[ad_1]

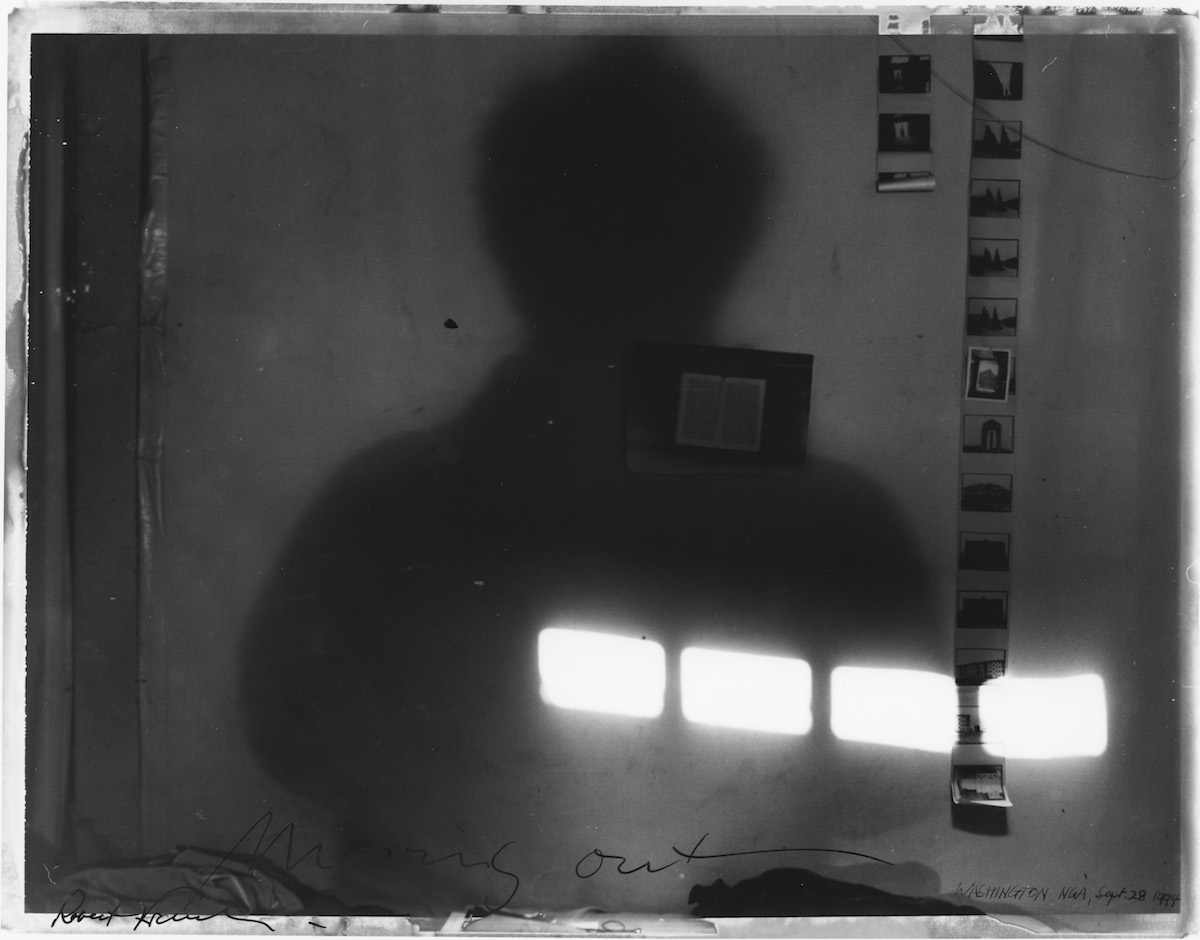

Robert Frank, New York City, 7 Bleecker Street, September, 1993.

©ROBERT FRANK/COURTESY PACE/MACGILL

When Robert Frank died two weeks ago at the age of 94, filmmakers and photographers around the world took to a variety of platforms to remember the artist’s profound impact. Born in 1924 in Zurich, Frank first became widely known for his photographs of America—with many of his most iconic images appearing in his 1958 photo-book The Americans, which has been considered by many to be one of the most important photographic series ever created. Frank, who was also a prolific experimental filmmaker, also touched many who came after him as a mentor, friend, or an influence. To learn more about his impact, ARTnews spoke with artists, curators, and Frank’s gallerist.

