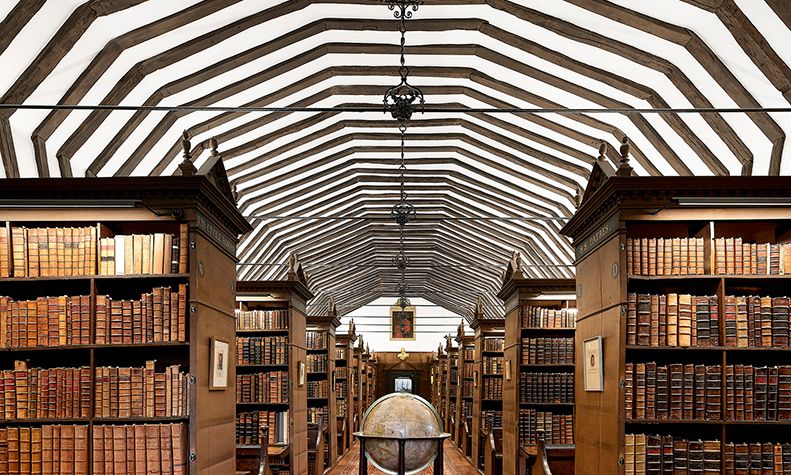

The 10-year restoration project included renovating the Old Library

© Hufton+Crow

When the wealthiest students arrived at St John’s College Oxford 400 years ago, they didn’t just hang up the 17th-century equivalent of a Wet Leg tour poster. Among the discoveries during a ten-year conservation project at the college is the revelation that some of the university’s more privileged students brought their own wooden panelling to insulate their chilly rooms—and commissioned costly wall paintings as decoration.

Other unexpected finds included cow bones in a long disused corridor. “It seems the cows were literally walked to the kitchen door, only some of them didn’t make it,” says the architect Sandy Wright, a founding partner at Wright and Wright. A signature of one Christopher Wren scratched into a window initially caused great excitement among the architects, until it was realised that it was too early to be their great predecessor; it turned out to be that of his father, a former college librarian.

The firm has just completed the final £9.2m phase of a decade-long restoration at the college, which began with a modest request to have a look at the state of the Old (1599) and Laudian (1633) libraries. Their condition turned out to be “interesting”, in Wright’s words. There were so many rare and precious books kept off access that there was hardly any space for students, and the lighting was, in any case, mostly too dim to read by. Windows were broken, floors decaying, and the pipes for the leaking heating system had been punched straight through some of the oldest bookcases in Oxford. The fire escapes were also interesting, accessed through hatches in the floor. Wright and Wright’s beautiful new library was built in 2019 when the then college president Margaret Snowling nobly suggested it could be sited on the side of her own college garden, solving the space issue. The rediscovery of the cattle-bones corridor, which had become a books and junk store, restored the link between the new buildings and the heart of the college.

The beauty of the old libraries was renewed in a comprehensive programme. New lighting and heating were installed, the cracked stained glass and leaded windows gained secondary glazing, the woodwork was replaced on the most mangled bookcases. Touches of real gold were added to Archbishop William Laud’s battered carved mitre on a tie beam and the entire floor was replaced with new broad English oak boards, held down with rose-headed nails made only in the US. The rooms under the library, crudely converted into study spaces in the 1970s with suspended ceilings and cheap modern bookshelves, have been restored as tuition rooms.

Centuries-old painted murals were found hidden beneath the plaster at Canterbury Quad

© Hufton+Crow

One of the many surprises was the rediscovery of the wall paintings. The best survivor, originally executed in expensive pigments including orpiment, an elegant flower tracery over a fine stone fireplace, is now on display again after centuries. The work on the “17th-century feature wall” in the words of Debbie Russell of Cliveden Conservation, involved stabilising, cleaning and delicately touching in paint losses. It was, she says, “a terrifying job—every centimetre of the paint was lifting and flaking. The work on just that one single painting took months”.

The glory of St John’s was—and remains—the spectacular Canterbury Quad, the gift of Laud, a serial political meddler under Charles I, who made him Archbishop of Canterbury. Bronze effigies of Charles and his queen, Henrietta Maria, look down from among its spectacular stone carvings. They came to the college for the formal opening of the new space in 1635, marked by a week-long party that reputedly cost more than the building itself. Royalist forces would return to occupy the college when the Court fled to Oxford in the Civil War and Laud was executed by Parliament at the Tower of London in 1645, to be buried in the college chapel.

The upper floors around the quad are supported by elegant pairs of stone columns, which the architects initially believed needed only minor repairs. As the work was about to go to tender, it was realised that the cracks had dramatically worsened in one column. After a complete survey, the drastic decision was made, in agreement with Historic England and local planners, to replace all of them. Some proved to be century-old replacements in Portland stone, but the oldest were Bletchingdon marble, which is no longer mined. With the aid of stone expert Dr David Jefferson, Swaledale fossil, a fossil-rich limestone, was chosen. There were more moments of terror as the arcade was propped to remove the old columns and insert the gleaming, polished new ones, although college closures during the Covid-19 pandemic meant that at least the students were out of the way. The new columns are expected to last better than the originals; the stone workers say that the next condition check should be due in 2407.

Wright sings the praises of the builders, carpenters, masons, and paint, stone and timber conservation experts who have worked together throughout the whole process: “It’s been quite a journey.”

• The historic quads, chapel and gardens of St John’s are open in the afternoons to visitors: www.sjc.ox.ac.uk