[ad_1]

Dorothea Tanning, Eine Kleine Nachtmusik,1943, oil on canvas, 16″ x 24″. Tate Modern.

©2019 DACS, LONDON/TATE, LONDON

Under the looming threat of a no-deal Brexit, the British art scene has been pondering the future. This past spring, some institutions in London were doing so by looking to the past.

“Is This Tomorrow?” at the Whitechapel Gallery, an incisive exhibition of collaborations between artists and architecture and design firms, was a riff on a landmark 1956 exhibition of a similar title and at the same venue that included important work by proto-Pop artists.

One of the finest pieces this time around, Sankofa Pavilion (2019), a sculptural installation by Kapwani Kiwanga and the architecture firm Adjaye Associates, was a prismatic structure made from lemon-yellow, cerulean, and chartreuse glass panes. Sankofa is an Ashanti word for “reaching into the past to guide you into your future,” David Adjaye writes in the show’s catalogue. As viewers entered the sculpture, their reflections shattered, then fused.

This fractured vision was reflected by artist Zineb Sedira and Farshid Moussavi Architecture’s Borders/Inclusivity (2019), a knockout installation constructed from interlocking turnstiles. To enter it was to get lost in the piece, in a way meant to evoke permanently-in-transit migrants navigating the borders of the European Union.

And then there was a dystopic Cao Fei and Mono Office installation, which dealt with new technology in China. At its center, alongside a grid of diagrams that featured obsessively indexed images sourced from social media, stood a tall metal structure tethered to the gallery floor by guy-wires, capped by the word “TOMORROW” in neon—a vision of a garish future.

Meanwhile, over at Tate Modern, a superb Dorothea Tanning retrospective connected with present (and, surely, future) controversies over sexism. Tanning attempted to create a niche for women in the boys’ club of Surrealism. The semi-chronological show focused primarily on her rich symbolism, in particular her use of enclosed spaces that appear to metamorphose before the viewer’s eyes.

In Tanning’s 1970–73 installation Chambre 202, Hôtel du Pavot, the walls of an early 20th-century hotel room burst with female bodies, rendered in soft, puffy pink fabric, and a mysterious creature emerges insect-like from a fireplace. In the work of male Surrealists, like Paul Delvaux and Salvador Dalí, bedrooms were depicted as settings for passive females; not so for Tanning, whose work explodes such spaces, giving women agency. The future was female, even back then.

Franz West, Herbert Brandl, Otto Zitko, and Heimo Zobernig, Untitled, 1988, wood, papier mâché, and paint. Tate Modern.

STEFAN ALTENBURGER PHOTOGRAPHY ZÜRICH/©ESTATE FRANZ WEST AND ARCHIV FRANZ WEST/ HAUSER & WIRTH COLLECTION, SWITZERLAND

Also at Tate: a Franz West retrospective so good, it probably produced some converts to the late Austrian’s quirky sculptures. (The show got a nice assist from British artist Sarah Lucas, who designed some of the barriers and pedestals used to display his art.) Not all of West’s work is top-notch—his early experiments with appropriated and collaged imagery from porn and advertising come off as juvenile. But it’s hard not to be seduced by his 1980s and 1990s works, most of which are lumpy plaster-covered objects that aim to bring viewers into a new understanding of the objects underneath.

West was big on collaboration, producing these pieces with artist-colleagues like Heimo Zobernig and Gunther Förg. In rendering unfamiliar such household objects as sofas, rugs, and mirrors and elevating them to the status of sculpture, West broke down distinctions between high art and pop culture, anticipating the world we live in today.

Across town, Anthea Hamilton took up West’s themes at a Thomas Dane Gallery show in which she also made use of furniture, in her case as a response to the corporatization of modernist design. In place of wall paneling was a grid of monochromes, each formed from fluffy fabric—hard, unbending modernism rendered comfy. In another room, a low couch took the form of algorithmically arranged white cubes. Could the whole modernist project have been . . . preprogrammed? You could call that cynical, but it was also weird, kinky, and thrilling.

The cynicism continued a few blocks away, at Stephen Friedman Gallery, where Wayne Gonzales’s paintings took iconic American modernist photographs and drained them of sentimentality. In one, he has rendered the composition of an iconic Walker Evans picture of junked cars using a series of small brown “X”s, creating a crosshatched image that cohered only when looked at from a distance. Gonzales is a bit self-serious with these works, but the point is well-taken: we need to step back from this version of America if we really want to see it.

Mandy El-Sayegh, Figured Ground (detail), 2019, silkscreened ink, the Financial Times, wallpaper paste, latex, 23′ 3⅛” x 60′ ½”. Chisenhale Gallery.