Dawoud Bey

Artist

Robert Frank not only changed the way photographs were made but the way we read, respond, and think about them. In the simmering aftermath of the post-Eisenhower years, he brought his incisive outsider’s vision to America, penetrating the placid social veneer to get at the messy and uneasy underbelly of the country’s relationship with itself.

Doing so required both a deftness of seeing and a way of use of the small handheld camera that was an act of exquisite improvisation; quickly framing the subject(s) within the space of the picture in such a way as to amplify the thing that was both visually poetic, deeply insightful, and maybe unsettling, and just as often, full of passion and love. Robert Frank taught us that the camera, attached to an active and engaged critical mind, could reveal the world to us in ways that made us all more alert. What a big heart and a brilliant eye he had.

Sarah Greenough

Senior Curator and Head, Department of Photographs, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

When I first met him, in 1990, I vividly remember the sense of meeting a rock star—someone who had so influenced my life up until that point. The museum had only decided earlier that year to officially start collecting photography, and I met Robert a few months after that, when he was looking for an institution that would preserve his work and be the repository for it. Through our conversations, he selected the National Gallery to be that home for a very large archival collection, which included all the negatives, contact sheets, and workprints for The Americans, plus a large collection of vintage exhibition prints made from his early years in Switzerland through the late 1980s and early 1990s, and unique bound volumes of photographs.

It was a really long friendship—certainly one of the most important ones I’ve had in my life. It’s very intimidating to meet someone [like that], but I found him always to be incredibly warm and generous. He had a reputation of being a recluse, and he definitely was. Robert hated to wear the mantle of fame. He was always pushing, striving, trying to make art that would be more truthful, as he would say, so he would resist any kind of adulation. He was very much a Beat artist—somebody who rebelled against all the constraints of society.

There were things about him that were very Swiss, very organized. He lived in this totally chaotic world, but when you dug beneath the surface of it, there was a sense of organization. That became apparent when he began sending the contact sheets and workprints for The Americans. Many of them arrived curled up, but once we started flattening them out, they were all numbered, and those numbers corresponded to the ones on the negative sheets, which corresponded to numbers on the strips on film. What looked like boxes and boxes of chaos proved to have this reasonably logical order to it.

The Americans was reviled by critics [when it was first released as a photobook in 1958] and was said to have been made by a sad, sick person. Almost immediately artists and others understood it for what it was. The Americans was one of the things that made me realize what a profound influence photography could be on our lives. He changed the course of 20th century photography, and that is not an exaggeration.

Ed Ruscha

Artist

I saw The Americans in 1959. It was like opening a book laced with dynamite. No one had ever told the story of America in such a way. The fact he was Swiss, and not American, made the difference. A foreigner sees America in a totally new and different way. In the 1970s, he and his wife, June [Leaf], lived across the courtyard from me in Hollywood. People would ask him what he was photographing and he would say he was no longer using his camera.

