[ad_1]

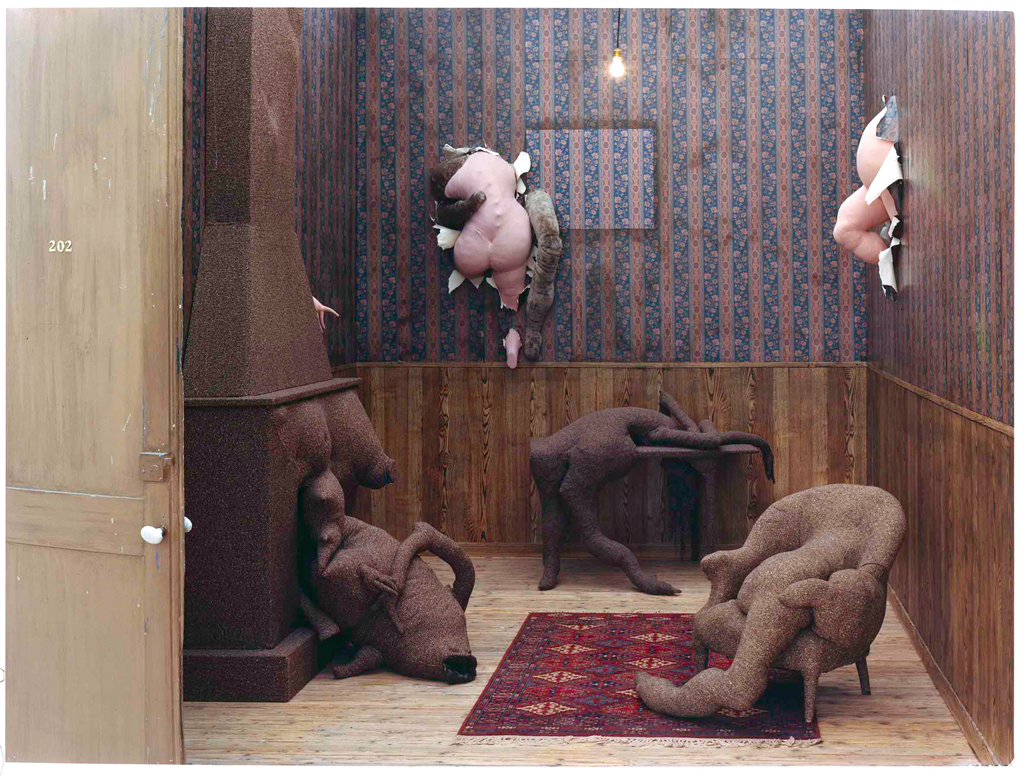

Dorothea Tanning, Chambre 202, Hôtel du Payot, 1970–73.

CENTRE POMPIDOU, PARIS

With a retrospective for Dorothea Tanning now on view at Tate Modern in London, we’ve collected excerpts of profiles of the artist and reviews of her work from past issues of ARTnews. As far as the magazine’s archives go, Tanning is a rarity—she was one of the few female artists whose work was reviewed somewhat regularly, and one of a handful whose early shows received positive notices. (One review of her first major New York show called her “one of our most skillful American Surrealists.”) The excerpts below follow Tanning as she moves from Surrealist tableaux to soft sculptures, from abstractions to poetry, and as she reflects on her long career. —Alex Greenberger

April 15–30, 1944

Dorothea Tanning, whose individual canvases have marked her as one of our most skillful American Surrealists, now gives us a chance to find out what she really has to say in a full-length show at Julien Levy’s. About a quarter of her pictures are of the purposely outrageous “game” type which is beginning to seem rather vieux jeu. The rest are more deeply felt and pondered and several are extremely moving and beautiful, especially the portrait of Deirdre with her pearly skin and prickly evergreen tresses glimpsed through a silvery haze. Here, as in Sirene and the ravishing little American Landscape, Miss Tanning proves to be an exceptionally competent painter over and above her power to induce strange dreams. It is to be hoped that she will pursue the line of original invention that makes so notable pictures like Angelic Pleasures and The Profanation, setting her well apart from the run of Surrealism’s imitators. (Prices $50 to $500.)

—“The Passing Shows”

February 1953

Dorothea Tanning [Iolas; to Feb. 6], after five years away from Fifty-Seventh Street, appears with a selection of recent works in oil and pencil. Her obsessions with adolescence and sexual fantasy are more fantastic than surreal. But she is not backward about using device which started with the Surrealists—e.g., the clipped-out negative figure of a positive image appearing elsewhere in the picture. When the idea is good, the picture looks well painted. When it is obvious (like the super-image of the father in Family Portrait, or the Johnny Ray weepings of Juke Box, the painting is thin. The pictures which resemble movie sets—the drapery-framed room with adolescents or Musical Chairs, with its drapery swirling into an orifice—are not new ideas but they look personal. Much better, and better painted are the pictures of her Lhasa terrier and the series of pictures about flowers. Some Roses and their Phantoms in which the table top is the top o the world and the roses its implacably prying inhabitants, like ants, is particularly alarming a pleasant way. $400-$2,500.

—“Reviews and previews,” by Larry Campbell

Dorothea Tanning, A Mrs. Radcliffe Called Today, 1944.