COMMISSIONED AND PRODUCED BY CHISENHALE GALLERY, LONDON. ANDY KEATE/COURTESY THE ARTIST

Were there headlines about Theresa May? Yes, they were visible in dense installations and paintings by Mandy El-Sayegh at Chisenhale Gallery. El-Sayegh’s work, much of which is made from collected newspaper bits, is all about invisible networks—the ways that, say, Brexit, the history of abstraction in art, and the oppression of minority groups might all be related. A group of makeshift vitrines was filled with cutout advertisements, blobby abstract objects, and ready-made materials, including books on genetics. The title of her show, “Cite Your Sources,” conjured fake news in all its insidiousness.

If we continue consuming at our current rate, will there even be a future? At the Institute of Contemporary Arts, London were young Scottish artist Morag Keil’s ramshackle sculptures and video installations incorporating things like discarded seats from the London Tube and backpacks stuffed with dirty Starbucks cups.

Keil isn’t exactly charting new territory here—between Pop and today’s so-called post-internet artists, consumerism is well-trodden—but her commitment to her own nihilism is impressive. The best work in the show was Shopping (2019), a sound installation composed of audio sourced from commercials, YouTube videos, and the arcade game Tekken. Speakers placed in plastic bowls hung from the ceiling, as did a tangle of wiring. Media saturation makes for a hard hangover.

Installation view of “Morag Keil: Moarg Kiel,” 2019, at ICA, London.

MARK BLOWER

But consumerism’s effects may be nothing compared to those of extreme income inequality—the subject, implicitly, of Buck Ellison’s photographs of the super-rich, on view at the Sunday Painter gallery. If Keil traffics in dysfunction and a collection of crud, Ellison’s aesthetic is all slickness and order. The lily-white children in his new photographs seem immune to danger. In one large-format image, a young gymnast wearing an American flag leotard does the splits across a cannon pointed at the camera. But it’s Ellison’s lush still lifes that really strike a chord. For one, Untitled (Shares), 2016, he shot a section of a blank stock form, set to funnel money into accounts of the one-percenters.

Privilege and power—in particular, patriarchal structures in the digital sphere—were also the subjects of two new videos by Ed Fornieles at Carlos/Ishikawa gallery. For his two-channel video installation Cel (2019), Fornieles got a group of actors (including himself) to debase themselves via military-style exercises. The Live Action Role Players, or LARPers, as they’re known online, divide themselves into dominant and submissive roles, with the former always being filled by white men, one of whom stages a shooting. Fornieles lays bare the way that online aggression bleeds offline, informing real-life acts. The LARPers are reminded, “You must always have someone lower than you.”

Augustas Serapinas, February 13th, 2019, snowmen and snow from Lithuania, dimensions variable, installation view. Emalin.

PLASTIQUES/COURTESY THE ARTIST AND EMALIN, LONDON

Mindful of the constant threat of global warming and climate change, a few artists looked toward a future in which biology will have been dramatically altered. The centerpiece of Augustas Serapinas’s bizarre Emalin outing was an installation called February 13th (2019), for which the young Lithuanian artist collected pieces of snowmen he found on children’s playgrounds in Vilnius, and put them in a climate-controlled truck bound for London.

At Emalin’s main space, temporarily transformed into a walk-in freezer, these scuffed masses of snow and ice were strewn around the floor and leaned against walls like severed limbs in a serial killer’s lair. In a future where nature can be controlled by humankind, there are things that will not disappear, but instead live on in another form.

At Gasworks, Pedro Neves Marques pondered the ways in which bodies are altered by oppressive governments. A breakout of the Zika virus in 2016 formed the basis of his two-screen film installation A Mordida (The Bite), 2019, which features creepy footage of scientists synthesizing new species of mosquitos to combat infected ones.

With droning music by HAUT, it sometimes felt like an experimental horror movie, and in a way it was one: Neves Marques uses the Zika inquiry as a window into the oppression of LGBTQ+ communities in Brazil and the inability of language truly to destroy gender binaries. At one point, a technician examines his genetically altered materials and tells Neves Marques, “We control the reproduction of females.” Systemic inequities are the real horrors, and they exist both inside and far beyond the human body.

