[ad_1]

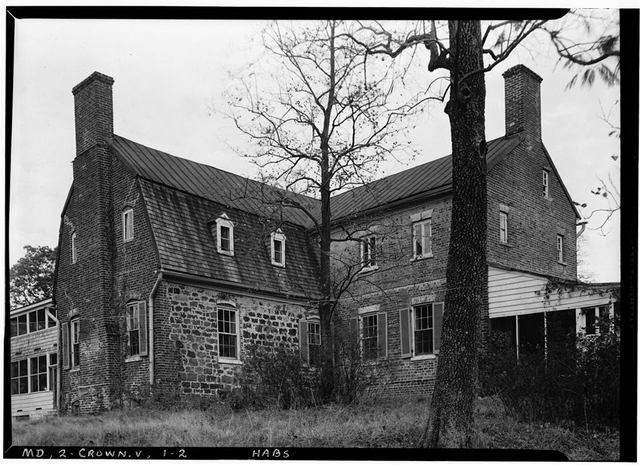

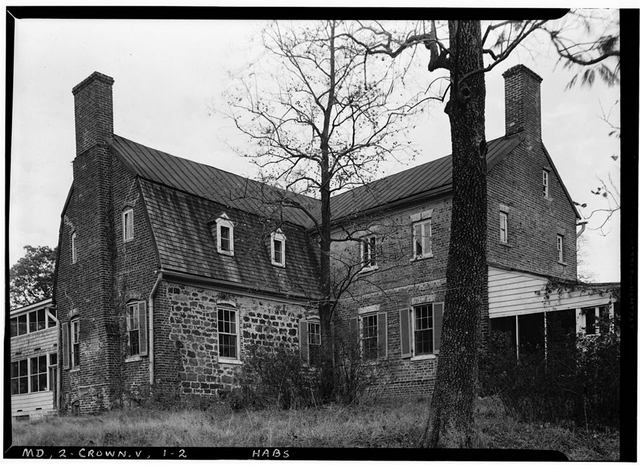

CROWNSVILLE, Md. (AP) — Two years ago archaeologists uncovered and examined unique stone slave quarters on what was the Belvoir Plantation in Crownsville. Now they think they have found the resting place for some of those who died in bondage there.

It might not have come were it not for a tip from a local resident who used to live and work on the property nearly 50 years ago.

“I got this call from Rodney Daff who said, ‘We think we know where the slave burial ground is,’” said Julie Schablitsky, chief archaeologist for the Maryland State Highway Administration.

“People call all the time saying they have found all these great things. But Rodney took me straight to it.”

Rodney recalled seeing the spot when his family served as caretakers on the property and worked a huge strawberry farm in the 1970s.

After a little work with a leaf blower on a small promontory in the woods on what remains of the once grand plantation, now owned by a Rockbridge Academy housed in the old plantation house, the evidence emerged.

Small stones peeping through the forest floor, two slabs of marble that were likely a gravestone before being broken, and a significant indentation in the ground facing west to east – the common burial practice.

Studying the site closer to the stones, some mere nubs of well worn rock, another an obvious slab cracked off just above the ground, lined up in a row. Another smaller line emerged.

Another sign the area was of significance are 10 or more cedar trees circling the promontory, now nothing but gnarled and shredded stumps, the tallest about 3 feet.

“With all these multiples of evidence… we are scientists, we want proof.”

Along with Anne Arundel County’s archaeologist, Jane Cox, a group including descendants of slaves who lived at Belvoir returned to the site two weeks ago.

Three cadaver scenting dogs from Bay Area Recovery Canines in Annapolis, who usually work at disaster sites to find people buried in rubble, were brought to the site.

One at a time, the dogs circled the perimeter then worked their way toward the middle. All three stopped and laid down at the same spot – the indentation – their signal they have sniffed human decomposition. They signaled at other spots too.

“You had to have been there,” said Wanda Watts, a descendant of Belvoir slaves. “To me it was the most exciting thing other than the birth of my son.”

“This does not happen for African Americans. Our names were changed, we were scattered,” she said. “African Americans know little of their history, we can only go back one, two, or three generations.”

Another descendant, Nancy Daniels, was emotional. “When the dogs did that I said, ‘I am not going to cry, I am not going to cry.’ I was overwhelmed with happiness that they were able to find them.”

She knows her people lived there through her genealogical research, which she teaches. “I have the manumission papers that Thomas Burley, my great-great-great-great-grandfather, signed to free his wife and daughter and her five children.”

On March 4, 1854, Burley, a free man who worked at a glass factory in Frederick, filed the papers setting them free. He had saved money and bought the freedom for his wife Anne, and daughter, Ellen, a few years earlier from plantation owner George Worthington. That made Burley their owner until he filed the manumission.

No one knows whether any of her or Watts’ descendants are buried there. And they may never know unless agreements are made and funding is secured to return for further exploration.

Cox and Schablitsky both noted different ways to learn more about who is buried at the site.

“There is some testing that can be done without removing any bones. We can learn from coffin hardware when they were buried. We can look at the bones to see their age, sex, any signs of disease.” They could also take seeds found in the grave to determine what kind of flowers were put in the grave.

Schablitsky said it is also possible to make connections through DNA science.

“If we can take a small piece of bone or a tooth, we can send it to a lab and possibly connect it to a living descendant,” she said.

But that’s getting ahead of things.

There are no plans to do any further excavation, Schablitsky said. “We are happy with this discovery right now.”

But for those whose forbearers toiled in bondage on this land the discovery brings more hope.

Daniels was moved to fill a plastic vial of earth from the site during a visit Friday. “I hope to get more. I will put it in my garden,” she said.

Watts, who through a lot of work and luck, knows her family was at Belvoir in the 18th Century, was quiet.

“There is a feeling of peace now, knowing they were not just tossed away. There was some reverence – they were people.”

___

Information from: The Capital, http://www.capitalgazette.com/

[ad_2]

Source link