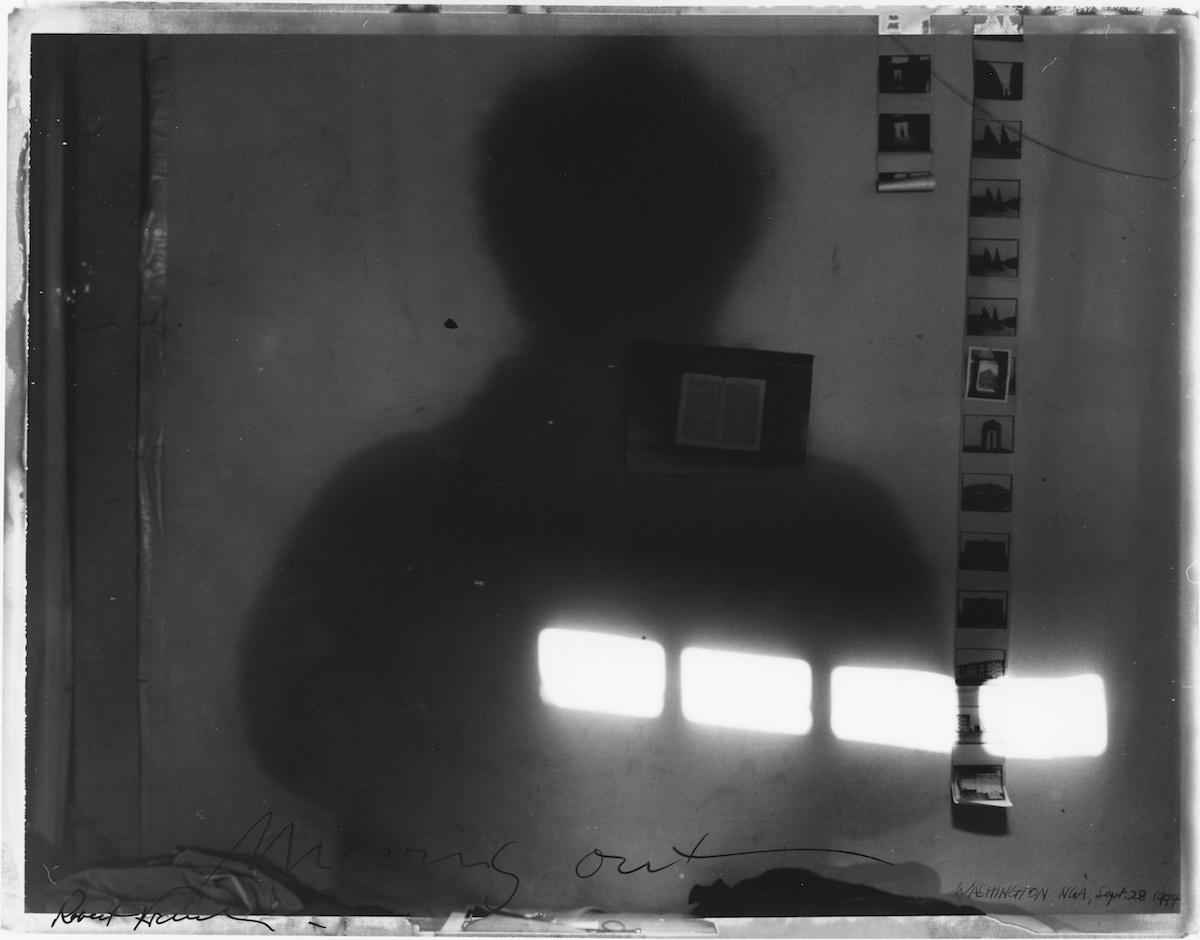

Robert Frank, Wales, Ben James, 1953.

©ROBERT FRANK/COURTESY PACE/MACGILL

Anne Tucker

Curator emerita, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

In 1983, we purchased a complete set of The Americans. That led to Robert agreeing to let us do a retrospective. It was not without difficulties. Robert would stand back and let you flail. And then there would be a, “Well, what if…” We bought other pictures, and Robert gave us some additional photographs. Robert’s capacity as a mentor may have only been “Keep working,” but he was incredibly generous about letting photographers knock on his door.

Of all the artists I’ve worked with, he was the most secure in what he wanted and how he wanted done. There is a myth that Robert wasn’t a good printer—that his photographs were overexposed. Overexposed by whose standards? No, they were exactly what Robert wanted, and he had his own vision. I loved working with him. If he detected bullshit, he didn’t want to talk to you, and boy, did he have that detector.

[As part of the 1986 Frank retrospective at the MFA], we showed Cocksucker Blues [his 1972 documentary about the Rolling Stones]. It quickly became apparent that we had to rent a theater instead of showing it at the museum because of the demand. My director [Peter C. Marzio] was standing in the lobby, trying to greet every trustee coming in. He was saying, “Now, this is a difficult film.” There was one woman, a high-level trustee from Exxon, who came. On Sunday morning, Peter came in, and there was a note with a little white logo in the upper left corner—the Exxon logo. He thought, “Ohhh, no.” He opens it up, and it says, “Dear Peter, I wondered what was going on in the world as I was forging my way as a young person on Wall Street. Now I know.” Even she recognized that in that film, however offensive it may have been, there was a reality. That’s what I miss so much about Robert.

