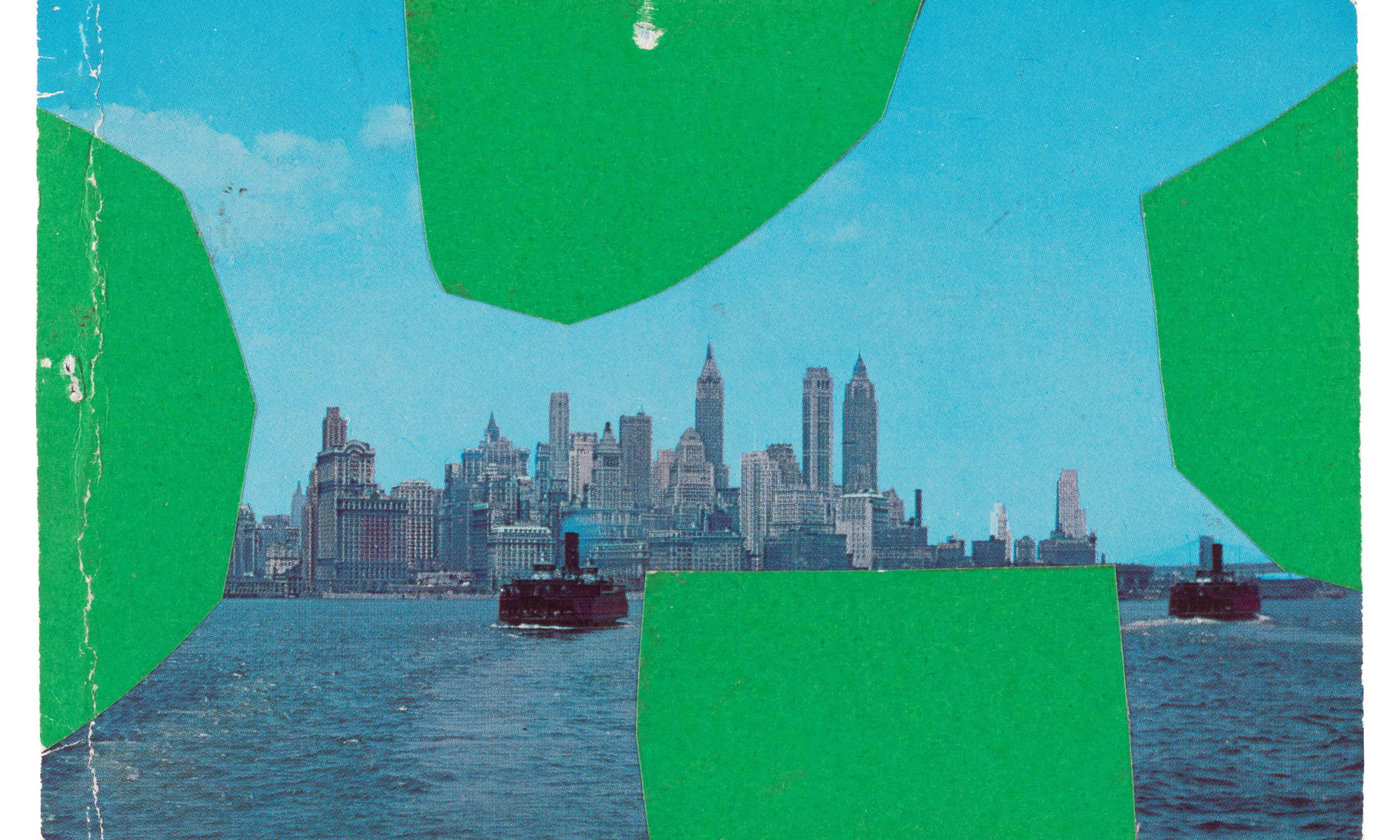

Ellsworth Kelly, Four Greens, Upper Manhattan Bay (1957)

© Ellsworth Kelly Foundation

There is a good reason for the Louis Vuitton Foundation in Paris to put on an Ellsworth Kelly exhibition. In 2014, the last site-specific commission to be completed in his lifetime was inaugurated in the building’s auditorium. The American artist, known for his work with solid colour, form and line, died in December 2015 aged 92.

Now the auditorium sits at the heart of an exhibition, Forms and Colours, 1949-2015, of more than 100 works by Kelly. Its stage curtain represents one of his Spectrum works—featuring dazzling vertical lines of rainbow colours—while single red, blue and yellow panels appear on the walls. “Kelly took a lot of pleasure in this commission; he was very involved,” explained Suzanne Pagé, the foundation’s artistic director at the opening on 4 May. “He had proposed the panels as his usual wooden ones, but that would have changed the finely tuned acoustics of interior that architect Frank Gehry had designed.” Instead, the artist—who loved the problem-solving aspect of art production—found a company that could produce a textile in a big enough size and to the exact colour of his paintings.

The stage curtain in Fondation Louis Vuitton’s auditorium, featuring one of Ellsworth Kelly’s Spectrum works

© Ellsworth Kelly Foundation, © Fondation Louis Vuitton / Marc Domage

The exhibition has travelled from the Glenstone Museum, the private institution not far from Washington, DC, which has a huge Kelly collection, but has arrived in Paris in a much-modified form. This show tells the whole story: Kelly benefitting from his GI grant—provided to veterans of the Second World War—and spending six years in Paris, where he was inspired by Hans Arp and John Cage to begin incorporating chance into his practice (there’s a 1950 Cut Up drawing here, with ink-blackened paper squares scattered on a ground). Also his return to the US in 1954, where he finds that though he was too American for the French, he’s also too French for his muscularly Abstract Expressionist peers in the US.

Instead, Kelly remains outside of all movements. He deals not in narrative, but in space and the physical effect of colour. He develops an economy of form that is reductive but somehow playful and often quite pretty. He works around the fine line where painting and sculpture meet.

Installation view of the auditorium at Fondation Louis Vuitton

Ellsworth Kelly Foundation. Photo: © Fondation Louis Vuitton / Marc Domage

There are more than a few greatest hits here. The show includes, for example, his so-called first and only Abstract Expressionist painting, made after a visit to Giverny in 1952, with a stunning mottled green surface that owes much to Monet; and the Yellow Curve floor sculpture from 1990—a thin flat panel installed on the ground of a specially created room—that floods the space with yellow light. Also featured is a 1987 painting made of three separated dancing grey shapes (in oil on canvas), in which the wall is as much a part of the piece as the panels themselves.

Ellsworth Kelly, Yellow Curve, 1990

© Ellsworth Kelly Foundation. Photo: © Ron Amstutz;Courtesy Glenstone Museum, Potomac, Maryland

Kelly’s work is entirely phenomenological—completed by viewer and context. And even when he turns his hand to other things, he is manifest. In a series of photographs of buildings and landscape, he seeks out blocked forms and lines. The picture postcards he sent to friends are embellished with coloured shapes. Drawings of fruit and vegetables are reduced to the absolute essentials.

While the exhibition suffers from trailing across some fairly disconnected galleries (it would be easy to miss a section or two), it benefits from little or no interpretation. Just a text at the beginning of each gallery serves to highlight a few facts, but quite rightly, this is presented as a show not to be read about, but to be seen and felt.