[ad_1]

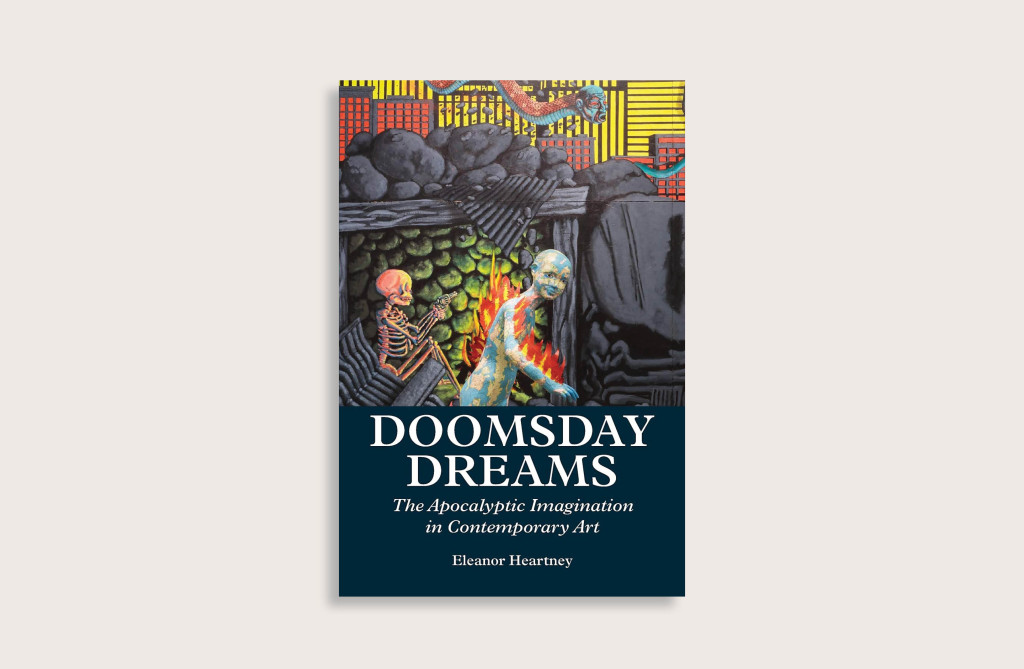

A.i.A. contributing editor Eleanor Heartney’s book Doomsday Dreams: The Apocalyptic Imagination in Contemporary Art, recently published by Silver Hollow Press, considers the various ways contemporary artists have approached the theme of the end of the world, an idea that she describes as “deeply embedded in almost every aspect of Western culture,” including our understanding of time, social upheavals, and notions of perfection and progress. “Is there a way to imagine the End that doesn’t consign huge swaths of the human race to death and destruction? Is there a way to reconfigure Paradise and its promise of regeneration without succumbing to sectarianism and strife?” Heartney asks. Artists, she argues, “can help us understand the continuing hold of the apocalyptic imagination”—and perhaps also point to ways beyond it. In the book, Heartney surveys the history of apocalyptic imagery, from its emergence in the sacred texts of the ancient Zoroastrian Avesta to Cold War–era responses to the threat of nuclear annihilation, before turning to its use by contemporary artists as a means of addressing subjects like ecological crisis, religion, ethics, and political struggle. In the following excerpt, Heartney explores the work of video and installation artist Douglas Gordon, whose work since the 1990s has often returned to the theme of the battle between good and evil. –The Editors

The literary canon has been greatly enriched by complex sagas that mirror the breadth and symbolic import of the narratives found in ancient apocalyptic texts. The sweeping historical arc which draws humankind inexorably from creation to the ultimate battle between good and evil has inspired creators as diverse as John Milton, William Blake, J.R.R. Tolkien, and Kurt Vonnegut. Contemporary visual artists also create eschatological fictions to grapple with the problem of evil, the alien nature of the ‘Other’ and the inexorability of history. In creating elaborate alternative worlds shaped by the conflict between opposing moral forces, some artists reference specific literary works, while others simply borrow their ambience and narrative arcs.

In the works of artists like Trenton Doyle Hancock, Gary Panter, and Matthew Ritchie, the conflict between good and evil plays itself out within imagined worlds where the massed forces of one order ultimately triumph over those of the other. These works are fictional kin of our own Clash of Civilizations and center on the outsourcing of evil to some fearsome Other who must be defeated for the righteous to prevail. But in another version of the Grand Battle, good and evil are engaged in a struggle within the divided self. Here the battle lines are not so definitively drawn and victory is always shaded with elements of self-destruction. This is the cosmos that enthralls British artist Douglas Gordon.

