[ad_1]

By TOM LOEWY The (Galesburg) Register-Mail

GALESBURG, Ill. (AP) — Spend a few hours with Dr. Fred Hord and you’ll learn we are defined by many forces.

As the publication of “Knowing Him by Heart: African-American Makings of Abraham Lincoln” draws near, Hord took some time to talk about how he defines his own life.

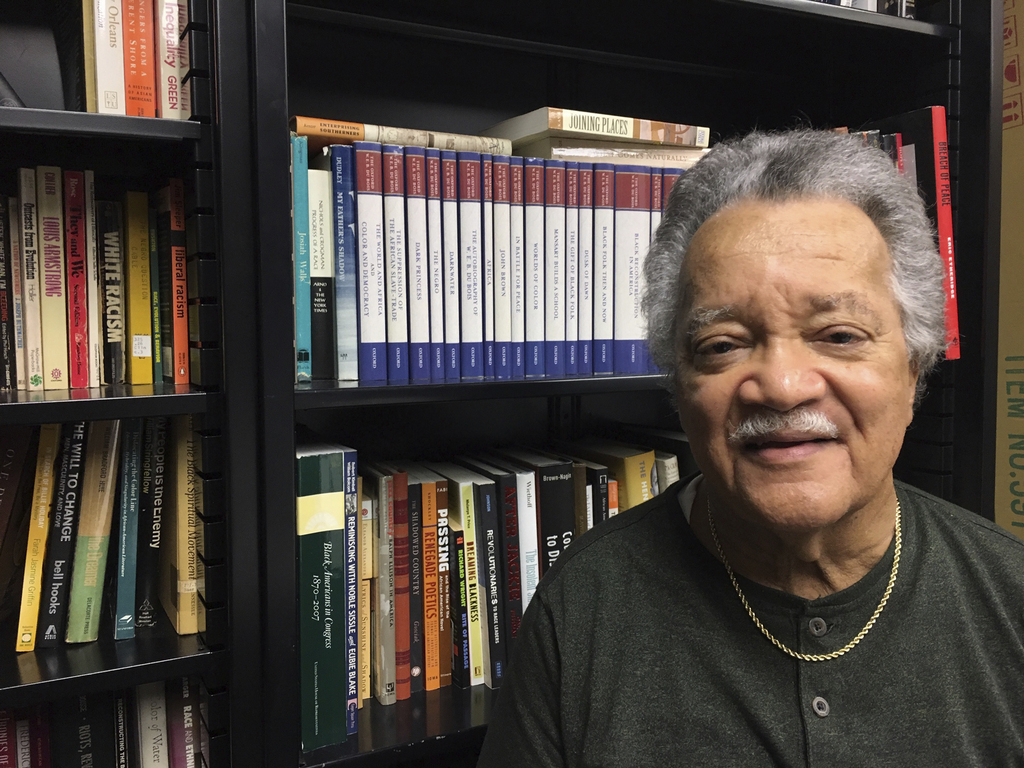

“One of my first memories, really, is being poor. Dirt poor,” Hord said recently as he sat in a small library inside the office of the Association for Black Culture Centers on the campus of Knox College.

“When I was a child, my job was to take the list of all the things we needed to Mr. Murtaugh. He owned the store,” said Hord, who was born in 1945 and spent part of his childhood in Terra Haute, Indiana. “I had to tell Mr. Murtaugh that we didn’t have enough money to pay him right away, but we would pay it all as soon as we had the money.”

Indiana was the epicenter of the modern-day rebirth of the Ku Klux Klan. The White supremacist organization held real political power — and a few of its members even taught the young Baptist minister’s son in public school.

Yet even Klan members don’t complain too much when a young man is a great athlete. Hord was a prep pitcher, and pitched on the same staff with the likes of Tommy John.

Hord can recall the days of segregation and the never-ending tension of integration, and he is a man who graduated from high school two years early. He married at 17 and graduated from Indiana State University in 1963 with bachelor’s degrees is speech and history.

He stayed on at Indiana State and by 1965 earned a master’s degree in speech and education.

“Then I went to work,” Hord said. “I had children to help raise.”

Student. Athlete. Scholar. Father.

Hord became an activist not long after finishing his master’s degree.

“By the time Dr. Martin Luther King was assassinated, I was angry. Very angry,” Hord said.

“People today would call me a radical. Radical. That’s a word.”

Hord offered an explanation.

“I grew up in a world where others could define your relationships and your life,” he said. “I remember, vividly, that after a classmate of mine, a Black classmate, was caught in a car with a White female student, a notice ran in the newspaper warning all young Black men not to be alone with White women.

“Told how to act. When I got older, I had mentors tell me, ‘Don’t be like Malcolm, be like Martin.’ People wanted to feel comfortable with Black activism. What I began to see was I couldn’t be a person just out for myself.”

Student. Athlete. Scholar. Father. Radical.

Now add poet after radical.

By the 1970s, Hord found himself sharing his words and thoughts with others. His first book of poems, “After H(ours),” was part of Third World Press’ prestigious First Poets series.

Throughout the 1980s, Hord continued to work and write. He went back to the world of academia and in 1987 was awarded a Ph.D. in black studies: literature and history from Union Graduate School at the University of Cincinnati.

Then the roles of scholar and radical converged. Hord found himself at the University of West Virginia, isolated and feeling “mounting frustration” as he served as the director of a Black culture center.

Black cultural centers began after student protests in the late 1960s — first at Rutgers University in 1967, followed by others at Knox College and the University of Iowa in 1968.

“But there was no link. No network,” Hord explained. “We had these culture centers and they were just out there on their own.”

At a 1987 meeting of the American Council on Education, Hord proposed creating a national network of Black culture centers. It was an idea that resonated, and from that gathering the Association for Black Culture Centers was formed.

Hord relocated to Knox College, got the ABCC network started and designed a fledgling Africana studies program for the liberal arts college.

About 50 people from roughly two dozen schools attended the first ABCC conference at Knox College, and the annual event has grown to between 200 and 550 attendees at its annual gatherings.

Student. Athlete. Scholar. Father. Radical. Poet. Organizer. Educator.

As the timeline wound down to the present, Hord talked about other book projects — and the editing efforts he shared with Matt Norman to bring “Knowing Him By Heart” to life.

“It’s a challenging book — not everyone has the same opinion of Abraham Lincoln,” Hord explained. “And the people speaking about him in the book range from the time frame of 1858 to 2009.

“What made the project so unique, I think, was that Matt and I wrote introductions for all the individuals who speak in the book.”

The man who is many things then settled on his own story.

“I pitched in a big game, a playoff game, when I was in high school,” Hord said. “And my dad drove a long way to come and see me play.

“I got down, I think it was 1-0 or 2-0 right away, in the first inning. But I shut it down, and I had my team behind me. And I came up late in the game and drove in the runs we needed and we closed it out and won.”

Hord almost allowed himself to smile at the memory.

“My dad meant a lot to me. Maybe I didn’t even realize how much at the time,” he continued.

“And he never said much. But after the game he came up to me and he asked if it would be OK if he drove me back home from the game. It was, and we got in that car.”

The student who was an athlete and would become a scholar and father and radical and poet and organizer and educator remembered being a son.

“We got into that car, and before my father started it he looked at me and he said, ‘You can get up. Know that about yourself. You can do it.’

“His entire life he showed me how to take responsibility. How to not talk about things and just do them. You always get up. That’s how I always wanted to be defined.”

___

Source: The (Galesburg) Register-Mail, https://bit.ly/2Hh56Uc

___

Information from: The Register-Mail, http://www.register-mail.com

[ad_2]

Source link