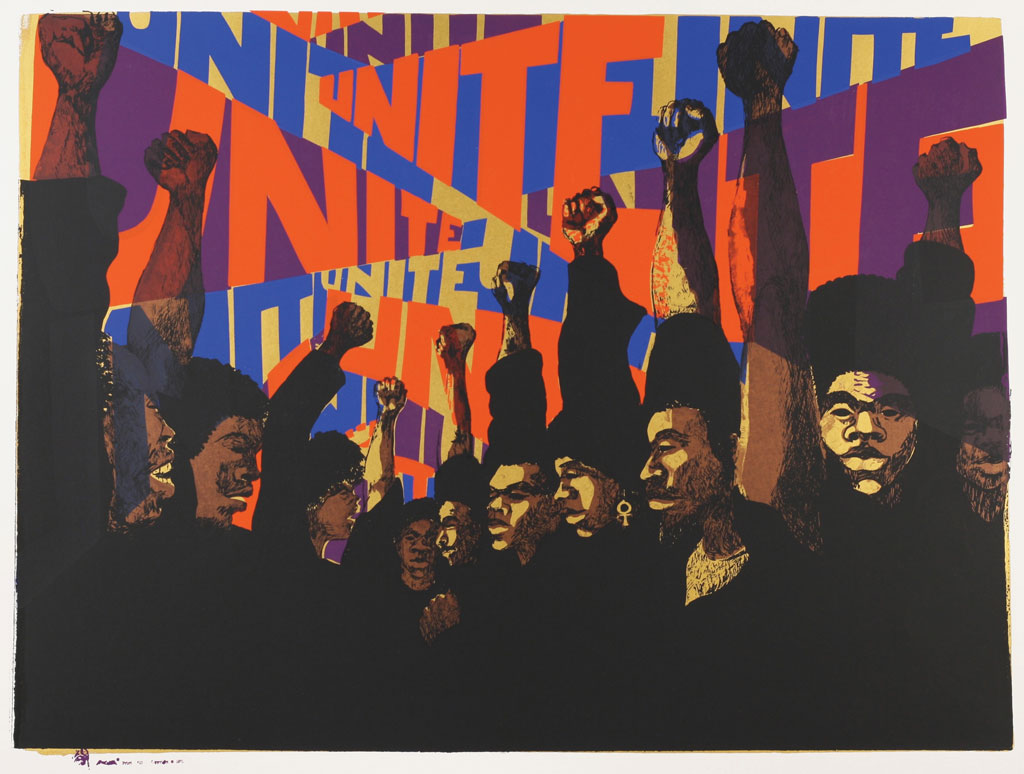

Barbara Jones-Hogu, Unite, 1969-71, screenprint, 22½” x 30″.

©ESTATE OF BARBARA JONES-HOGU/COURTESY LUSENHOP FINE ART

Several recent exhibitions in London have renewed questions about a so-called black aesthetic. If it exists, how would one define it?

The largest and most high-profile of these shows was Tate Modern’s highly anticipated “Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power,” which tracked black art in America from 1963 to 1983, two decades of great change and upheaval. (The exhibition is currently on view at the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas.) Curators Zoé Whitley and Mark Godfrey assembled over 150 works by more than 60 artists, varying in expression, intention, and materials, and undergirded their show with a strong theoretical framework. There were galleries devoted to themes, movements, artistic styles, collectives, exhibition spaces, and cities. The late Barkley L. Hendricks was dutifully represented in room 9 for “Black Heroes” with multiple works, including a nude self-portrait, Brilliantly Endowed (Self-Portrait), 1977. Betye Saar assembled freedom with everyday objects as seen in The Liberation of Aunt Jemima (1972). Seen for the first time in the U.K. was David Hammons’s body print Injustice Case (1970), in which a print of his own naked body is framed by a sullied American flag depicting a gagged and bound Bobby Seale in court during his infamous 1969 trial with the Chicago Eight. The black light in Roy DeCarava’s Five Men, 1964 (1964) and the superrealism in Faith Ringgold’s hulking American People Series #20: Die (1967) stopped viewers in their tracks.

