It is unlikely that this reaction will come as a surprise to Eminem, for whom rapping from the perspective of vicious killers seems to be a favorite conceit — from his iconic “Stan” (2000) to “Murder Murder” (1997) to “Kamikaze” (2018). But you have to wonder whether his point — which appears to be “aren’t murderers disturbing” — is too often made at the expense of victims, rather than perpetrators.

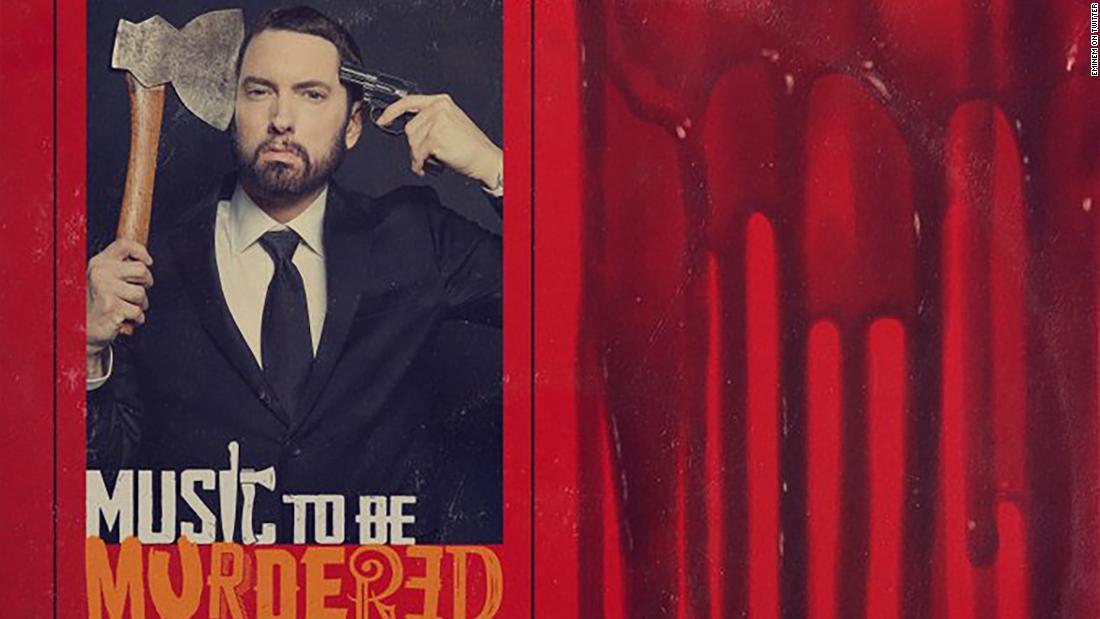

In “Music To Be Murdered By” alone,

Eminem compares himself to serial killers Richard Ramirez (known as the Night Stalker), Albert DeSalvo (known as the Boston Strangler) and Charles Manson. He also throws in a healthy dose of another of his artistic trademarks — pugnacious hatred of women, plus some outdated pop culture references to boot.

Eminem’s intent with the

album’s lead single “Darkness,” which focuses on the 2017 Las Vegas shooting, appears to be good. The delivery is extraordinary. His lyrics: “Finger on the trigger, but I’m a licensed owner / With no prior convictions, so loss, the sky’s the limit / So my supplies infinite, strapped like I’m a soldier,” make a jarring comment on the ease with which people can obtain firearms in America.

But the laden predictability of the storytelling, which sees “Darkness,” as usual, performed from the perspective of a heinous shooter — played, in part, by Eminem

in the music video — are liable to make the listener switch off.

Eminem’s flip-reverse trick also makes some risky assumptions when, as is the case in “Darkness,” the question of mental health is thrown into the mix. He raps that the shooter shows “no signs of mental illness,” but the chorus — which samples Simon and Garfunkel’s “The Sound of Silence” — resonates with loneliness, and heavily hints that the shooter is suffering.

It’s true that many people have hidden mental health problems, but drawing a direct line between people who are ill and people who murder — particularly in a case where the motive of the shooter remains officially unknown — makes potentially stigmatizing assumptions about the mentally ill.

And then, of course, there’s the misogyny.

“Unaccommodating”‘s

stale reference to a particular act in Kim Kardashian’s sex tape, which was leaked in 2007, is just another riff on a line he’s been repeating for 20 years.

Check his reference to Christina Aguilera in “The Real Slim Shady,” which was released almost two decades ago. The joke is the same, and always on the woman. As even a cursory glance at his back catalog will tell you, it’s far from his most grotesque.

“Kim,” from his 2000 LP “Marshall Mathers,”

describes Eminem’s real ex-wife’s fictional murder. It is an expertly composed, perfectly executed domestic violence fantasy underscored by acute male anger. The follow-up, “’97 Bonnie and Clyde,” details Eminem disposing of Kim’s body, accompanied by their young daughter Hayley.

Both are emblematic of a common theme in his early albums: loving tributes to Hayley, alongside literally dozens of songs which describe hateful acts toward women. It’s a kind of emotional dissonance familiar to women everywhere. It implies: This female is OK, because I sort of made her. But the rest of you are fair game. (Eminem

did offer a modest apology to his ex-wife on his 2017 album.)

There has been a litany of articles over the past couple of years detailing examples of early Eminem lyrics that would never fly if he released them now. He seemed to have semi-got the memo regarding homophobia. Or, at least, got the memo that homophobic slurs don’t get a pass anymore.

In a 2018 interview with Sway, Eminem admitted that he regretted the use of the f-word in reference to Tyler the Creator on his album “Kamikaze,” saying it was “too far,” and that he realized he was “hurting a lot of other people by saying it.” But he doesn’t appear to have extended that empathy to many others.

Throughout “Music to Be Murdered By,” the physicality and skill of Eminem’s rapping remain formidable. But the effect is to make the listener nostalgic for a time when his dark alter ego might still have scintillated. His outrageous talent, not to mention a healthy dose of white privilege in a historically black arena, have seen Eminem get away with more than most in the music industry.

More than two decades in, his “in the bad guy’s head” schtick is no longer subversive. His aim might be to expose the truth of how twisted a person’s mind can become. But by now, it feels like he’s exhausted every angle.