PRIVATE COLLECTION

March 1955

Within erotic Surrealism the contribution of women is distinctive. Nobody would confuse the imagery of Hans Bellmer and Leonor Fini or Delvaux and Dorothea Tanning, the wife of Max Ernst. As Valentine Penrose wrote in her Sapphic poem Dons des Féminines: “Water the hour the planet and all things feminine.” In the new paintings of Dorothea Tanning at Arthur Jeffries’ gallery, roses and drapery are folded according to chivalric and Freudian rule, a Pre-Raphaelite Io plays the piano on Sunday, and the sweet claustrophobia of her design is like a house with too many pets in it.

It has been said that the Surrealists who relied on automatism are wearing better than those who painted illustrations of the world-upside-down, but Europe has a big interest in artists with the knack of making arresting images. Dorothea Tanning’s pictures of a dog made monstrous by its owner’s desire or a girl lifted into the air by a visiting uncle (Death and the Maiden) reveal this gift. Her paint film has a thin shimmering brilliance, like an evening gown.

—“Art news from London,” by Lawrence Alloway

March 1988

Since 1980, Tanning has quietly established a life for herself—A life that is as secretively active as it was when she was a young woman making her way in New York in the ’30s. Only now her activities are more interior, for Tanning, though hardly a recluse, has curtailed her contact with New York’s hectic art scene as well as its social life. It is only as a painter that Tanning is in full swing. She works constantly on her large and small canvases, her drawings, and her watercolors.

“My life now is quiet and serene,” she says. “I have a few nice friends. I go out very little. I hardly ever go to a museum or an art opening. Frankly, I don’t know what’s going on in the art world. I’m just here in my bubble, and I stay in it. Mostly, I work.”

—“Among the Sacred Monsters,” by John Gruen

Dorothea Tanning, Eine Kleine Nachtmusik (A Little Night Music), 1943, oil on canvas.

TATE, ACQUIRED WITH THE SUPPORT OF THE ART FUND AND THE AMERICAN FUND FOR THE TATE GALLERY, 1997

September 2001

Tanning offers details of the projects and people who have defined her motivated life in the recently released Between Lives: An Artist and Her Work (W.W. Norton & Company). She describes the book as an expanded version of her earlier memoir, Birthday (Lapis Press, 1987). “Birthday was a kind of love story, mostly about my life with Max Ernst, because I was mourning his loss,” says Tanning, who met the Surrealist painter in 1942, when he came to her New York studio to look at her work. She married him four years later in Beverly Hills, in a double wedding with Man Ray and Juliette Browner. “But,” she adds, “you can’t mourn someone forever, can you?” In the years after the publication of Birthday, Tanning says she realized that there were many people in her life whose stories she hadn’t shared, including Joseph Cornell, Alberto Giacometti, Jean Arp, John Cage, and André Breton. There was the time, for instance, when Marcel Duchamp painted a mustache and goatee on a dime-store reproduction of the Mona Lisa that Ernst had been given as a mock prize at a party. On another occasion, Virgil Thomson pleaded with her to jab him with an elbow whenever he dozed off during a cello concert that he was reviewing for the New York Herald Tribune. The thought that such incidents might not otherwise be recounted led Tanning to write Between Lives. “I vowed not to make it a name-dropper,” she says. “But the people deserved to be mentioned in this adventure which is my life.”

There would have been two books this year, if not for Tanning’s decision to stop the publication of her first novel, Chasm, an enigmatic tale set at a desert ranch, because she didn’t approve of Turtle Point Press’s marketing copy. She particularly disliked a description of her as “one of a small group of major women artists who worked in the Surrealist milieu,” along with references to Ernst, she says, which she felt were unnecessary. “He was part of my life for 35 years,” she explains, sitting in her lower Manhattan apartment wearing a colorful checkered sweater and pink lipstick. “But I’ve had 55 others.” Ernst died in 1976.

—“The Oldest Living Surrealist Tells (Almost) All,” by Michelle Falkenstein

Dorothea Tanning, Étreinte, 1969.

THE DESTINA FOUNDATION, NEW YORK

April 2013

Titled “Unknown but Knowable States,” this exhibition featured Dorothea Tanning’s paintings, sculptures, and works on paper from the 1960s and ’70s, when she left behind the narrative surrealism of her early career and plunged further into her unconscious. The artist, who died last year at the age of 101, belonged to the Dada and Surrealist circles of Yves Tanguy, Man Ray, and Max Ernst, her husband. While her work from the ’40s and ’50s depicted foreboding scenes of women and children confronting strange beasts or logic-defying landscapes, she devoted herself over the next two decades to imagined, dreamlike imagery, which she laid down in rippling layers of ethereal pigment. . . .

Tanning had a sense of humor, too, which is evident in her poignant soft sculptures. Traffic Sign (1970), a fake fur pole supporting a bulbous, flesh-toned fabric breast—or pregnant belly?—has all the vulnerability of her painted figures but with an extra jolt of absurdity.

—“Reviews: Dorothea Tanning at Wendi Norris Gallery, San Francisco,” by Lamar Anderson

[ad_2]

Source link