The emancipation of several African nations in the 1960s inspired African-American artists to visit the continent, among them members of the Chicago-based collective AfriCOBRA (the African Commune of Bad Relevant Artists), founded in 1968. The group asserted the need for a shared aesthetic principle of positive images, rhythm, and direct affirmations through printed language created in bright Kool-Aid colors that have the power to define and direct, as evidenced in Barbara Jones-Hogu’s Unite (1969–71). Their work stands as a testament to “the expressive awesomeness that one experiences from African art and life in the U.S.A.,” as described by cofounder Jeff Donaldson in the collective’s manifesto.

Meanwhile, at Tate Britain, a photography exhibition illuminated aspects of black life in the U.K. during the same era. The bulk of the 30 photographs in “Stan Firm inna Inglan: Black Diaspora in London, 1960–70s”—which closed in November after a year on view—came from a group of works donated to the museum by modern photography expert Eric Franck and his wife, Louise, who worked closely with the photography nonprofit Autograph ABP to diversify the collection.

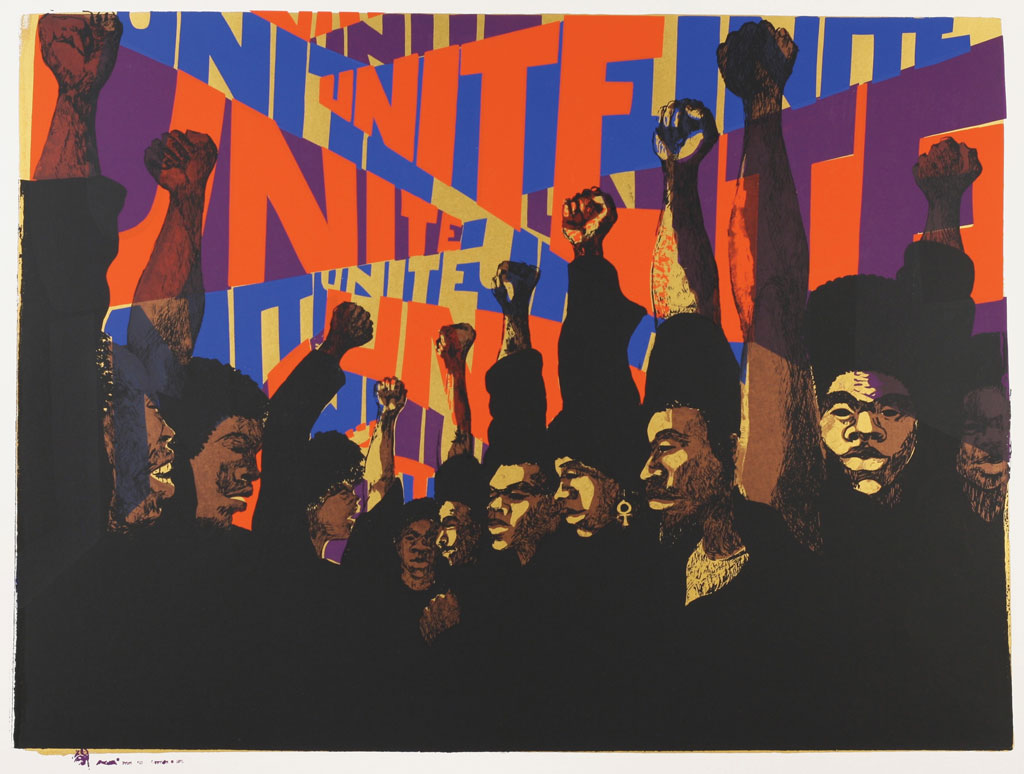

Raphael Albert, Miss Black & Beautiful Sybil McLean with fellow contestants, London, 1972.

©RAPHAEL ALBERT/COURTESY AUTOGRAPH ABP

Curators Elena Crippa, Allison Thomspon, and Susana Vargas Cervantes took the exhibition’s name from Jamaican dub-poet Linton Kwesi Johnson’s 1978 poem “It Dread Inna Inglan” (“Maggi Tatcha on di go wid a racist show but a she haffi go / African, Asian, West Indian an’ Black British, Stand firm inna Inglan. . . .” ). Johnson’s distinctive form of spoken-word performance with music—a photograph of him recording the poem shows him on a dimly lit stage, his arms coolly folded—articulated the double displacement of an Afro-Caribbean black living in England, diaspora upon diaspora.