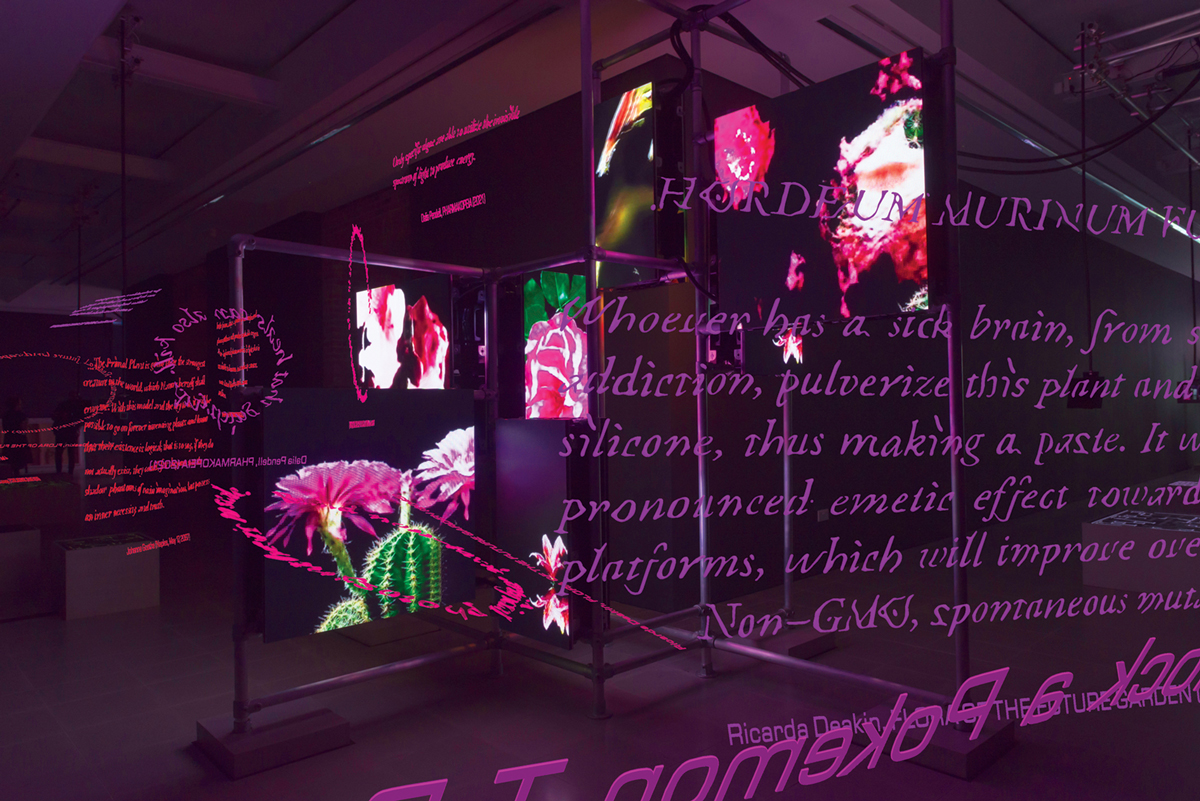

Installation view of “Hito Steyerl: Power Plants,” 2019, overlaid with the AR work Power PlantsOS, at Serpentine Sackler Gallery.

PHOTO: ©2019 READSREADS.INFO; ART: COURTESY THE ARTIST, ANDREW KREPS GALLERY, NEW YORK, AND ESTHER SCHIPPER GALLERY, BERLIN

For now, nature can’t be completely tamed, if Hito Steyerl’s Serpentine Sackler Gallery exhibition stands as any proof. In a newly commissioned installation called Power Plants (2019), Steyerl enlisted artificial intelligence to create images of flowers blooming. The results were meant to envision their growth just 0.04 seconds in the future, but the AI she used couldn’t get it quite right. As a result, the images, shown on a series of screens, rippled like molten lava or blurred like bad photography.

The screens were set in formations that resembled gardens where all the vines was replaced by cords and monitor stands. Throughout one section, an echoing voice intoned, “Is this the future?” Steyerl also showed an augmented reality piece, viewable on tablets suspended from the ceiling, that delivered faux transmissions from the near future, by such writers as art critic Jonathan Jones and anonymous Yelp reviewers. (“Serious shite, man,” the Yelp user writes of Steyerl’s Serpentine show in a review dated Summer 2019.)

This standout show felt like something truly new, both for Steyerl, whose work typically takes the form of academically minded essay films, and for artists in general, who often use AI to more fetishistic ends. Steyerl used it as a metaphor for our current fascination with predicting the digital future, even as we’re barely equipped to deal with the analog present. In a series of videos, Steyerl shot men and women ambling around the Kensington Gardens park that surrounds the Serpentine Galleries, and overlaid audio of them discussing various societal woes that have yet to be properly dealt with. “The government will say, ‘We’re giving more and more each year,’ ” one disabled woman complains, “but that’s not true—that’s not the reality.” Nevertheless, she says, “We will fight on.”

A version of this story originally appeared in the Summer 2019 issue of ARTnews on page 98 under the title “Around London.”

[ad_2]

Source link