[ad_1]

By Mark F. Gray

AFRO Staff Writer

mgray@afro.com

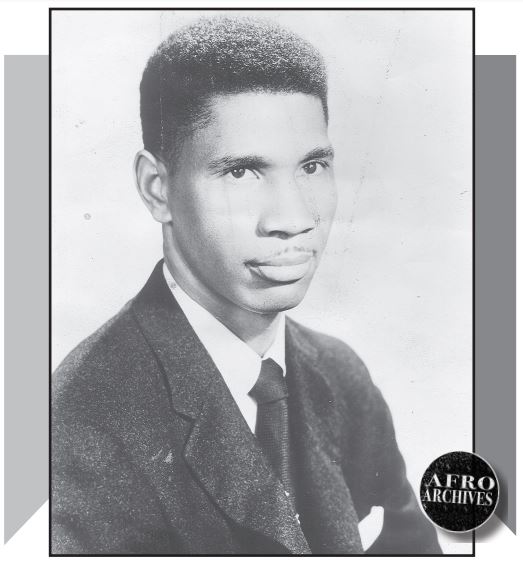

In many respects Medgar Evers’ life has been defined more by his death than his impact on the fight against systemic racism in the United States. If Evers hadn’t been assassinated in 1963 – the same year Camelot ended with the assassination of President John F. Kennedy – his place in civil rights history would resonate beyond a historic footnote similar to Juneteenth.

Evers led the march for desegregation of public schools in his home state of Mississippi as an activist following the Supreme Court’s landmark Brown v. Board decision which ruled segregated public schools were unconstitutional. In 1954 he applied to the University of Mississippi’s law school as he worked to overturn segregation at the University of Mississippi in a test case for the NAACP. Evers also fought against the vestiges of Jim Crow laws by pushing for the desegregation of public facilities, and the enforcement of voting rights throughout the state. However, when James Meredith broke that barrier in 1962, integrating University of Mississippi, Evers became something of an afterthought on the Oxford, Miss. campus.

Until last weekend, Mississippi was on the wrong side of history as one of the Confederate States of America that was governed by a state flag that still bears stars and bars representing systematic racism, oppression and slavery. Evers was way in front of the curve understanding how those conditions would ultimately affect his home state, and his activism as a national chair of the NAACP made him a target. Ultimately he became a victim to the bullet of a White supremacist Klansman, Byron De La Beckwith, who wasn’t convicted until a third trial in 1994.

Until July of this year, the flag with the stars and bars symbolizing the confederacy will wave – though not so proudly as some places in the south. The pushback against the tyranny that it represents remains, while the sentiment for which it stands has been shaken to the core by courageous southern athletes who have used their platform to address the issues and face similar threats.

NASCAR driver Bubba Wallace and Mississippi State running Kylin Hill have been thrust into the eye of the civil rights storm. Each has spoken and peacefully demonstrated against the American Swastika waving at their events which makes them targets like Evers nearly six decades ago. They’ve each used their platforms in sports to stand against the symbol of systematic oppression that some generations still hold on to.

Wallace, the only Black driver on the sports’ biggest stage, said the flag shouldn’t be waving at NASCAR events and the organization capitulated following George Floyd’s death. After the auto racing league ruled the racist symbol could no longer fly at its events there was a plane seen flying above the track with a tail and a massive Confederate flag featuring a sign reading, “Defund NASCAR.” The Sons of Confederate Veterans reportedly took responsibility for that stratospheric protest.

Wallace caught pushback when a noose was found in his garage at Talladega (AL) Motor Speedway prior to one of the more meaningful races in that sport. Ironically, the same FBI that was somewhat derelict in its duties when charged with shadowing Evers, investigated the noose incident for approximately a day and a half. Not surprisingly, they found NASCAR had nothing to do with the noose, saying it had been in the garage since October.

Hill struck a chord in the fanbase of Mississippi State football fans, and throughout the Southeastern Conference when he said he wasn’t going to represent the school anymore as long as the confederate flag was a part of his home state’s flag. The Mississippi native, who led the best conference in college football in rushing last year, said via Twitter “Either change the flag or I won’t be representing this State anymore & I meant that…I’m tired.”

He later explained that it was the symbol of what the flag means. “Unlike [the] rest I was born in this state and I know what the flag means.”

Nothing reverberates in the south more than college football and NASCAR. While the racing league has been reluctant to include minority drivers on it’s major circuit, the greatest benefactors of the desegregation of colleges have been athletic programs in the south. That has allowed Alabama, Florida, Georgia, LSU and Auburn to become consistent national powers. It also gave Hill a greater – more dangerous platform to stand on – when making his point. His posts and defiance led to Mississippi St. coach Mike Leach and the other major state school coach Lane Kiffin meeting with Mississippi Governor Tate Reeves to protect their recruiting bases by pressing forward with moving forward on a totally new flag that began last week.

The Mississippi State Legislature voted to remove the Confederate logo from its flag becoming the last state to remove the racist symbol over weekend.

Hill and Wallace have proven that Evers’ death was not in vain. Colleges in the deep south have been integrated and two athletes have answered the call for activism to effect significant change by helping to purge the nation of an inglorious past- although, like Evers, now each athlete has to watch his back.

[ad_2]

Source link