By the time Johnson joined his mother in London’s Brixton neighborhood shortly after Jamaican independence in 1962, there had already been more than a decade of movement of black people from the colonies in the Caribbean to the “mother country.” The docking of the SS Empire Windrush passenger liner in London in 1948 marked the beginning of a mass migration. The photographers represented in “Stan Firm inna Inglan”—Raphael Albert, Bandele “Tex” Ajetunmobi, James Barnor, Colin Jones, Neil Kenlock, Dennis Morris, Syd Shelton, and Al Vandenberg—captured the strength of this growing community as its members engaged in resistance, rebellion, and culture.

Grenada-born Albert’s photographs of the “Miss Black and Beautiful” and “Miss West Indies in Great Britain” beauty pageants constitute an archive of black British style. Hearing the global chant of “black is beautiful,” Caribbean-born black women in West London were defining the parameters of their femininity within a British context but outside their ideals. In one still, pageant winner Sybil McLean smiles, her new title draping her torso and her crown sitting atop her cropped baby afro, as her fellow contestants brush her cheeks with congratulatory kisses. What comes across in Albert’s photographs, beyond the women’s beauty, is their collective celebration of Afro-Caribbean womanhood, self-actualization, and self-fashioning.

Colin Jones, Round the Back, The Black House, London, 1973–76.

©2018 COLIN JONES/COURTESY THAT ART GALLERY, BRISTOL, U.K.

Jones used photography to reveal the truth, and change minds, eventually earning the sobriquet the “George Orwell of British photography.” In 1973 the Sunday Times Magazine commissioned the ballet dancer-turned-photojournalist to document the lives of residents at a local youth hostel in Islington, North London, for a series with the title “On the Edge of the Ghetto.” The Harambee housing project (Harambee is Swahili for “pulling together”) had been established by Caribbean community leader Herman Edwards; the dilapidated terraced house on Holloway Road was a solace for disengaged black British youth and young families, who were short on education and employment. Rehabilitating and supporting the younger generation were its foundational principles, but the public saw it otherwise. Fueled by sensationalist media and anti-immigration legislation, many Londoners viewed Harambee as an incubator for black criminals. The press had dubbed it the Black House, and Jones’s profile served as a counter-narrative. In one of his photos, two slim but sturdy young men prop themselves against a concrete wall in anticipation of the shutter’s release; behind them, graffiti on the wall declares “war” and “Black power.” Far from criminal, the men project an aura of ordinary teenage ambivalence; they seem to take pleasure in posing for the camera.

Self-taught, Kenlock became the official photographer of the Black Panther movement in London. The Panthers operated out of Brixton, a black neighborhood where immigrants from the Windrush generation first settled (it has now succumbed to London’s sweeping gentrification). Kenlock recorded scenes such as a young woman pointing, with mild amusement, to the words “Keep Britain White” scrawled across an office door. Not unlike public notices announcing “no Irish, no Blacks, no dogs,” such an indignity was nothing new. When hundreds gathered outside the American embassy to protest the treatment of black Americans and to support struggles for emancipation around the world, Kenlock was in the midst with his camera. He also recorded the mass demonstration in 1970 that led to the court case of the Mangrove Nine and the first judicial acknowledgment that racism had been involved in the Metropolitan police’s practices.

Lubaina Himid, Le Rodeur: The Exchange, 2016, acrylic on canvas, 72″ x 96″.

ANDY KEATE/COURTESY THE ARTIST AND HOLLYBUSH GARDENS, LONDON

This past December, Lubaina Himid, 63, became the oldest artist and first black woman ever to win the prestigious £25,000 Turner Prize. Himid comes out of the BLK Art Group which, on October 28, 1982, facilitated the First National Black Art Convention, put together by a group of determined black art students at Wolverhampton Polytechnic as a forum for discussion about “the form, function, and future of black art.” BLK Art Group was both inspired and promoted by the cultural theorist Stuart Hall, who was one of the main proponents of reception theory (the theory that texts have no inherent meaning but are constructed by readers’/viewers’ particular cultural background) especially in relation to race and the media. Artists associated with the BLK Art Group—including Himid, along with Keith Piper, Sonia Boyce, and Maud Sulter—went on to establish the 1980s Black Arts Movement (BAM) in the U.K.