Marian Luntz

Film curator, Museum of Fine Arts, Houston

When Anne started spending time with Robert and his photographs, the museum’s film curator at the time, Ralph McKay, told her to ask Robert about showing his films. We assisted him on an early preservation project on Pull My Daisy [1959], and we wanted to help create what we call a repository, a centralized place where his prints and negatives could be. The films screened here, as part of [Frank’s 1986 retrospective], and we initiated what became a distribution arrangement. We now have a circulating collection of Robert’s films, from Pull My Daisy through the film about Harry Smith [Harry Smith at the Breslin Hotel, 2017]. A few years ago, Robert designated MoMA as the holder of his film archive, so they will continue this initiative.

Robert was suspect that there was interest in his films. He was almost bemused, I’d even say. I would fill him in about screenings in different places in the world, and he would say, “Really? People are interested?” He started making films with people around him—not just the Beats, but also David Amram and so many denizens of the New York independent scene. [Curator] Philip Brookman had this phrase about Robert’s films: “in the margins of fiction.” That’s something that we all have seen these days, and Robert was working in that style from an early moment. I like a late film, Paper Route [2002], that he made in Nova Scotia, about this guy who delivers newspapers in an incredibly isolated place. Robert rides with him from the latest morning hours through daylight. He’s just so interested in this character. His curiosity about people was just boundless.

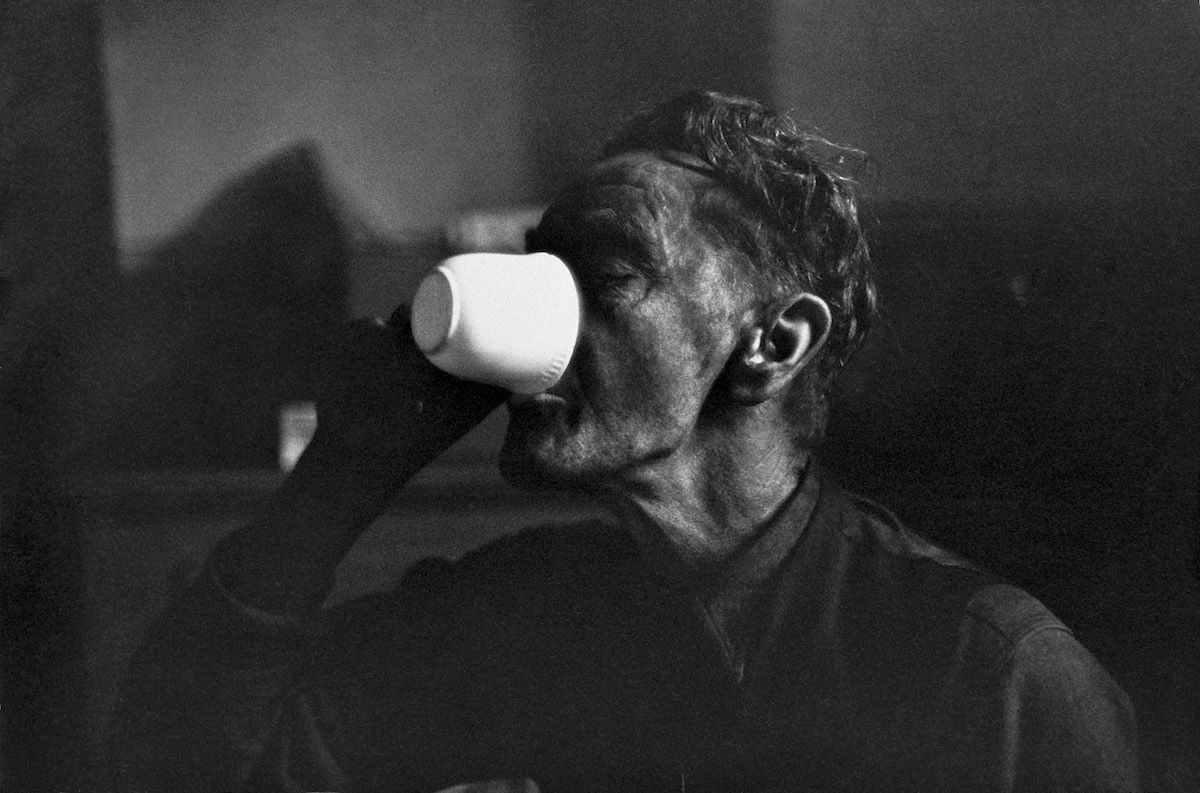

Robert Frank, View from hotel window – Butte, Montana, 1956.