Gordon is known for works that reconfigure Hollywood movies in ways that alter our sense of time and our expectations of narrative. His best-known work is 24 Hour Psycho (1993), in which the iconic Hitchcock film is slowed down to fill a entire day. In another work, from 1999, Otto Preminger’s 1949 thriller Whirlpool is presented on two adjacent screens, one flipped so that they provide mirror images, and edited into sequences of odd and even frames. The work’s title, left is right and right is wrong and left is wrong and right is right suggests the uncertain status of these subtle manipulations of the original film. In Déjà-vu (2000) Gordon’s raw material is Rudolph Maté’s 1950 film noir D.O.A., about a poisoned man attempting to discover his murderer during his last hours of life. Playing on the multiple time frames in which the original narrative unfolds, Gordon presents the film on three screens, one played at normal speed, one shown at slightly accelerated speed, and the other slightly slowed down.

Such works have been discussed in relation to cinema’s manipulation of the experience of time, the blending of fiction and reality, and psychoanalytic notions of memory, mirroring, and consciousness. But, as many commentators have pointed out, an equally important source for Gordon’s fascination with doubling, splitting, mirroring, and inverting is his Scottish heritage and personal history. Gordon had a complicated religious upbringing. He is the child of Calvinist parents whose mother became a Jehovah’s Witness when he was six years old. Jehovah Witnesses adhere to the principle of Biblical inerrancy and sharply disassociate themselves from what they believe are the Satanic influences of both secular society and the teachings of other religions. As a millenarian Christian sect, members see the world in terms of a stark opposition between good and evil. They believe that Armageddon is imminent, after which the elect will join Jesus to rule over a purified earth. Gordon himself acknowledges the impact of his exposure to this religion. He says, “But one of the ideas the Witnesses have is that there are 144,000 saved—the elect—and most of us aren’t part of that. So there was an absolute feeling of otherness because you weren’t mainstream within religion, or part of mainstream culture.”

For Gordon, this sense of otherness was replicated in multiple levels, from his own childhood home where two versions of Christianity were in play, to his identity as a Scotsman in the British Isles. Historically at odds with the English majority, Scotland was swept during the Reformation between the shifting dominance of Catholicism and Protestantism, both of which retain significant constituencies there today. Meanwhile, the country remains roiled by questions of Scottish independence and by historical divisions between the sparsely populated Highlands and the more urban Lowlands. These ideological and social disjunctures have given rise to a state that was dubbed the “Caledonian Antisyzygy” by the Scottish literary critic G. Gregory Smith in 1919: the “idea of dueling polarities within one entity,” which various theorists have maintained is a distinctive feature of Scottish psychology and literature.

In various works, Gordon has paid homage to three of the most prominent Scottish exemplars of antisyzygy: Robert Louis Stevenson’s 1886 The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde; that novel’s lesser known antecedent, The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner, published in 1824 by James Hogg; and psychiatrist R.D. Laing’s influential 1960 book The Divided Self: An Existential Study in Sanity and Madness. The novels both tell tales of individuals pulled between two distinct identities, one manifesting itself in ordinary good and the other in absolute evil. They differ in that Stevenson’s malevolent Mr. Hyde is the result of a bungled scientific experiment by his alter ego Dr. Jekyll, while Hogg’s justified sinner, Robert Wringhim, is unhinged by his religious beliefs. The plot centers around Wringhim’s encounter with a mysterious stranger named Gil-Martin who may be the devil or may be his alter ego. Encouraged by Gil-Martin, Wringhim murders his brother under the delusion that, because he is predestined to be “saved,” he can do no wrong. The structure of the novel is bifurcated into two versions of the same events, one related by a dispassionate Editor and the other by the tortured protagonist whose memoir is discovered after his death.

Both these novels served as grist for Laing’s theories about the “divided self,” which gained a large following during the 1960s. Laing rejected conventional wisdom about the nature and causes of schizophrenia. Disputing the primacy of reason over madness, he argued instead that childhood experiences of the mentally ill create a rift between “real” and “false” selves resulting in forms of psychosis that are actually simply sane responses to an insane world.