Himid’s nomination was based on her recent work, on display in solo exhibitions at Modern Art Oxford and Spike Island in Bristol, as well as earlier work that appeared in the group show “The Place Is Here.” The latter was a survey of black British art of the 1980s that traveled from Nottingham Contemporary to the South London Gallery. The room at Ferens Art Gallery in Hull that housed her Turner-nominated artworks spilled over with color, high drama, visual noise, and intensity. Born in Zanzibar and raised in England, Himid has made a practice of interrogating the legacy of European masters. Her training as a set designer came through in the centerpiece, A Fashionable Marriage (1987), which transformed William Hogarth’s famous painting Marriage A-la-Mode: 4, The Toilette (The Countess’s Morning Levee) (1743) into a large-scale installation composed of wooden cutouts on a stage. Hogarth was critiquing the excesses of affluent 18th-century London. Himid makes the black figures—slave-servants in Hogarth’s original—larger and places them center stage in opulent dress. The castrato is reimagined as a critic who “loves art but hates artists”; his embroidered coat is made from clippings from revered art magazines, and condoms. The countess and her lover are transformed into Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher (today we might replace them with Donald Trump and Theresa May).

Lubaina Himid, A Fashionable Marriage, 1987, installation view in the 2017 Turner Prize exhibition, at Ferens Art Gallery, Hull, United Kingdom.

©2017 TATE PHOTOGRAPHY

Himid’s more recent paintings, from the 2016 “Le Rodeur: The Exchange” series, made for subtler storytelling. The Rodeur was a ship loaded with 162 enslaved Africans that set sail from the Bight of Biafra in 1819, bound for Guadeloupe. During the voyage, an eye disease broke out, rendering all but one of the passengers blind. Some were thrown overboard in hope of insurance compensation. Those who arrived in Guadeloupe are said to have used the herbs and rituals of the indigenous peoples to restore their sight. The black figures in Himid’s paintings float above or stand in a surreal landscape, arms reaching out, eyes gazing randomly—it is unclear whether or not they can see.

This past summer, a mural on one wall of the Tate’s new experimental venue Tate Exchange looked at aspects of black female subjectivity. The sprawling cutout vinyl wall map, made by the research-led artist collective Thick/er Black Lines and entitled “We Apologize for the Delay to Your Journey,” described and name-placed current and historical artistic production by black British women. Included was the name of Khadija Saye, a 24-year-old artist who died in the Grenfell Tower fire last June, just a month after her work appeared in the 57th Venice Biennale. Thick/er Black Lines came together out of conversations at a residency called Psychic Friends Network that American artist Simone Leigh did at Tate Exchange in late 2016. Over the course of a week, participants listened to former Black Panther Party president Elaine Brown’s 1969 album, Seize the Time; artist Lorraine O’Grady encouraged visitors to ask her anything about aging; and Rashida Bumbray danced a spellbinding performance of Aluminum. Thick/er Black Lines wasn’t the only thing to come out of the residency. Shortly after it, Leigh initiated the UK chapter of Black Women Artists for Black Lives Matter.

Every fixed notion of “black aesthetics” or “black art” has its share of skeptics and challengers. In her 2017 book, Black Post-Blackness: The Black Arts Movement and Twenty-First-Century Aesthetics, Margo Natalie Crawford coined the term “black post-blackness” as another way to think about the “changing same”—a bounded circulatory relationship between the lived experience of blackness and the translation of said experience through art. Frantz Fanon asserted that the most radical black aesthetics movements foresee the next step, i.e., “beyond blackness” and use the available resources to inform new imaginings. The space between black consciousness raising and black experimentation is in constant flux. It cannot be contained.

A version of this story originally appeared in the Spring 2018 issue of ARTnews on page 106 under the title “Around London.”

[ad_2]

Source link