©ROBERT FRANK/COURTESY PACE/MACGILL

Paul Graham

Artist

I first saw Robert Frank’s work in Creative Camera, a legendary magazine that ran for 20 years in England. It had no advertising, no technical reviews. Believe it or not, during the 1970s and early 1980s, it also had an erratic column by Robert in there, “Letter from America,” which no one really talks about. It was about the world in America—it wasn’t praising this photographer or that photographer. It wasn’t that great, but I don’t know, it had an impact on me!

Magnum wouldn’t accept him, and that intrigued me. I realized there was so much more depth to the work than there appeared at first glance. It wasn’t documentary, and I object to the New York Times headline that called him a “legendary documentary photographer.” He was so much more than that. We just shouldn’t silo him in that way, because he granted us a freedom, as artists, to be not constrained to a story, an editorial brief, or a narrative arc. That was all broken by him, even through a blurry, off-kilter picture of a cowboy looking at a jukebox. You can take a snapshot out a window where the curtain is still showing. You can photograph the hitchhiker next to you who’s driving the car. It was this liberation of photography from the straitjacket of old-school documentary visuals. In Robert’s work, there was a crystal-clear definition that life was loose and baggy and didn’t make sense, and it was irredeemably ugly. He didn’t shy away from any of that.

Peter MacGill

Cofounder of Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York

I’ve represented Robert for 36 years [since Pace/MacGill gallery was founded], plus a decade before that. He was a challenging, uncompromising, loyal friend. He got out of the box making forward-looking, never-done-before pictures. He was rejected by Magnum, and he didn’t go well with Life magazine. He set out to travel across the U.S., and he changed what photography was and how it could be done.

He expanded the possibilities of visual expression with The Americans. I think he may also go down as a great filmmaker. Half his films are at the Museum of Modern Art—they know he’s the godfather of independent film. It was extraordinary to get close to him. He was kind to me, but then he was the biggest son of a bitch on earth [to others]. It was my total privilege to work with him.

Robert Frank, Trolley – New Orleans, 1955.

©ROBERT FRANK/COURTESY PACE/MACGILL

Sarah Meister

Photography curator, Museum of Modern Art, New York

The first collection display for which I was responsible included a work from The Americans, a photograph of [Frank’s wife and son] Mary and Pablo on U.S. 90 en route to Del Rio. That picture in particular pointed to how Frank could make a picture from this incredibly personal place. He demonstrated this again and again. There’s no sentimentality, and it’s free of the problems that typically plague photographers when they make pictures of their family. Throughout his work, there’s that notion of taking what matters most to you, and making art out of it, whether that’s family or an issue of justice, or even a curiosity of how to operate in an unfamiliar territory. His influence is so vast because his interests are so vast. What unites them is this underlying commitment to authenticity. It suggested so many paths forward.

Danny Lyon

Artist

In 1961, Hugh Edwards, then the associate curator of prints and drawings at the Art Institute of Chicago told me to “go downstairs and look at those pictures” in Robert’s first one-person show in America. The prints hung on both sides of a long narrow basement corridor of the museum. Mr. Edwards also told me to go to Whittenburn and Co. on Madison Avenue to find the book [The Americans]. I bought the last two copies—the French edition, which was full of text, and the Grove Press edition [for American audiences]. Each cost $7. Edwards was crazy about Robert and visited the family when they lived downtown on East 10th Street, and he also showed many of the Magnum photographers, then the only other game in town.

Robert, like Walker Evans before him, simply exploded the medium of photography and its viewers’ relationship to reality. He showed you didn’t have to do “stories,” something I always thought was a literary term and didn’t apply to pictures. And he showed you could do it all in a book, your own book, for which you edited and sequenced the pictures. I was introduced to the Franks at a Park Place Artist’s event at Judson Church in the Village in 1967 and for two years I worked for Robert, taking audio for three of his early films. He was unusually generous for a photographer, a famously self-centered group. I learned to shoot and edit films at his knee, and was eventually replaced by Danny Seymour, with whom he did the same thing. Later, the writer and filmmaker Gary Leon Hill was in the same role, until he too was “kicked out of the next.” In his quiet way, Robert was training and then disowning his own replacements. A remarkable man, his long and amazing journey is done.

[ad_2]

Source link