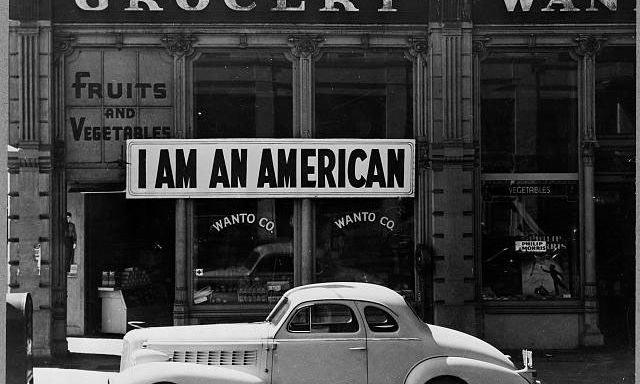

Dorothea Lange’s photograph Japanese American-Owned Grocery Store, Oakland, California (1942)

Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington

The American photographer Dorothea Lange (1895-1965) is regarded as one of the great documentary photographers of the 20th century, but a new exhibition at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, makes the case that her revolutionary style of reportage was rooted in her early experiences making formal portraits in commercial photography studios during the 1910s and 20s. Dorothea Lange: Seeing People, curated by Philip Brookman, brings together 101 of Lange’s photographs spanning half a century, from early studio portraits to images from her wide-ranging travels in the 1950s and 60s.

“She apprenticed with a series of portrait studios,” Brookman says. “Probably the best known would be Arnold Genthe’s studio in New York, and it was there she learned not only how to run a portrait studio, but also the importance of a pose—the hands, the face, the light—and how to embody who somebody is through how you pose them, how they’re lit. When she then went out into the world, and began to photograph people, she took all that with her.”

Lange's Human Erosion in California (Migrant Mother) (1936)

The exhibition draws heavily on a 2017 gift of 143 gelatin silver prints from the Los Angeles collectors Daniel Greenberg and Susan Steinhauser. These are supplemented with key loans from institutions including the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, the Oakland Museum of California and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Many of Lange’s most famous images will be on show, including her 1936 image of a white plantation owner and five Black field hands in Mississippi, and her indelible portrait of a California agricultural worker framed by her young children, Migrant Mother (1936), which Lange made while working for the US government’s Resettlement Administration. But there are also many images that are rarely shown—and some that push the boundaries of the portraiture theme, like her 1942 image of an “I am an American” sign that a Japanese American store owner put in his window amid rising xenophobia following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour.

“I really wanted to think about the notion of portraiture as something that has to do with the formation of identity and I saw those words, ‘I am an American’, as being a statement of identity that one could consider to be a portrait—this is who I am—even though it’s not a picture of a person,” Brookman says. “It’s a much more contemporary way to think about portraiture.”

Lange's Hand of Dancer, Java, Indonesia (1958) © The Dorothea Lange Collection, Oakland Museum of California, City of Oakland. Gift of Paul S. Taylor

The show gives a snapshot of Lange’s life and times, from the poverty and activism in the Bay Area in the early 1930s to the plight of agricultural workers during the Great Depression and the forced detention of people of Japanese descent during the Second World War. “The issues that she was engaged with—migration and climate change, land use, racism—all of those things are still with us today,” Brookman says. “She defined a form of documentary looking that has to do with wanting to understand not just who a person is and what they look like, but what’s around them and how their situation came to be what it is.”

• Dorothea Lange: Seeing People, National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, 5 November-31 March 2024