Gordon blends this “divided self” with a religious cosmology of good and evil to produce works whose points of view are deliberately ambiguous. One of the simplest of these is a 1996 video titled, after Laing, Divided Self I and II. This work presents two monitors each offering a looped clip of two arms struggling for dominance. Though they appear distinct, as one is hairy and the other smooth, both belong to Gordon and are his realization of a passage from Stevenson’s novel in which the metamorphosing Dr. Jekyll reports looking at and not recognizing his own arm.

Gordon references Hogg and Stevenson in his 1995–96 video installation Confessions of a Justified Sinner. Here, two large projection screens present continuous loops of the transformation scene from Rouben Mamoulian’s 1931 black-and-white film version of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, one positive and the other negative. They endlessly change back and forth, suggesting no resolution to the struggle between the protagonist’s alternative personalities. Gordon returned to this theme in a 2002 exhibition titled “Confessions,” which was presented at Kunsthaus Bregenz in Germany. This three-part installation comprised three takes on Hogg’s book: a handwritten transcript of the portion of the narrative devoted to Wringhim’s confession, a darkened room illuminated by black light in which a disembodied voice recites this same text, and finally, a video projection titled Fog in which a young man who resembles Gordon simultaneously emerges from and disappears into a mist, as if merging with himself. The idea for the show, Gordon noted to a writer, “came from one point in the book where Wringhim has finally realized his descent into madness; he tries to warn the world of the dangers of flirting with the devil by writing his confessions, but no one will print them.”

In these works, Gordon explores the intermingling of vice and virtue within a single identity. He personalizes this struggle in various ways—using an actor who resembles himself in Fog; incorporating Robert Wringhim’s name in his own email and address; and in a related photographic diptych titled Monster (1996–97). This latter presents a pair of self-portraits, one of which offers an unexceptional frontal view while the other takes the same pose but presents Gordon’s face demonically altered with scotch tape.

Gordon’s most powerful statement about the mirror quality of good and evil is his 1997 work Between Darkness and Light (After William Blake). Here two films, The Song of Bernadette (Henry King, 1943) and The Exorcist (William Friedkin, 1973), run simultaneously on the same projection screen. Because the original films differ in length, the continuous loop creates ever changing and serendipitous moments of coherence and contrast that emphasize their common theme of supernatural possession. The two films are, to borrow a phrase from Dr. Jekyll, “polar twins”; in one, a young girl is overtaken by Satan, in the other, her counterpart is overtaken by visions of the Virgin Mary. The device of the overlay creates chance events with surprising synergy, and as the two sets of characters merge, their distinctions begin to disappear. The disbelieving nineteenth century French villagers and skeptical modern doctors, the bile spilling demon and the beatific saint, become part of a single narrative of irrational forces tearing through the façade of ordinary life.

Between Darkness and Light was originally created as part of a sculpture festival in the town of Muenster, Germany. Gordon was invited to create a work somewhere in the city, and after much deliberation chose to place it in the middle of a dank pedestrian underpass that smelled of urine. Explaining his choice, he remarked, “I started to think about the underpass as some sort of purgatory. It’s neither in the city nor out of it. It is neither in heaven nor in hell. I began to think that it might be interesting to try and stop people passing through it as quickly as they might have done normally. If I could find a way to make people hang around there for some time, then it would become a space for thinking, reflecting and waiting to see what might happen next . . . . It was like a perfect model of purgatory.”

In another interview he elaborated on his vision of purgatory: “Growing up with some idea of Catholicism as exotic, I was always interested in purgatory. Not that I believed in heaven or hell; I was much more interested in the purgatory idea and the fact that it became a powerful political and economic means for the Catholic Church to control people. . . . The thing that intrigued me was the half-full/half-empty; people who are quite bad, but not bad enough, and quite good but not good enough— how do they float about in purgatory and have a discussion together?”

Reflecting on the internalized struggle of good and evil, Gordon has come to a different conclusion than St. Augustine. While the fifth century Church father argued optimistically that evil is the absence of good, making it the less powerful half of the dyad, Gordon takes the opposite position. Pointing to the ultimate triumph of the Hydes over the Jekylls and the Gil-Martins over the Wringhams of the world, he remarks, “One of the most appealing things about the idea of your doppelgänger being more powerful than you is because the bad can adopt good as a disguise, but a good person cannot adopt evil. You can’t pick it up and throw it away. Evil is meant to be innate, but goodness is something evil can adopt at any moment.”

[ad_2]

Source link