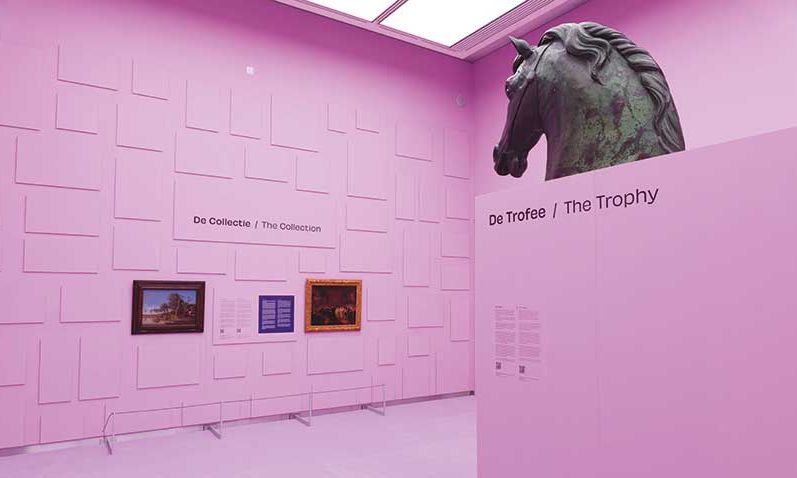

In the Mauritshuis’s show, Loot—10 Stories, the 67 missing works are represented by spaces on the walls

Photo: Ivo Hoekstra, Mauritshuis

This is a story of art looted by a European power, but one you might not expect. A new exhibition in The Hague has revealed that the Dutch are still missing 67 paintings looted by the French in Napoleonic times.

“In 1774, William V opened the first museum in the Netherlands,” says Martine Gosselink, the director of the Mauritshuis, which opened Loot—10 Stories on 14 September (until 7 January). “It was a beautiful collection of 194 paintings but in 1795, the French came into the Netherlands and took the whole collection away to Paris.”

In 1795 the Dutch Republic was transformed by the French into a vassal state, the Batavian Republic. William fled to England and his paintings were taken to France, alongside looted art from other conquered countries. Some of the Dutch collection was put on display at the Louvre in Paris. The rest was distributed to France’s new regional museums, says Quentin Buvelot, a senior curator at the Mauritshuis.

Napoleon’s defeat at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815 led to an attempt by European countries to retrieve their looted art. “Part of the negotiations were that all of the art in Paris, not the rest of France, was to be returned,” Buvelot says. However, 67 pieces of Dutch and Flemish art “had already been moved” to the regions, Buvelot adds, “and indeed, these were not returned”.

Beatrice de Graaf, a history professor at Utrecht University and the author of Fighting Terror After Napoleon: How Europe Became Secure after 1815, says that Vivant Denon, the first director of the Louvre, had tasked Napoleon’s generals with looting specific works, including vast amounts of Egyptian antiquities during an unsuccessful military campaign in Egypt. But when Napoleon was defeated in 1815, representatives from the looted countries went to Paris with lists of the works they wanted back.

“The French authorities said [the works] had disappeared,” De Graaf says. The looted countries insisted that “the French had to give back all their artwork, otherwise they would stay and keep the country occupied by their armies”. This they did, occupying two-thirds of French territory for four years, demanding reparations and the return of their art. “Some of it came back,” De Graaf says, “but not all of it.”

French archivists had written “STAT” on the back of the 194 Dutch paintings (a misspelling of the Dutch word for ruler, stadhouder). These included Rembrandt’s Simeon’s Song of Praise (1631) and Paulus Potter’s The Bull (1647), as well as works by Van Dyck, Holbein, Rubens and Jan Steen. There was a plot to hide ladders at the Louvre to stop the Dutch from recouping their works, Buvelot says, but they succeeded in salvaging the items.

By 1818, the Louvre paintings were back in the Netherlands and have been on public display at the Mauritshuis since the museum first opened in 1822. The Dutch gave up an official attempt to recover the remaining 67 works in France, such as Jan Mijtens’s The Marriage of Friedrich Wilhelm, Elector of Brandenburg with Louise Henriette of Orange in 1646, which is being borrowed for Loot—10 Stories from the Musée des beaux-arts in Rennes.

“One of the big questions that hangs over our heads in this exhibition is: do we want the works back? We are giving back colonial looted art, so why not this?” Gosselink says. On the other hand, she counters, “Do we really need them? Do we have empty depots or museums? The answer is no.”

De Graaf points out one silver lining to the French looting—public eduction. “The idea among the French occupiers was that this art in Flanders, in some dark German dungeon or in a Dutch castle, just lies there and rots away. But we, the French, our great nation, will show how art really needs to be prepared [for the public].”

However, it was only when works by Rubens, Van Dyck, Van Eyck and Breughel returned to the Netherlands that “they really became famous, and they were indeed not taken back to the castles—they were put on display in museums”, De Graaf says. “So the fact that the French looted the artwork was terrible, an act of war, but it sparked this public education campaign, both in France but also in other countries. There is something to be said for it.”

• Loot—10 Stories, 14 September-7 January 2024, Mauritshuis, The Hague; then travels to the Humboldt Forum, Berlin, in spring 2024